Wright, P.J. Arch Sex Behav 50, 393–399 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01922-z

“Let it go, let it go

Can’t hold it back anymore

Let it go, let it go

Turn away and slam the door” (Elsa – Disney’s Frozen)

In another Letter in this issue, I wrote a brief exposé on the many perils of the current approach to third-variables in pornography effects research (Wright, 2021). I hope readers of this Letter will read its precursor, but its thesis is that pornography researchers should treat third-variables as predictors (i.e., factors that differentiate the frequency and type of pornography consumed), mediators (i.e., mechanisms carrying the effects of pornography), or moderators (elements of people and contexts that either inhibit or facilitate the effects of pornography),

About a decade late to the Frozen party, having had my daughter only recently at an age rivaling Abraham, I quoted Elsa in asking my colleagues to “Let go” of the “potential confound” paradigm and move into a “predictors, processes, and contingencies” paradigm. As I noted, this exhortation was a few years in the making and I felt relieved to have finally, formally, articulated it.

In the following days, however, a sense of “unfinished business” was increasingly palpable. I knew there was another lingering message in need of expression. Turning to Frozen II now for inspiration (as my daughter has moved on to Elsa and Anna’s next adventure), I quote Anna and encourage my colleagues to see the folly of her words as they are currently applied to the “selective-exposure as alternative explanation” convention in cross-sectional pornography effects research.

Problematic Current Approach

“Some things are always true; Some things never change”

(Anna – Disney’s Frozen II)

As any reader even casually familiar with the discussion sections of pornography effects papers utilizing cross-sectional data knows, it is a virtual guarantee that the authors will caution that any association they found between pornography use (X) and the belief, attitude, or behavior under study (Y) may be due to “selective-exposure” (i.e., people already in possession of the belief, attitude, or behavioral pattern gravitating to sexual media content that depicts it) not sexual socialization (i.e., people being influenced by the sexual media content in the direction of the belief, attitude, or behavior). In other words, the authors will adopt the stance that despite the pages of conceptual and theoretical arguments they devoted to justifying a X → Y dynamic in their literature review section, it is just as likely the case that Y → X. The author will then call for “longitudinal research” to “untangle” the directionality of the relationship. A review of discussion sections from years and years ago to the present day reveals that it is “always true” that cross-sectional pornography–outcome associations are just as likely due to selective-exposure as sexual socialization; this “never changes,” to quote Anna.

This is, of course, antithetical to science. Nothing is “always true” in science, because scientific knowledge “changes” as new knowledge is generated. According to Arendt and Matthes (2017), “Science is cumulative in the sense that each study builds on previous work” (p. 2). According to Hocking and Miller (1974), “Scientists need not start research from scratch. They can build on the prior body of knowledge” (p. 1). According to Sparks (2013), science is “open to modification–as time passes, new evidence may be expected to revise existing ways of thinking about a phenomenon” (p. 14).

As any reader even casually familiar with the discussion sections of pornography effects papers utilizing cross-sectional data knows, it is a virtual guarantee that the authors will caution that any association they found between pornography use (X) and the belief, attitude, or behavior under study (Y) may be due to “selective-exposure” (i.e., people already in possession of the belief, attitude, or behavioral pattern gravitating to sexual media content that depicts it) not sexual socialization (i.e., people being influenced by the sexual media content in the direction of the belief, attitude, or behavior). In other words, the authors will adopt the stance that despite the pages of conceptual and theoretical arguments they devoted to justifying a X → Y dynamic in their literature review section, it is just as likely the case that Y → X. The author will then call for “longitudinal research” to “untangle” the directionality of the relationship. A review of discussion sections from years and years ago to the present day reveals that it is “always true” that cross-sectional pornography–outcome associations are just as likely due to selective-exposure as sexual socialization; this “never changes,” to quote Anna.

This is, of course, antithetical to science. Nothing is “always true” in science, because scientific knowledge “changes” as new knowledge is generated. According to Arendt and Matthes (2017), “Science is cumulative in the sense that each study builds on previous work” (p. 2). According to Hocking and Miller (1974), “Scientists need not start research from scratch. They can build on the prior body of knowledge” (p. 1). According to Sparks (2013), science is “open to modification–as time passes, new evidence may be expected to revise existing ways of thinking about a phenomenon” (p. 14).

If there were no longitudinal studies comparing the sexual socialization and selective-exposure explanations, it would be quite reasonable for cross-sectional pornography effects studies to invoke the latter as an equally plausible explanation for the significant associations they found between pornography- use and the outcome(s) they studied. Having published a number of cross-lagged longitudinal papers finding evidence for sexual socialization but not selective-exposure, I know that there are such studies, however. A cross-lagged longitudinal study uses panel data to directly compare X → Y and Y → X explanations for the directionality of the XY relation- ship. Because earlier levels of the criterion are included as a covariate, a significant prospective association indicates that the predictor is associated with inter-individual change in the criterion over time.

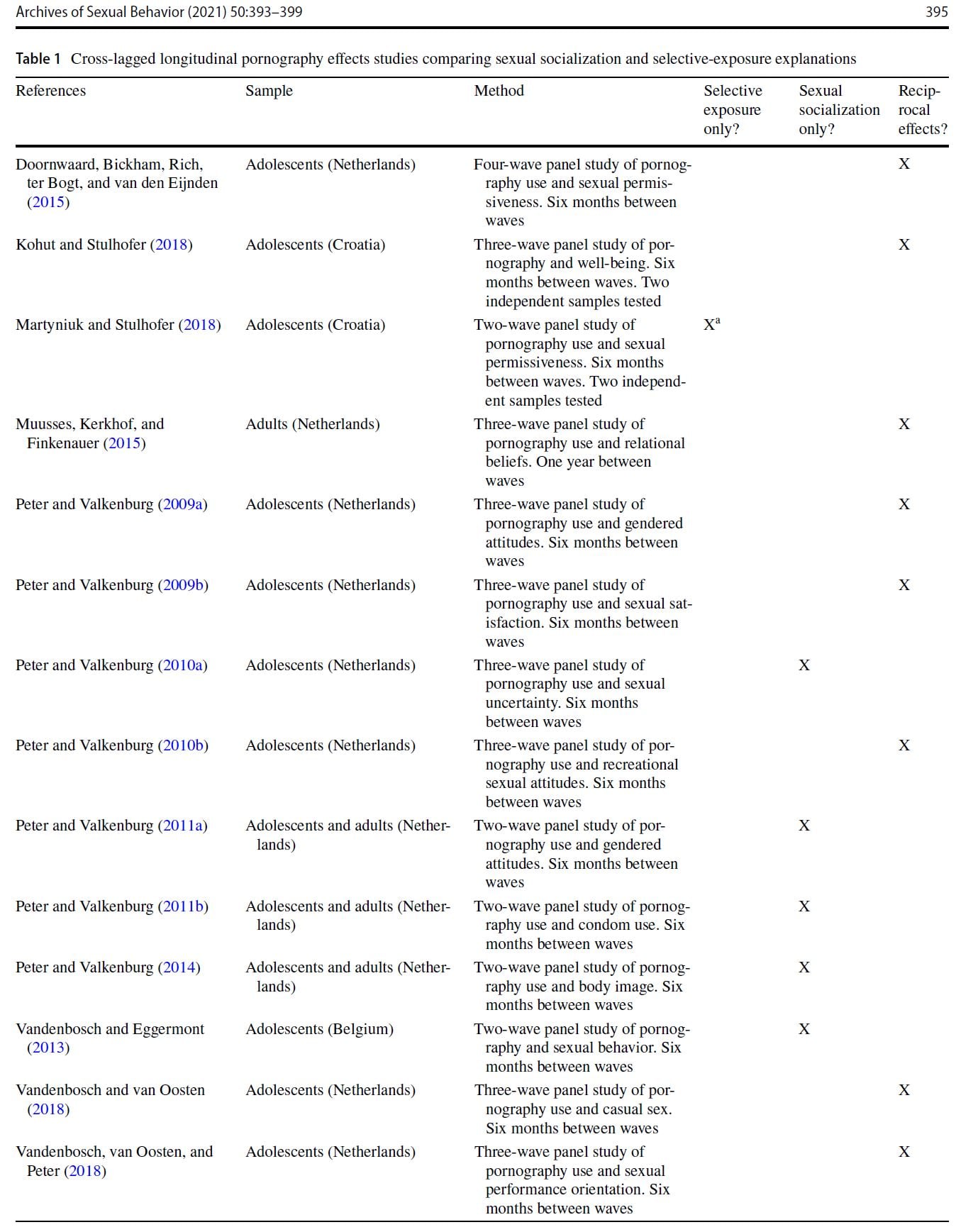

To see if there were other studies beyond my own, I conducted Google Scholar searches using the following sets of terms: (1) “pornography” “selective-exposure” “cross- lagged” and (2) “pornography” “reverse causality” “cross- lagged.” Because both dynamics could be at play (Slater, 2015), I also conducted a search for “pornography” “reciprocal” “cross-lagged.”

The results of these searches are synopsized in Table 1. Of the 25 studies, the majority (14) found evidence of sexual socialization only; earlier pornography use prospectively predicted one or more of the outcomes studied, but the converse was not the case (i.e., prior levels of the outcome or outcomes did not predict later use of pornography). Ten studies found evidence of a reciprocal dynamic (i.e., prior propensities result in some people being more likely to consume pornography than others and these people were impacted subsequently by their exposure). Just one study found evidence of selective-exposure only. However, as detailed in the table footnote, the pattern of correlations overall suggested a pat- tern of either reciprocal influence or no influence in either direction.

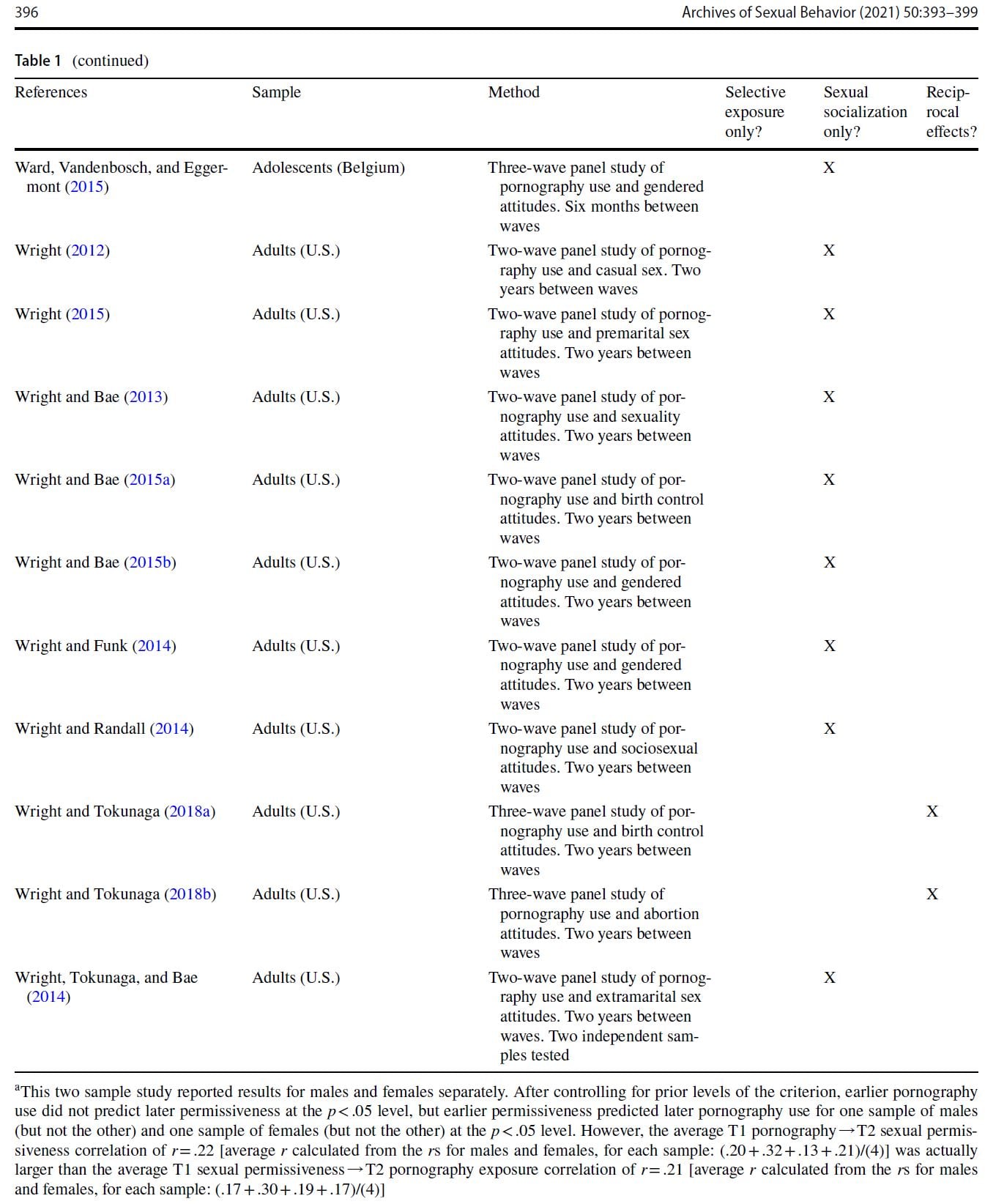

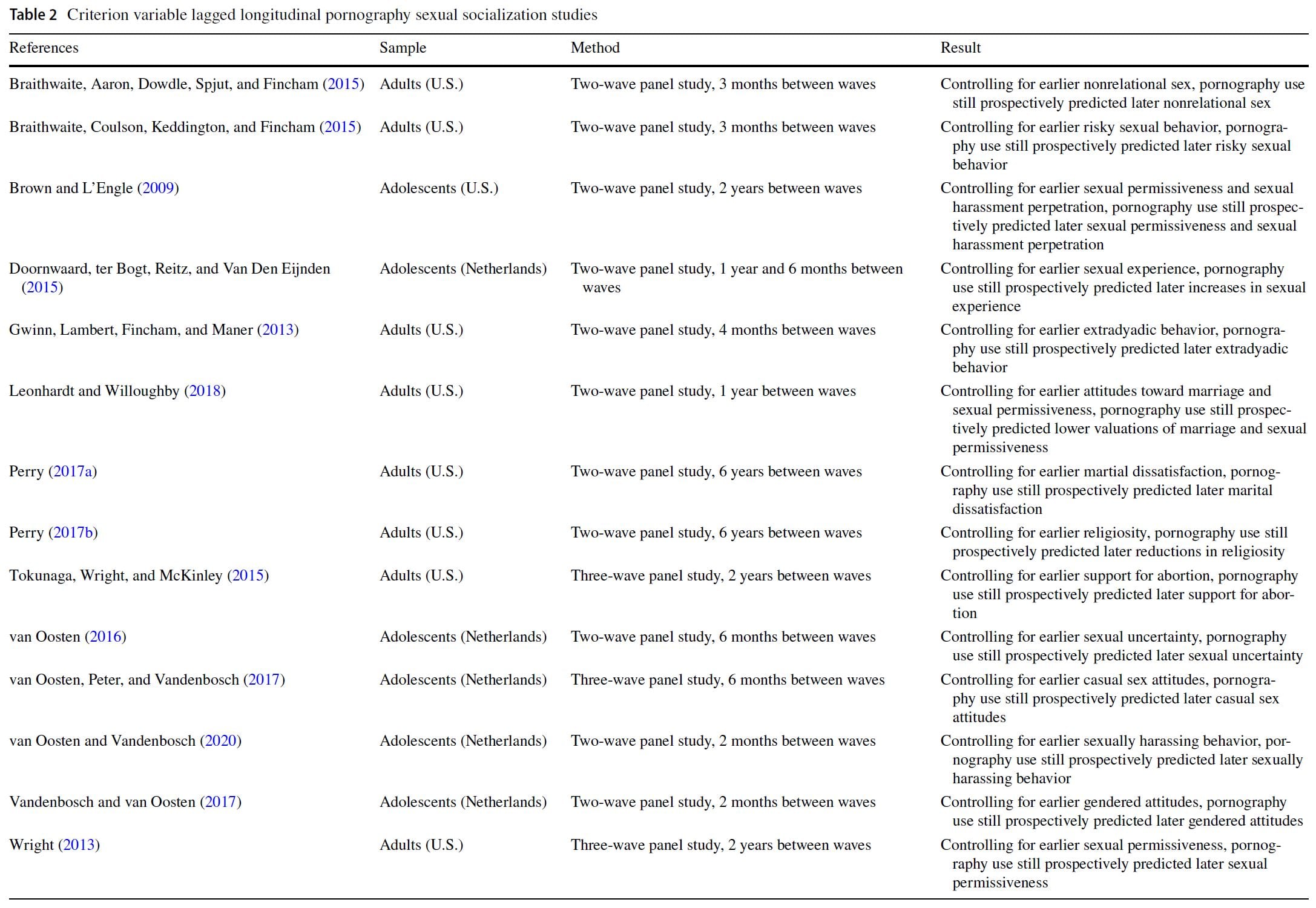

Also of note are longitudinal panel studies that have found significant pornography → outcome associations, after accounting for earlier levels of the outcome. Examples of such studies are listed in Table 2. As Collins et al. (2004) stated in one of the first longitudinal panel studies of media sex effects, “our analyses controlled for adolescents’ level of sexual activity at baseline, rendering an explanation of reverse causality for our findings implausible” (p. 287).

In sum, the notion that significant correlations between pornography use and beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in cross- sectional studies could be due entirely to selective-exposure is in contradiction to the accumulated evidence and could only be supported by a philosophy (to counter quote Arendt & Matthes, 2017; Hocking & Miller, 1974; Sparks, 2013) espousing that science is noncumulative and each study is an isolated fragment that stands entirely on its own; that scientists must start from scratch with each study–they cannot build on the prior body of knowledge; and that science is not open to modification–regardless of the passage of time and new evidence, ways of thinking about a phenomenon should not be revised.

Recommendations to Authors, Editors, and Reviewers

Given the above, I recommend the following to authors, editors, and reviewers of cross-sectional pornography effects research finding theoretically predicted significant associations between pornography use and beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

Authors: Do not state that selective-exposure is an equally plausible alternative explanation for your findings. If reviewers and editors demand you do, provide them with this Letter. If they still demand it, write the obligatory-to-be-published “limitation” statement in a way that absolves you personally from this uninformed opinion and reference this Letter.

Reviewers: Do not ask authors to state that selective exposure is an equally plausible alternative explanation for their results unless you can articulate specifically why their data and findings are such a special and novel case that the accumulated evidence to the contrary is inapplicable. Given the state of the literature, the onus is on you to delineate why the pornographic socialization the authors describe is really just selective-exposure. If the authors make the statement themselves, suggest they remove it and direct them to this Letter.

Editors: Overrule uninformed reviewers who demand that authors make the selective-exposure caveat. Notify authors of this Letter and suggest that while a case for a reciprocal dynamic can be made, a case for selective exposure only is untenable given the state of the literature at present.

Table 1 – Cross-lagged longitudinal pornography effects studies comparing sexual socialization and selective-exposure explanations

Table 2 – Criterion variable lagged longitudinal pornography sexual socialization studies

References

- Arendt, F., & Matthes, J. (2017). Media effects: Methods of hypothesis testing. The InternationalEncyclopedia of Media Effects. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0024.

- Braithwaite, S. R., Aaron, S. C., Dowdle, K. K., Spjut, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). Does pornography consumption increase participation in friends with benefits relationships? Sexuality and Culture, 19, 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9275-4.

- Braithwaite, S. R., Coulson, G., Keddington, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). The influence of pornography on sexual scripts and hooking up among emerging adults in college. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0351-x.

- Brown, J. D., & L’Engle, K. L. (2009). X-rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with US early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research, 36, 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650208326465.

- Collins, R. L., Elliott, M. N., Berry, S. H., Kanouse, D. E., Kunkel, D., Hunter, S. B., & Miu, A. (2004). Watching sex on television predicts adolescent initiation of sexual behavior. Pediatrics, 114, e280–e289. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2003-1065-L.

- Doornwaard, S. M., Bickham, D. S., Rich, M., ter Bogt, T. F., & van den Eijnden, R. J. (2015). Adolescents’ use of sexually explicit internet material and their sexual attitudes and behavior: Parallel development and directional effects. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1476–1488. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000040.

- Doornwaard, S. M., ter Bogt, T. F., Reitz, E., & Van Den Eijnden, R. J. (2015). Sex-related online behaviors, perceived peer norms and adolescents’ experience with sexual behavior: Testing an integrative model. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0127787. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127787.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Gwinn, A. M., Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Maner, J. K. (2013). Pornography, relationship alternatives, and intimate extradyadic behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 699–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613480821.

- Hocking, J. E., & Miller, M. M. (1974, April). Teaching basic communication science concepts. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Communication Association, New Orleans, LA.

- Kohut, T., & Stulhofer, A. (2018). Is pornography use a risk for adolescent well-being? An examination of temporal relationships in two independent panel samples. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202048. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202048.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Leonhardt, N. D., & Willoughby, B. J. (2018). Longitudinal links between pornography use, marital importance, and permissive sexuality during emerging adulthood. Marriage and Family Review, 54, 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1359811.

- Martyniuk, U., & Stulhofer, A. (2018). A longitudinal exploration of the relationship between pornography use and sexual permissiveness in female and male adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.006.

- Muusses, L. D., Kerkhof, P., & Finkenauer, C. (2015). Internet pornography and relationship quality: A longitudinal study of within and between partner effects of adjustment, sexual satisfaction and sexually explicit internet material among newly-weds. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.077.

- Perry, S. L. (2017a). Does viewing pornography reduce marital quality over time? Evidence from longitudinal data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0770-y.

- Perry, S. L. (2017b). Does viewing pornography diminish religiosity over time? Evidence from two-wave panel data. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1146203.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2009a). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit internet material and notions of women as sex objects: Assessing causality and underlying processes. Journal of Communication, 59, 407–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01422.x.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2009b). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit Internet material and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Human Communication Research, 35, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2009.01343.x.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2010a). Adolescents’ use of sexually explicit Internet material and sexual uncertainty: The role of involvement and gender. Communication Monographs, 77, 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2010.498791.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2010b). Processes underlying the effects of adolescents’ use of sexually explicit internet material: The role of perceived realism. Communication Research, 37, 375–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650210362464.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2011a). The influence of sexually explicit internet material and peers on stereotypical beliefs about women’s sexual roles: Similarities and differences between adolescents and adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0189.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2011b). The influence of sexually explicit internet material on sexual risk behavior: A comparison of adolescents and adults. Journal of Health Communication, 16, 750–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.551996.

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2014). Does exposure to sexually explicit Internet material increase body dissatisfaction? A longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.071.

- Slater, M. D. (2015). Reinforcing spirals model: Conceptualizing the relationship between media content exposure and the development and maintenance of attitudes. Media Psychology, 18, 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.897236.

- Sparks, G. G. (2013). Media effects research. Belmont, MA: Wadsworth.

- Tokunaga, R. S., Wright, P. J., & McKinley, C. J. (2015). U.S. adults’ pornography viewing and support for abortion: A three-wave panel study. Health Communication, 30, 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.875867.

- van Oosten, J. M. (2016). Sexually explicit Internet material and adolescents’ sexual uncertainty: The role of disposition-content congruency. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0594-1.

- van Oosten, J. M., Peter, J., & Vandenbosch, L. (2017). Adolescents’ sexual media use and willingness to engage in casual sex: Differential relations and underlying processes. Human Communication Research, 43, 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12098.

- van Oosten, J. M., & Vandenbosch, L. (2020). Predicting the willingness to engage in non-consensual forwarding of sexts: The role of pornography and instrumental notions of sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1121–1132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01580-2.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2013). Sexually explicit websites and sexual initiation: Reciprocal relationships and the moderating role of pubertal status. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12008.

- Vandenbosch, L., & van Oosten, J. M. (2017). The relationship between online pornography and the sexual objectification of women: The attenuating role of porn literacy education. Journal of Communication, 67, 1015–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12341.

- Vandenbosch, L., & van Oosten, J. M. (2018). Explaining the relationship between sexually explicit internet material and casual sex: A two-step mediation model. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1465–1480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1145-8.

- Vandenbosch, L., van Oosten, J. M., & Peter, J. (2018). Sexually explicit internet material and adolescents’ sexual performance orientation: The mediating roles of enjoyment and perceived utility. Media Psychology, 21, 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2017.1361842.

- Ward, L. M., Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). The impact of men’s magazines on adolescent boys’ objectification and courtship beliefs. Journal of Adolescence, 39, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.12.004.

- Wright, P. J. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of U.S. adults’ pornography exposure: Sexual socialization, selective-exposure, and the moderating role of unhappiness. Journal of Media Psychology, 24, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000063.

- Wright, P. J. (2013). A three-wave longitudinal analysis of preexisting beliefs, exposure to pornography, and attitude change. Communication Reports, 26, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2013.773053.

- Wright, P. J. (2015). Americans’ attitudes toward premarital sex and pornography consumption: A national panel analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0353-8.

- Wright, P. J. (2021). Overcontrol in pornography research: Let it go, let it go… [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01902-9.

- Wright, P. J., & Bae, S. (2013). Pornography consumption and attitudes toward homosexuality: A national longitudinal study. Human Communication Research, 39, 492–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12009.

- Wright, P. J., & Bae, S. (2015a). US adults’ pornography consumption and attitudes toward adolescents’ access to birth control: A national panel study. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.944294.

- Wright, P. J., & Bae, S. (2015b). A national prospective study of pornography consumption and gendered attitudes toward women. Sexuality & Culture, 1, 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-014-9264-z.

- Wright, P. J., & Funk, M. (2014). Pornography consumption and opposition to affirmative action for women: A prospective study. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 208–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313498853.

- Wright, P. J., & Randall, A. K. (2014). Pornography consumption, education, and support for same-sex marriage among adult US males. Communication Research, 41, 665–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212471558.

- Wright, P. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2018a). Linking pornography consumption to support for adolescents’ access to birth control: Cumulative results from multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal national surveys. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2018.1451422.

- Wright, P. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2018b). Pornography consumption, sexual liberalism, and support for abortion in the United States: Aggregate results from two national panel studies. Media Psychology, 21, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1267646.

- Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Bae, S. (2014). More than a dalliance? Pornography consumption and extramarital sex attitudes among married U.S. adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3, 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000024.