Relevant excerpt:

I’ve also helped many couples address sexual functioning problems that have arisen from being conditioned to speedy arousal and orgasm from rapidly moving visual stimulation, leaving the individual unable to get aroused or reach orgasm in their partnered sex.

——————————————-

One of my earliest memories is of sitting in the bath in our home in 1960s suburban Stokes Valley; a damp little village nestling in gorse covered hills between Upper Hutt and Lower Hutt, north of Wellington. Me, aged about 4 or 5 at one end, my older sister at the other end and our little brother in the middle. Mum standing over us, with her pinny on, shaking her finger at my brother, saying: “If you don’t stop playing with that thing and making it go hard, it will fall off!” Suddenly it occurred to me, THAT’S what must have happened to mine.

A few years later I discovered a strange, flying saucer-shaped object lying on the bathroom chair. On racing into the kitchen to report this invasion to Mum, I got told not to be stupid and indeed, when I crept down the hallway to check it again, it had disappeared.

Roll forward another few years and I’m at intermediate, watching the film about reproduction with Mum on girls’ night, followed by a long silent ride home. A year or two later my sister passed on her book about periods, produced by Johnson & Johnson, manufacturers of sanitary napkins. As a late developer, I had some time to get used to that idea and for my much longed for breasts to eventually sprout. In the fifth form, my biology teacher got his wife to teach us the single lesson about reproduction, apparently unconcerned about what he was modelling for us by his absence.

Little surprise then, surely, that when I discovered pornography I had no idea what to make of it. Mum and Dad owned a dairy for three years from when I was 14, giving me ready access month after month to Playboy and Penthouse. Arousing but simultaneously disturbing, I worried about all the ways I did NOT look like the girls in the photos and whether I was meant to act like that or not. Mum didn’t; the only makeup she ever wore was lipstick and I’d watched her undo the navy top stitching she had sewn on her newly made plain light blue dress, commenting it looked tarty. Was I meant to choose between being a good girl and a sexy girl? Equally or maybe more importantly, which did the boys want?

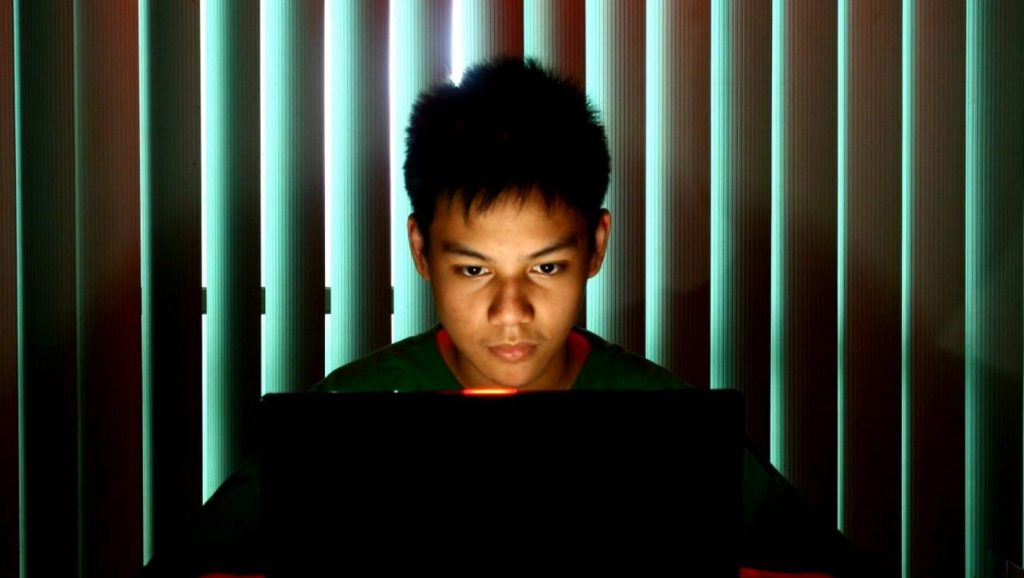

It was somewhat predictable then that my early endeavours into sex were fumbling, ill-informed and unsatisfying. Are our kids better informed now in 2020 than in the previous century? Some will be but I fear many are still not, so I was not at all surprised to see the findings released by our chief censor, David Shanks, of his office’s latest research into young people and pornography. This important study showed that, while our young people want to be able to talk to adults about what they are seeing in order to help process it, most don’t talk with their parents, given the taboo around viewing porn. Guilt and shame drive their viewing underground, for girls to an even greater extent than boys, because of the double standard they still encounter. Their dilemma is ongoing: how to be sexy yet respected.

The research also found that, because porn is so easily accessible on the myriad devices children and young people – or at least their friends – have access to, it has become normalised. Young people reported kind of knowing it’s not real sex but, even so, that it is shaping their thinking. Given the power of peer pressure, the in-depth interviews revealed that, even though they know porn sex is not real sex, it’s common for teens to act out what they’ve seen in porn because they think it’s what their partner will want or expect. They acknowledge that they are of course curious and keen to learn about sex and their sexuality, they have sex hormones zinging around their bodies, so porn also becomes both an easy arousal and masturbation aid, and a default learning tool.

Is this how we want our kids to learn about sex? Identifying and understanding their sexual preferences based on what kinds of porn activities turn them on? The answer from me and I hope the majority of our population, is a resounding no.

There is so much more to sexuality and partnered sex than can ever be portrayed by any video with a commercially based aim of stimulation. Professionally, I have seen so many couples who lack the crucial skills for intimate relating and so many individuals who feel bad about their own body or “performance” in contrast to what they have seen online. What’s more, pornography often models a detached “doing to”; using a partner, rather than caring about them. When hurtful, even abusive behaviour is reported, it has often been modelled on learning from early exposure to porn that was never picked up and dealt with effectively.

I’ve also helped many couples address sexual functioning problems that have arisen from being conditioned to speedy arousal and orgasm from rapidly moving visual stimulation, leaving the individual unable to get aroused or reach orgasm in their partnered sex. My personal view about mainstream porn is that, similar to food and alcohol, it’s not the product so much as how you use it – though there are of course some products in each of these three categories which are more life-enhancing than others. My conclusion from three decades of professional experience has to be that pornography is simply not a good teacher.

Parental discussions about porn are generally recommended to come after basic sex education, often referred to as “the sex talk”, which usually happens in the later childhood or tween years, if at all. My opinion is that not only is this far too late but that to aim for a singular “talk” is a serious underestimation of what’s required.

The best and obvious way forward is that we embed sex education from birth onwards. Curiosity about one’s own body is healthy and innate. Watch the fascination on an infant’s face as they discover that this hand turning in front of them is their own, under their control. Notice their determination if you try retrieving the flannel off them as they do a very vigorous job of washing their genitals, because they’ve discovered how good it feels. Bath time and dressing is a great opportunity to name body parts. Children who have received the parental message that their bodies and their curiosity are OK will guide parents on what they want to know. Some will express it by asking questions, others explore, some do both.

Any parent who feels awkward as they come to talk about the “private parts”, rest assured; that improves with practice. In my early counselling days I used to stutter when I had to say the words “penis” or “masturbation”. I just wasn’t used to saying such words, even as a partnered heterosexual woman with a male child! As I write this I wonder, was I any more comfortable or familiar with saying clitoris, vulva, vagina? I doubt it. Now, in some company, I’m sure those words roll off my tongue all too readily.

As they grow up there are so many opportunities to teach children about privacy, respect, pleasure and consent. These conversations don’t need to and should not wait for adolescence. That way when it’s time to talk about sexual activity the groundwork is done, the concepts are familiar and the channels of communication and skills to use them, are all well established. You’ve become a safe go-to person for any questions or concerns and the values and knowledge base for developing porn literacy is in place. There are valuable guides to discussion about porn and related tools and information on classificationoffice.govt.nz , along with detailed reports on the research on this topic.

Of course, what you model throughout your children’s growing up years will have even more impact than what you say. When you create in your whānau a culture of open discussion, sometimes you will have to hear perspectives that are very different from those you may wish to impart to your young people. But if you don’t show interest in and respect for their views, why would they listen to and consider yours? And if you condemn some of their beliefs or choices, why would they come to you when they’re confused or troubled by what they’ve seen or experienced? There are ways to express concern that avoid shaming.

Parents could be valuably aided in their work to help their children develop their sexual identity and confidence. Our schools are mandated to provide 12-15 hours of sex education per year from early childhood through until the end of secondary school. Sadly this level of education seems to be happening in very few schools, but when we do have all teachers trained and resourced to embed sexuality information into their lessons, we will be another step towards helping all young people have a clear and well-rounded understanding of some fundamental concepts. Then when they become parents they are resourced for the task. I genuinely believe that, together, we can prepare our children for whatever they will discover about sex and sexuality in their lifetime.

Reluctantly, I need to end on a cautionary note. Unprepared children exposed to porn equals sexual abuse. They may be troubled or even utterly overwhelmed by what they see, with all the consequent trauma impact and potential for the adult sexual relating problems described above. Children who are used to discussing matters of sexuality with parents are more likely to report any such exposure and get the help they need to process and resolve their reactions. Parents/whānau and other caregivers keen to protect children and young people can read a comprehensive summary of normal sexual behaviours at each age group, when to be concerned about sexual behaviours and what action to take about child sexual abuse in a book I edited entitled Free to Be Children. These were developed by international expert Toni Cavanagh Johnson.

In the process of compiling that book, in my practice as a psychologist and in my own life, the same message pops up clearly and repeatedly: openness and honesty is essential in all relationships, and especially those we have with our children and teenagers. If you make your home a safe place where kids can discuss what they’ve seen online without fear or shame, the more insidious aspects of pornography will lose their power.

Robyn Salisbury is a clinical psychologist, regular Sunday magazine columnist and editor of Free to Be Children: Preventing child sexual abuse in Aotearoa/NZ.

LINK TO ORIGINAL ARTICLE