David Paul Fernandez, Eugene Y. J. Tee & Elaine Frances Fernandez

Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity

The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, Volume 24, 2017 – Issue 3

Abstract

The present study aimed to explore whether scores on the Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 (CPUI-9) are reflective of actual compulsivity. We examined whether CPUI-9 scores are predicted by failed abstinence attempts and failed abstinence attempts × abstinence effort (conceptualized as actual compulsivity), controlling for moral disapproval. A group of 76 male Internet pornography users received instructions to abstain from Internet pornography for 14 days and to monitor their failed abstinence attempts. Greater Perceived Compulsivity scores (but not Emotional Distress scores) were predicted by abstinence effort, and failed abstinence attempts when abstinence effort was high. Moral disapproval predicted Emotional Distress scores, but not Perceived Compulsivity scores. Implications of the findings are discussed.

DISCUSSION SECTION

The present study is an attempt to examine whether CPUI-9 scores are predicted by actual compulsivity in IP use. A quasi-experimental design was employed, with the introduction of abstinence effort as a manipulated variable. We sought to investigate two research questions

- RQ1: Will failed abstinence attempts predict CPUI-9 scores, controlling for abstinence effort and moral disapproval?

- RQ2: Will failed abstinence attempts interact with abstinence effort to predict CPUI-9 scores, controlling for moral disapproval?

Baseline abstinence effort, baseline frequency of IP use, baseline CPUI-9 scores, moral disapproval of pornography, and alternative sexual activity were controlled for in the present study. The Access Efforts subscale of the CPUI-9 was omitted from the analyses due to poor internal consistency.

In summary, when the CPUI-9 was taken as a whole, moral disapproval of pornography was the only significant predictor. However, when broken down into its subcomponents, moral disapproval was found to predict Emotional Distress scores, but not Perceived Compulsivity scores. Perceived Compulsivity scores were in turn predicted by abstinence effort, and by failed abstinence attempts X abstinence effort, which we conceptualize as actual compulsivity in the present study.

H1: Failed abstinence attempts on CPUI-9 scores

Our first hypothesis that failed abstinence attempts would predict higher CPUI-9 scores, controlling for abstinence effort and moral disapproval, was not supported. We did not find any significant relationship between failed abstinence attempts and any of the CPUI-9 scales. We hypothesized that failed abstinence attempts would predict CPUI-9 scores even when controlling for abstinence effort because we conjectured that the individual’s behavior itself (i.e., failed abstinence attempts) would be perceived as concrete evidence of compulsivity when given explicit instructions to abstain from viewing pornography for a 14-day period. Rather, the present study’s findings showed that failed abstinence attempts was only a significant predictor of Perceived Compulsivity scores depending on the degree of abstinence effort exerted, which was our second hypothesis in this study.

H2: Failed abstinence attempts X abstinence effort on CPUI-9 scores

We found partial support for our second hypothesis, that failed abstinence attempts would interact with abstinence effort to predict higher CPUI-9 scores, controlling for moral disapproval. However, this relationship was limited to Perceived Compulsivity scores, and not Emotional Distress scores and CPUI-9 full scale scores. Specifically, when failed abstinence attempts are high and abstinence effort is high, higher scores on the Perceived Compulsivity subscale are predicted. This finding is consistent with our proposition that it is not merely frequency of pornography use which contributes to perceptions of compulsivity, but that this would also depend on an equally important variable, abstinence effort. Previously, studies have demonstrated that frequency of pornography use accounts for some variance in the CPUI-9 (Grubbs et al., 2015a; Grubbs et al., 2015c), but frequency of pornography use alone is not sufficient to infer the presence of compulsivity (Kor et al., 2014). The present study posits that some individuals may view IP frequently, but may not be exerting substantial effort in abstaining from IP. As such, they might have never felt that their use was compulsive in any way, because there was no intention to abstain. Accordingly, the present study’s introduction of abstinence effort as a new variable is an important contribution. As predicted, when individuals tried hard to abstain from pornography (i.e., high abstinence effort) but experienced many failures (i.e., high failed abstinence attempts), this aligned with greater scores on the Perceived Compulsivity subscale.

Abstinence effort on CPUI-9 scores

Interestingly, abstinence effort as an individual predictor also demonstrated a significant positive predictive relationship with the Perceived Compulsivity subscale (but not the Emotional Distress subscale and the CPUI-9 full scale), controlling for failed abstinence attempts and moral disapproval, although this relationship was not hypothesized a priori. We predicted in the present study that only individuals who actually experienced failed abstinence attempts might infer compulsivity from their own behavior, leading to perceptions of compulsivity. However, we found that greater abstinence effort predicted higher scores on the Perceived Compulsivity subscale, and that this relationship was seen even independent of failed abstinence attempts. This finding has the important implication that trying to abstain from pornography in and of itself is related to perceptions of compulsivity in some individuals.

We consider two possible explanations for this phenomenon. First, although not measured in the present study, it is possible that the positive relationship betweenabstinence effort and perceived compulsivity might be mediated by the perceived difficulty or subjective discomfort that participants might have felt by merely trying to abstain from pornography, even if they did not actually fail to abstain. A construct that might describe the perceived difficulty or subjective discomfort felt while attempting to abstain would be the experience of craving for pornography. Kraus and Rosenberg (2014) define craving for pornography as “a transient but intense urge or desire that waxes and wanes over time and as a relatively stable preoccupation or inclination to use pornography” (p. 452). Craving for pornography may not necessarily need to lead to pornography consumption, especially if individuals have good coping skills and effective abstinence strategies. However, the subjective experience of desiring pornography and experiencing difficulty in keeping committed to the abstinence goal might have been enough for participants to perceive compulsivity in their IP use. It is noted that craving or urges represent a key element of theoretical addiction models (Potenza, 2006), and has been part of the proposed criteria for Hypersexual Disorder for the DSM-5 (Kafka, 2010), suggesting the possible presence of an actual addiction. Thus, craving for pornography (and related constructs) might be an important inclusion in future studies examining abstinence from pornography.

Second, we also considered that “abstinence effort” might have been counterproductive for some participants. Some participants, when exerting abstinence effort, could have made use of ineffective strategies (e.g., thought suppression; Wegner, Schneider, Carter, & White, 1987) in their attempts at self-regulation, leading to a rebound effect of IP intrusive thoughts, for instance. After a failed abstinence attempt, participants might have entered a vicious cycle of “trying even harder” to abstain, instead of making use of more effective strategies such as mindfulness and acceptance in dealing with urges (Twohig & Crosby, 2010) and self-forgiveness after a slip (Hook et al., 2015). As such, any internal experience such as thoughts or desire for IP might have been inordinately magnified, leading to greater perceived compulsivity. However, our explanations remain speculative at this point. More research is needed to understand the abstinence effort variable in relation to perceived compulsivity.

Moral disapproval on CPUI-9 scores

We found that when the CPUI-9 was taken as a whole, moral disapproval was the only significant predictor. However, when broken down, moral disapproval predicted only a specific domain of the CPUI-9, the Emotional Distress subscale (e.g., “I feel ashamed after viewing pornography online”) and had no influence on the Perceived Compulsivity subscale. This is consistent with previous research showing moral disapproval of pornography to be related only to the Emotional Distress subscale and not the Perceived Compulsivity or Access Efforts subscales (Wilt et al., 2016). This also lends support to Wilt and colleagues’ finding that moral disapproval accounts for a unique aspect of the CPUI-9, which is the emotional aspect (Emotional Distress), rather than the cognitive aspect (Perceived Compulsivity). Thus, although the Emotional Distress and Perceived Compulsivity subscales are related, our findings suggest that they need to be treated separately as they seem to be formed via different underlying psychological processes.

Theoretical implications

Our findings have three important theoretical implications. First, the present study elucidates the previously unexplored relationship between perceived addiction to IP, as measured by the CPUI-9, and actual compulsivity. In our sample, we found that perceptions of compulsivity were indeed reflective of reality. It appears that an actual compulsive pattern (failed abstinence attempts £ abstinence effort), and abstinence effort on its own, predict scores on the CPUI-9 Perceived Compulsivity subscale. We found that this relationship held even after holding moral disapproval constant. Thus, our findings suggest that regardless of whether an individual morally disapproves of pornography, the individual’s Perceived Compulsivity scores may be reflective of actual compulsivity, or the experience of difficulty in abstaining from IP. We propose that while actual compulsivity does not equate to actual addiction, compulsivity is a key component of addiction and its presence in an IP user might be an indication of actual addiction to IP. Therefore, the current study’s findings raise questions about whether research on the CPUI-9 to date can to some extent be accounted for by actual addiction, beyond mere perception of addiction.

Second, our findings cast doubts on the suitability of the inclusion of the Emotional Distress subscale as part of the CPUI-9. As consistently found across multiple studies (e.g., Grubbs et al., 2015a,c), our findings also showed that frequency of IP use had no relationship with Emotional Distress scores. More importantly, actual compulsivity as conceptualized in the present study (failed abstinence attempts £ abstinence effort) had no relationship with Emotional Distress scores. This suggests that individuals who experience actual compulsivity in their pornography use do not necessarily experience emotional distress associated with their pornography use. Rather, Emotional Distress scores were significantly predicted by moral disapproval, in line with previous studies which also found a substantial overlap between the two (Grubbs et al., 2015a; Wilt et al., 2016). This indicates that emotional distress as measured by the CPUI-9 is accounted for mainly by dissonance felt due to engaging in a behavior that one morally disapproves of, and is unrelated to actual compulsivity. As such, the inclusion of the Emotional Distress subscale as part of the CPUI-9 might skew results in such a way that it inflates the total perceived addiction scores of IP users who morally disapprove of pornography, and deflates the total perceived addiction scores of IP users who have high Perceived Compulsivity scores, but low moral disapproval of pornography. This may be because the Emotional Distress subscale was based on an original “Guilt” scale which was developed for use particularly with religious populations (Grubbs et al., 2010), and its utility with non-religious populations remains uncertain in light of subsequent findings related to this scale. “Clinically significant distress” is an important component in the diagnostic criteria proposed for Hypersexual Disorder for the DSM-5, where diagnostic criterion B states that “there is clinically significant personal distress … associated with the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors” (Kafka 2010, p. 379). It is doubtful that the Emotional Distress subscale taps into this particular sort of clinically significant distress. The way the items are phrased (i.e., “I feel ashamed/depressed/sick after viewing pornography online”) suggests that distress need not be associated with the frequency and intensity of the sexual fantasies, urges, or behavior, but could be brought about merely from engaging in the behavior even in a non-compulsive way.

Third, this study introduced abstinence effort as an important variable in relation to understanding how perceptions of compulsivity might develop. It is noted that in the literature, frequency of IP use has been investigated without taking into account participants’ varying levels of abstinence effort. The present study’s findings demonstrate that abstinence effort on its own, and when interacting with failed abstinence attempts, predicts greater perceived compulsivity. We have discussed the experience of difficulty at abstaining or craving for pornography as a possible explanation of how the abstinence effort on its own may predict greater perceived compulsivity, in that the difficulty experienced may reveal to the individual that there may be compulsivity in their pornography use. However, at present, the exact mechanism by which abstinence effort relates to perceived compulsivity remains uncertain and is an avenue for further research.

Clinical implications

Finally, our findings provide important implications for the treatment of individuals who report being addicted to Internet pornography. There has been evidence in the literature to suggest that there have been an increasing number of individuals reporting being addicted to pornography (Cavaglion, 2008, 2009; Kalman, 2008; Mitchell, Becker-Blease, & Finkelhor, 2005; Mitchell & Wells, 2007). Clinicians working with individuals who report being addicted to pornography need to take these self-perceptions seriously, instead of being skeptical about the accuracy of these self-perceptions. Our findings suggest that if an individual perceives compulsivity in their own IP use, it is likely that these perceptions might be indeed reflective of reality. In the same way, clinicians should realize that “perceived compulsivity” could be seen as a useful perception to have, if the perception is reflective of reality. Individuals who experience compulsivity in their IP use might benefit from gaining self-awareness that they are compulsive, and can use this insight into their own behavior to decide whether they need to take steps toward changing their behavior. Individuals who are unsure about whether their IP use is compulsive or not can subject themselves to a behavioral experiment such as the one employed in this study, with abstinence as the goal (for a 14-day period or otherwise). Such behavioral experiments might offer a useful way to ensure that perceptions are grounded in reality, through experiential learning.

Importantly, our findings suggest that cognitive self-evaluations of compulsivity are likely to be accurate even if the individual morally disapproves of pornography. Clinicians should not be too quick to dismiss cognitive self-evaluations of individuals who morally disapprove of pornography as overly pathological interpretations due to their moralistic beliefs. On the other hand, clinicians need to keep in mind that the emotional distress associated with pornography use experienced by clients, especially ones who morally disapprove of pornography, appears to be separate from the cognitive self-evaluation of compulsivity. Emotional distress, at least in the way it is measured by the CPUI-9, is not necessarily the result of compulsive IP use, and needs to be treated as a separate issue. Conversely, clinicians need to also be aware that an individual could be experiencing actual compulsivity in their IP use without necessarily feeling emotions such as shame or depression associated with their IP use.

Limitations and directions for future research

A limitation of the present study is that abstinence effort as a variable is new, and as a result is still a vaguely understood variable. Only a single item was used to measure abstinence effort, limiting the reliability of the measure. New self-report measures would need to be constructed to better understand its mechanisms. Further, abstinence effort was artificially induced through an experimental manipulation, and as a result, there might have been a lack of intrinsic motivation in participants to abstain from IP in the first place. Future research should also take into account motivation to abstain from IP, which is likely related to abstinence effort as a construct but surely distinct. It is possible that motivations to abstain from IP, whatever the reasons, might influence how the abstinence task is approached by participants.

A second limitation inherent in the present study’s design is that it spanned a total of 14 days. The 14-day period could be regarded as too short a period to reflect the complexities of how perceptions of compulsivity develop in individuals in a real-world setting. For example, it might be possible for some individuals to successfully abstain from pornography for 14 days, but might find it more difficult to do so for a longer period of time. It would be useful for future studies to experiment with abstinence tasks of varying durations, to determine if abstinence duration makes a difference.

A third limitation is that the sample used in the present study limits the generalizability of the findings. Participants were male, Southeast Asian, and a large majority consisted of an undergraduate psychology student population. Also, a non-clinical population was used in the present study, which means that the current study’s findings cannot be generalized to a clinical population.

Finally, there was a lack of standardization in the way baseline frequency of pornography use and failed abstinence attempts were measured in the present study, which was in terms of frequency, i.e., “how many times did you view IP in the past 14 days,” while previous research (Grubbs et al., 2015a, etc.) have measured pornography use in terms of amount of time spent (hours). Although measuring the variable in terms of hours might provide a more objective quantitative measure of pornography use, a downside of this method is that amount of time spent watching does not necessarily translate into frequency of pornography use. For example, it is possible that an individual spends three hours viewing pornography in a single sitting, and does not view pornography the other 13 days, reflecting more time spent, but low frequency. Also possible is another individual watching 10 minutes of pornography every day of the 14-day period, reflecting greater frequency but overall less time spent. We propose that a better way to measure failed abstinence attempts would be frequency and not total hours. Considering the number of times a participant views IP as discrete events might be more reflective of the way IP viewers might regard failed attempts at abstinence (i.e., after each discrete “slip” [failure], abstinence effort is reinstated, signifying the next attempt, and so on). Still, a downside of measuring pornography use in this way is that each discrete “time” a participant views pornography is arbitrary in terms of time spent. For a more complete picture, future studies can take into account both measures of IP use.

Conclusion

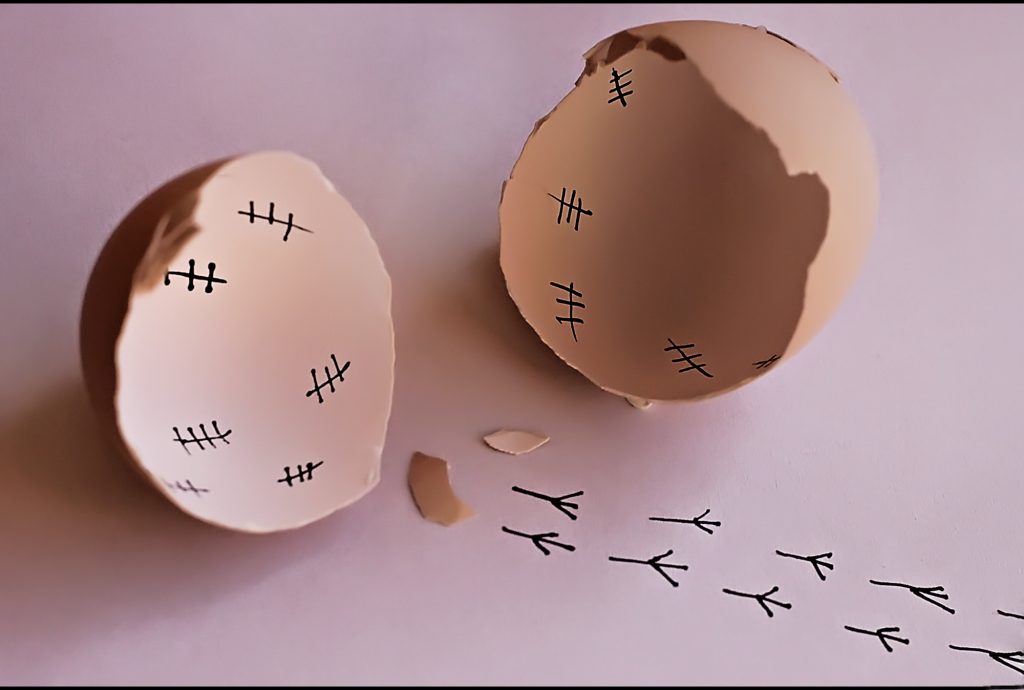

The present study was an attempt to explore whether CPUI-9 scores are reflective of actual compulsivity. In summary, we found that when the CPUI- 9 was taken as a whole, moral disapproval was the only significant predictor. However, when broken down, moral disapproval only predicted Emotional Distress scores, and not Perceived Compulsivity scores. Contrary to prediction, failed abstinence attempts did not predict any of the CPUI-9 scales. Rather, failed abstinence attempts predicted Perceived Compulsivity scores (but not Emotional Distress scores), contingent on high abstinence effort. Specifically, when abstinence effort was high and failed abstinence attempts were high, Perceived Compulsivity scores were high. We found that this relationship held even after controlling for moral disapproval, suggesting that Perceived Compulsivity scores to some extent reflect actual compulsivity, regardless of whether the individual morally disapproves of pornography. Our findings also raise questions about the suitability of the Emotional Distress subscale to be included as part of the CPUI-9, since the Emotional Distress subscale had no relationship with actual compulsivity. More broadly, our study introduces abstinence effort as an important variable that needs to be investigated further in order to better understand compulsive pornography use.