COMMENTS: In this study, participants were asked about their sexual arousal related to 27 genres (themes) of porn. Why the researchers chose these 27 particular genres is known only to them. How the authors determined which genres were “mainstream” which were “non-mainstream” also remains a mystery given their seemingly random categorization (more below).

No matter, this study debunks the claim that porn users like only a narrow range of genres. While it doesn’t directly ask about escalation over time, the study found that subjects the authors categorized as “non-mainstream” porn viewers like many different types of porn (see the researchers’ arbitrary categorization of porn genres below). A few excerpts:

The findings suggest that in classified non-mainstream Sexually Explicit Media [porn] groups, patterns of sexual arousal might be less fixated and category specific than previously assumed.

Particularly for heterosexual men and non-heterosexual women, who were characterized by substantial levels of sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM themes, the findings suggest that patterns of sexual arousal induced by SEM in non-laboratory settings might be more versatile, less fixed, and less category specific than previously assumed. This supports a more generalized SEM arousability and indicates that non-mainstream SEM group participants also are aroused by more mainstream (“vanilla”) themes.

The study is saying that so-called “non-mainstream porn viewers” are aroused by all sorts of porn, whether it’s so-called “mainstream” (Bukkake, Orgy, Fist-fucking) or so-called “non-mainstream” (Sadomasochism, Latex). This finding debunks the often repeated meme that frequent porn users stick to one type of porn. (An example of the unfounded claim about “fixed” tastes is Ogas and Gaddam’s highly criticized book A Billion Wicked Thoughts.)

However, the authors’ biases shine through when they try to spin this finding as evidence against porn users escalating into new genres. In this excerpt the authors falsely assert that if escalation existed porn users who escalated would no longer (ever) find previous genres arousing (huh?):

In the context of SEM research, the findings of more generalized patterns of sexual arousal among non-mainstream SEM user groups can be interpreted as diverging from the progressive satiation hypothesis, which assumes that progressively more “extreme” (non-mainstream) SEM contents are needed to elicit sexual arousal.32 At least at a group level, our results do not seem to corroborate this hypothesis, because sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM content did not exclude arousal to less “extreme” (mainstream) SEM content in classified non-mainstream SEM groups.

The authors are claiming that being aroused by non-mainstream genre (i.e. Violent sex) should preclude a porn viewer from being aroused by a genre of so-called mainstream porn (i.e. Gangbang). This is nonsense and unsupported by other studies. In fact the study they cite as support (citation 32) actually found the opposite: 99.5% of participants who had escalated to deviant pornography (bestiality or child porn) were also still using and collecting non-deviant porn. See – Does deviant pornography use follow a Guttman-like progression?

I guess we shouldn’t be surprised by this level of misrepresentation as the lead author is Gert Hald, the mastermind behind the egregious pornography use questionnaire, the Pornography Consumption Effect Scale (PCES). See a critique of the PCES here: Self-Perceived Effects of Pornography Consumption (Hald & Malamuth 2008).

Now, let’s turn to the authors’ arbitrary categorization of porn genres as either “mainstream” or “non-mainstream.”

As the purpose of this study was to compare “mainstream” porn users to “non-mainstream” porn users, categorization determines all these authors’ findings. And, how is it determined which porn genre is mainstream and which is non-mainstream? It appears quite arbitrary as Orgy and Bukkake are mainstream, yet “latex” is considered non-mainstream porn.

How are “Enemas” labeled mainstream while “Bondage” is categorized as non-mainstream? How can this be with Fifty Shades of Grey selling over 125 million copies, followed by sequels and three profitable screen adaptations? Fifty Types of Enemas hasn’t made it to a theater near you, and probably never will.

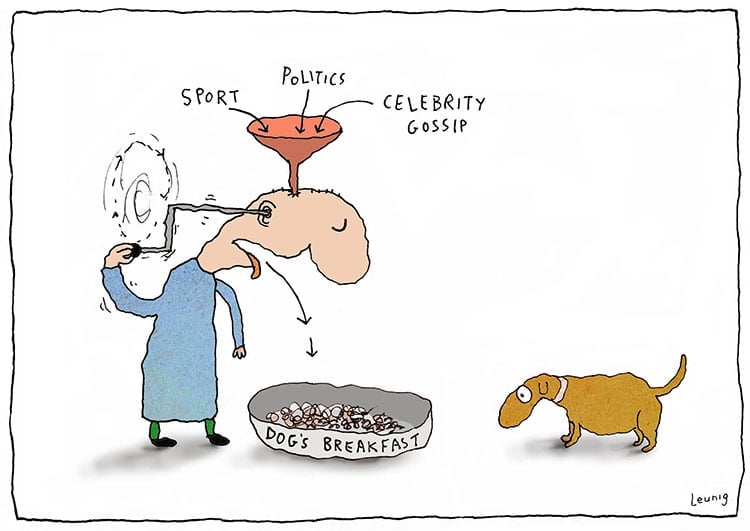

Why are there 5 non-mainstream genres, yet 22 mainstream genres? And why is “Other” listed as mainstream when it could be anything, including bestiality or child porn? What a dog’s breakfast!

Here are the study’s categories:

Mainstream porn:

- Amateur

- Anal sex

- Big breasts

- Huge penises

- Bisexual

- Bukkake

- Cumshot

- Fat girls (“big beautiful women [BBW]”)

- Fist fucking

- Gangbang (1 woman + ≥3 men)

- Gay

- Lesbian

- Threesomes

- Orgy (more women and men)

- Lolita (teen)

- Mature (“mother/mom/mama I’d like to fuck [MILF]”)

- Masturbation (including sex toys)

- Oral sex

- Softcore (non-explicit)

- Golden showers (including enemas)

- Vaginal sex

- Other

Non-mainstream porn:

- Sadomasochism

- Violent sex (simulated rape, aggression and coercion)

- Bizarre or extreme

- Bondage and dominance (including disciplining)

- Fetish (including latex)

UPDATE 2019: Author Alexander Štulhofer confirmed his extreme agenda-driven bias when he joined allies Nicole Prause, David Ley and others in trying to silence YourBrainOnPorn.com. Štulhofer and other pro-porn “experts” at www.realyourbrainonporn.com are engaged in illegal trademark infringement and squatting. Štulhofer was a sent cease and desist letter. Legal actions continue to be pursued.

Gert Martin Hald, PhD ,Aleksandar Stulhofer, PhD, Theis Lange, PhD

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.11.001

Abstract

Introduction

Investigations of patterns of sexual arousal to certain groups of sexually explicit media (SEM) in the general population in non-laboratory settings are rare. Such knowledge could be important to understand more about the relative specificity of sexual arousal in different SEM users.

Aims

(i) To investigate whether sexual arousal to non-mainstream vs mainstream SEM contents could be categorized across gender and sexual orientation, (ii) to compare levels of SEM-induced sexual arousal, sexual satisfaction, and self-evaluated sexual interests and fantasies between non-mainstream and mainstream SEM groups, and (iii) to explore the validity and predictive accuracy of the Non-Mainstream Pornography Arousal Scale (NPAS).

Methods

Online cross-sectional survey of 2,035 regular SEM users in Croatia.

Main Outcomes Measures

Patterns of sexual arousal to 27 different SEM themes, sexual satisfaction, and self-evaluations of sexual interests and sexual fantasies.

Results

Groups characterized by sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM could be identified across gender and sexual orientation. These non-mainstream SEM groups reported more SEM use and higher average levels of sexual arousal across the 27 SEM themes assessed compared with mainstream SEM groups. Only few differences were found between non-mainstream and mainstream SEM groups in self-evaluative judgements of sexual interests, sexual fantasies, and sexual satisfaction. The internal validity and predictive accuracy of the NPAS was good across most user groups investigated.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that in classified non-mainstream SEM groups, patterns of sexual arousal might be less fixated and category specific than previously assumed. Further, these groups are not more judgmental of their SEM-related sexual arousal patterns than groups characterized by patterns of sexual arousal to more mainstream SEM content. Moreover, accurate identification of non-mainstream SEM group membership is generally possible across gender and sexual orientation using the NPAS.

Hald GM, Stulhofer A, Lange T, et al. Sexual Arousal and Sexually Explicit Media (SEM): Comparing Patterns of Sexual Arousal to SEM and Sexual Self-Evaluations and Satisfaction Across Gender and Sexual Orientation. Sex Med 2017;X:XXX–XXX.

Key Words:

Sexually Explicit Media, Pornography, Sexual Arousal, Self-Evaluations

Introduction

Sexual arousal to sexually explicit media (SEM) has traditionally been studied in the laboratory by exposing participants to different kinds of SEM. The conclusions emerging from these studies generally suggest that patterns of sexual arousal are more sensitive to context and less sensitive to the actor for women than for men.1, 2, 3 However, very little research has investigated sexual arousal in relation to the actual SEM contents and themes (eg, oral, anal, gangbang, etc) people have been exposed to or report using.1, 4, 5, 6, 7

Among sex offenders, particularly those convicted of sexually violent or underage sexual offenses, sexual arousal to SEM contents congruent with the convicted crimes has been studied.8, 9 This research generally suggests significantly higher levels of sexual arousal to SEM among sexual offenders than among controls (eg, non-offenders or offenders not convicted of sexual crimes) when the SEM content is congruent with the nature of the offense.9, 10, 11, 12

Contrary to research involving convicted sexual offenders or laboratory studies, non-laboratory investigations of SEM-related sexual arousal patterns in the general population are rare.6 Further, research investigating whether non-mainstream arousal groups might be identified based on patterns of sexual arousal to SEM contents is missing from the literature on SEM.6, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Such identification could be useful because it does not rely on the individual’s ability to identify or recognize what might be considered “non-mainstream” SEM. Further, such identification is based solely on actual patterns of sexual arousal to specific SEM contents as opposed to viewing habits, which might be (more) subject to the availability of the desired SEM contents.6, 7 In accord with the Non-Mainstream Pornography Arousal Scale (NPAS), non-mainstream SEM refers to patterns of sexual arousal to the SEM categories of (i) sadomasochism, (ii) fetishism, (iii) violent sex (including simulated rape, aggression, and coercion), (iv) bondage and dominance (including discipline), and (v) bizarre or extreme SEM6, 7 as identified by latent class analyses. Accordingly, the 1st aim of this study was to investigate whether non-mainstream SEM groups could be identified across gender and sexual orientation based on self-reported sexual arousal to 27 different SEM contents.

Little is known about systematic differences in individuals reporting sexual arousal to non-mainstream vs mainstream SEM in their sexual satisfaction and self-evaluative judgments of their sexual interests and fantasies. Research involving individuals with non-mainstream sexual arousal patterns (eg, a paraphilia) has suggested that increased self- and societal stigmatization, negative judgments, and evaluations of mental health could be present.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Such factors might adversely influence sexual satisfaction and individual judgments about sexual interests and fantasies among SEM minority user groups such as non-mainstream SEM users.19, 20 Therefore, the 2nd aim of this study was to investigate how patterns of SEM-induced sexual arousal, sexual satisfaction, and self-evaluated sexual interests and fantasies compare in groups characterized by sexual arousal to non-mainstream vs mainstream SEM.

Recently, Hald and Štulhofer6, 7 developed the NPAS. The NPAS is a 5-item scale measuring non-mainstream SEM-related patterns of sexual arousal (see also the Main Outcome Measures). However, further validation of the NPAS in relation to its actual ability to correctly predict non-mainstream SEM arousal group membership has not been conducted but has been called for.7 Accordingly, a 3rd aim of this study was to investigate the ability of the NPAS to correctly predict non-mainstream SEM group membership.

This study used the same dataset that was recently used to develop the NPAS.6, 7 In connection to the 3rd study aim, the present findings should be considered an internal validation of the original measure to thoroughly test the robustness and precision of the NPAS.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data from a larger dataset collected in an online study focusing on SEM use, sexual health, and relationship quality in Croatia were used. Because individuals who rarely used SEM were of little, if any, relevance for the planned analyses, only participants who reported using SEM at least “several times” in the previous 12 months were included in this study. In this regard, women had higher odds than men (odds ratio = 0.16, P < .05) of belonging to the group of participants who rarely used SEM. There were no significant age or educational differences between participants who used SEM rarely and the rest of the sample.

2,035 participants with no missing values on questions regarding sexual arousal to different SEM content were included in the analyses. Most included participants (58.2%, n = 1,185) were women. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 60 years (mean age = 30.75, SD = 9.47). Most participants (57.8%) had a college or university education; 41.0% had a secondary education. In contrast to the 15.7% of participants who reported that their monthly household income was lower than the national average, more than 1 fourth (27.8%) reported a higher-than-average household income. Most of the sample reported being in a relationship (47.6%) or married (24.0%), with less 1 third (28.4%) reporting being single. Apart from “weddings, funerals, and family holidays,” a substantial proportion of participants (45%) never attended religious ceremonies.

The survey, conducted over 10 days in April 2014, was hosted on a commercial site dedicated to online research. Participant recruitment was diverse, including banners posted on Facebook, 2 major news websites, an online dating website, and a popular women’s magazine website. Participants’ IP addresses were not permanently recorded to ensure anonymity. Basic information about the study and other details needed for informed consent were provided at the 1st survey screen. Before accessing the questionnaire, participants had to confirm that they were of legal age (ie, ≥18 years). Study procedures were approved by the ethical review board of the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb.

Main Outcome Measures

Below we present the indicators relevant for this study. The average time to complete the survey was just under 22 minutes.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation was investigated using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = exclusively homosexual to 5 = exclusively heterosexual). In accord with Hald and Štulhofer,6 participants’ responses were dichotomized into the following categories: 0 = exclusively heterosexual (5) and 1 = non-heterosexual (1–4) to ensure adequate statistical power in the analyses.

Sexual Satisfaction and Self-Evaluations

The 12-item version of the New Scale of Sexual Satisfaction21 was used to assess sexual satisfaction in the previous 6 months. This composite measure showed excellent internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach α = 0.93), with higher scores indicating higher sexual satisfaction. To address participants’ self-evaluation of their sexual interest and fantasies, the following 2 items were used: “My sexual interest is completely healthy” and “My sexual fantasies make me a bad person.” Responses were given using a 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from 1 = does not apply to me at all to 5 = applies to me completely. The 2 items were only weakly correlated (r = −0.21).

SEM Use and Specific SEM Contents

The frequency of SEM use in the previous 12 months was measured using an 8-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 8 = daily or almost daily. Participants were asked about their sexual arousal related to 27 specific SEM themes using the following generic question: “Please indicate how arousing you find each of the following types of SEM?” (Table 1). Responses were provided using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large extent). The themes were chosen according to Hald22 and publicly available lists of the most frequently used search terms and types of SEM were accessed as provided by large commercial SEM sites.23, 24

Table 1 Overview of sexually explicit media content themes | |

Description | Reference number |

| Amateur | 1 |

| Anal sex | 2 |

| Big breasts | 3 |

| Huge penises | 4 |

| Bisexual | 5 |

| Bizarre or extreme | 6∗ |

| Bondage and dominance (including disciplining) | 7∗ |

| Bukkake | 8 |

| Cumshot | 9 |

| Fat girls (“big beautiful women [BBW]”) | 10 |

| Fist fucking | 11 |

| Gangbang (1 woman + ≥3 men) | 12 |

| Gay | 13 |

| Lesbian | 14 |

| Threesomes | 15 |

| Orgy (more women and men) | 16 |

| Lolita (teen) | 17 |

| Mature (“mother/mom/mama I’d like to fuck [MILF]”) | 18 |

| Masturbation (including sex toys) | 19 |

| Oral sex | 20 |

| Sadomasochism | 21∗ |

| Violent sex (simulated rape, aggression and coercion) | 22∗ |

| Softcore (non-explicit) | 23 |

| Golden showers (including enemas) | 24 |

| Vaginal sex | 25 |

| Fetish (including latex) | 26∗ |

| Other | 27 |

∗This theme is categorized as “non-mainstream” according to the Non-Mainstream Pornography Arousal Scale.6, 7

Sexual Arousal to Non-Mainstream SEM Content

The 5-item NPAS composite measure was used as an indicator of sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM content (see also 6, 7). The NPAS was developed to measure non-mainstream SEM-related patterns of sexual arousal based on self-reported sexual arousal to 27 different SEM themes. Across gender and sexual orientation, the strongest indicators of the latent non-mainstream SEM factor included the following 5 non-mainstream SEM themes: (i) sadomasochism, (ii) fetishism (including latex), (iii) violent sex (including simulated rape, aggression, and coercion), (iv) bondage and dominance (including discipline), and (v) bizarre or extreme SEM.6, 7 No specific definition of each theme is provided by the NPAS. Participants were asked to indicate how arousing they found each of the 5 themes using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = to a very large extent).

Statistical Analysis

The overall analytic strategy had 5 steps. Latent class analysis was used to identify clusters based on reported levels of sexual arousal to 27 different SEM themes. This procedure provided purely data-driven grouping. The number of classes was determined using the Bayesian information criterion. The model was fitted with Mclust 5.0.1 in R 3.1.2.25, 26 Using mean sexual arousal to SEM theme values, the 10 most sexually arousing themes and the 10 least arousing themes were identified for each latent class. Next, we inspected the occurrence of the NPAS 5 non-mainstream themes among the 10 most arousing and 10 least arousing SEM themes. A single (non-mainstream arousal) score for each class was computed by subtracting the number of non-mainstream themes found in the 10 least arousing themes from the number of non-mainstream themes among the 10 most arousing SEM themes. Latent classes with a score of at least 3 were categorized as non-mainstream sexual arousal groups (Table 2), and all others were categorized as mainstream sexual arousal groups.

Table 2Number of non-mainstream SEM themes for the identified latent classes stratified by gender and sexual orientation∗ | ||||||||||||||||

Heterosexual men (n = 586) | Non-heterosexual men (n = 264) | Heterosexual women (n = 722) | Non-heterosexual women (n = 463) | |||||||||||||

SEM sexual arousal groups | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G1 | G2 | G3 | G42 | G13 | G23 | G3 | G4 | G1 | G24 | G3 | G4 |

| Count (%) | 220 (37) | 200 (34) | 127 (22) | 39 (7) | 113 (43) | 79 (30) | 47 (18) | 25 (9) | 57 (8) | 295 (41) | 90 (12) | 280 (39) | 113 (24) | 129 (28) | 14 (3) | 207 (45) |

| (A) Number of non-mainstream themes among the 10 most important themes for classification | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| (B) Number of non-mainstream themes among the 10 least important themes for classification | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Total score (A + B) | −5 | −1 | 5 | 2 | −3 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | −5 | 0 | −4 | 5 | 1 | −4 |

G = group; SEM = sexually explicit media.

∗Groups (latent classes) characterized by non-mainstream sexual arousal patterns are presented in boldface type, whereas groups characterized by mainstream sexual arousal patterns are not. The total score (A + B) represents the number of non-mainstream themes (total = 5; Table 1) among the 10 most important themes for the particular group subtracted by the number of non-mainstream themes among the 10 least important themes for the particular group. Latent classes with a score of at least 3 were categorized as “sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM content groups,” whereas all other classes were treated as “sexual arousal to mainstream SEM content groups.”

Once the obtained latent classes had been identified as non-mainstream or mainstream, they were compared for age and frequency of SEM use in the previous 12 months using t-tests. Next, multiple logistic regression analysis with membership in non-mainstream vs mainstream groups as the outcome was used to explore its association with NPAS scores. Analyses were adjusted for age and frequency of SEM use. Receiver-operating characteristics curves were used to further quantify the predictive ability of the NPAS. Informed by seminal work on sexual arousal,1, 27 all analyses were stratified by gender and sexual orientation.

Results

For to the 1st study aim, latent class analysis was used to assess the degree to which participants’ self-reported sexual arousal to 27 different SEM themes could be categorized into distinct latent classes. The mean vector for each group (ie, latent class) is presented graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Average levels of sexual arousal across the 27 sexually explicit media themes investigated. Circles, triangles, crosses, and stars denote latent classes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, as classified in Table 2. Overview of sexually explicit media themes by number is presented in Table 1. Scores for each theme have been adjusted to have 0 mean across gender and sexual orientation strata; y-axes differ in scale among plots. For exclusively heterosexual men, the non-mainstream sexually explicit media sexual arousal group is represented by crosses. For non-exclusively heterosexual men, the non-mainstream sexually explicit media sexual arousal group is represented by stars. For exclusively heterosexual women, the non-mainstream sexually explicit media sexual arousal groups are represented by triangles and circles. For non-exclusively heterosexual women, the sexually explicit media non-mainstream sexual arousal group is represented by triangles. All other groups are composed of participants characterized by sexual arousal to mainstream sexually explicit media contents.

View Large Image | View Hi-Res Image | Download PowerPoint Slide

The Bayesian information criterion indicated that 4 latent classes were the most appropriate solution across all 4 strata (women vs men and exclusively heterosexual vs non-heterosexual). Next, we inspected the 10 most arousing and the 10 least arousing SEM themes by group and calculated the total non-mainstream arousal score for each group (Table 1).

The composition of each group is presented in Table 2. In each stratum, except for exclusively heterosexual women, 1 latent class was clearly characterized by high arousal to non-mainstream SEM themes. For exclusively heterosexual women, 2 such latent class groups were observed. The non-mainstream group was very small only for non-heterosexual men (n = 25, 9.5%). For heterosexual men and non-heterosexual women, more than 1 fifth of participants were classified in the non-mainstream arousal group (n = 127, 21.7%; n = 129, 27.9%, respectively), which was still markedly lower than for heterosexual women of whom almost half were classified in 1 of the 2 non-mainstream arousal groups (n = 332, 46.0%). These findings confirm that non-mainstream SEM user group can be identified based on self-reported sexual arousal to 27 different SEM contents across gender and sexual orientation.

Non-mainstream SEM group participants were compared with mainstream SEM group participants for differences in age and frequency of SEM use in the previous 12 months (Table 3). Age differences were significant only for heterosexual men (t584 = 2.07, P < .05, Cohen d = 0.17) and non-heterosexual women (t461 = 3.01, P < .01, Cohen d = 0.28). In 3 of the 4 subsamples, the frequency of SEM use was significantly higher among non-mainstream SEM group participants compared with mainstream SEM group participants (heterosexual men, t584 = −2.97, P < .001, Cohen d = 0.031; heterosexual women, t631 = −7.17, P < .001, Cohen d = 0.55; non-heterosexual women, t233 = −6.27, P < .0001, Cohen d = 0.64).

Table 3Differences among latent class groups in age, SEM use, self-evaluated sexual interest, sexual fantasies, and sexual satisfaction∗ | |||||||||||||

Heterosexual men | Non-heterosexual men | Heterosexual women | Non-heterosexual women | ||||||||||

SEM sexual arousal groups | SEM sexual arousal groups | SEM sexual arousal groups | SEM sexual arousal groups | ||||||||||

G1, 2, 4 (n = 459) | G3 (n = 127) | G1–3 (n = 239) | G4 (n = 25) | G3–4 (n = 390) | G1–2 (n = 332) | G1, 3, 4 (n = 334) | G2 (n = 129) | ||||||

Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t†† (df) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t†† (df) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t†† (df) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t†† (df) | ||

| Age | 36.32 (9.80) | 34.32 (9.00) | 2.07‡ (584) | 33.14 (10.08) | 35.40 (9.32) | −1.08 (262) | 28.18 (8.48) | 27.85 (7.72) | 0.55 (720) | 27.62 (7.33) | 25.36 (6.97) | 3.01‡ (461) | |

| Frequency of pornography use in past 12 mo | 6.14 (1.01) | 6.43 (0.87) | 2.97‡ (584) | 6.44 (0.84) | 6.64 (0.70) | −1.15 (262) | 4.79 (0.97) | 5.39 (1.21) | 7.17‡‖ (631) | 5.25 (1.09) | 5.95 (1.09) | 6.27‡‖ (233) | |

| My sexual interest is healthy | 4.48 (0.76) | 4.27 (0.91) | 2.42‡ (177) | 4.16 (0.85) | 4.16 (0.62) | .02 (261) | 4.55 (0.70) | 4.45 (0.86) | 1.70 (636) | 4.38 (0.79) | 4.20 (0.96) | 1.91 (197) | |

| My sexual fantasies make me a bad person | 1.38 (0.80) | 1.63 (1.12) | −2.40‡ (163) | 1.55 (1.00) | 2.08 (1.32) | −1.96 (27) | 1.36 (0.87) | 1.45 (0.99) | 1.27 (664) | 1.45 (0.98) | 1.40 (0.82) | 0.52 (458) | |

| Sexual satisfaction | 46.81 (9.30) | 45.60 (8.43) | 1.25 (512) | 45.89 (9.42) | 44.27 (7.34) | 0.78 (221) | 48.05 (8.80) | 47.38 (9.43) | 0.95 (664) | 45.77 (9.16) | 46.22 (10.01) | −0.43 (404) | |

G = group; SEM = sexually explicit media.

∗Groups (latent classes) characterized by non-mainstream sexual arousal patterns are presented in boldface type, whereas groups characterized by mainstream sexual arousal patterns are not.

†Between-group differences.

‡P < .05; §P < .01; ‖P < .001.

For the 2nd study aim, participants from non-mainstream SEM groups generally reported higher average levels of sexual arousal to the 27 SEM themes assessed than participants from mainstream SEM groups. This was the case across gender and sexual orientation. Figure 1 shows that the level of sexual arousal curves in mainstream arousal groups essentially follow the same pattern and ordering of responses across the 27 SEM themes. This pattern appears particularly pronounced for men and non-heterosexual women and less clear for heterosexual women.

As presented in Table 3, evaluations of one’s sexual interests and fantasies were significantly different between mainstream and non-mainstream arousal groups only in exclusively heterosexual men. Heterosexual men from the mainstream arousal group judged their sexual interests as significantly more healthy and less negative compared with men from the non-mainstream group, with the magnitude of these differences being small (t177 = 2.42, P < 0.05, Cohen d = 0.25; t163 = −2.40, P < .05, Cohen d = 0.26, respectively). No differences in sexual satisfaction between mainstream and non-mainstream arousal groups were found across gender and sexual orientation.

For the 3rd study aim (ability of NPAS to correctly predict membership in the non-mainstream SEM arousal group), multiple logistic regression analyses were carried out by gender and sexual orientation. Controlling for age and frequency of SEM use, higher NPAS scores significantly increased the odds of membership in the non-mainstream SEM group in all 4 strata (adjusted odds ratio = 1.66–2.39, P < .001). NPAS scores consistently predicted membership in the non-mainstream SEM group substantially better than what would be expected by chance. The predictive efficacy of the scale was lowest for non-heterosexual men and heterosexual women, for whom 68% and 71%, respectively, of target cases were correctly classified. For heterosexual men and non-heterosexual women, the predictive efficacy was 79% and 96%, respectively.

Receiver-operating characteristics analysis28 was applied to provide information about the efficiency of the NPAS in distinguishing non-mainstream SEM group participants from mainstream SEM group participants. The analyses suggested that the measure had high precision among heterosexual men (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.91–0.97) and non-heterosexual men (AUC = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.95–0.99) and among non-heterosexual women (AUC = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.93–0.97). Among heterosexual women, the precision of the NPAS was found to be mediocre (AUC = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.83–0.89), which is in line with our earlier observations (Table 4).

Table 4Predicting membership of the sexual arousal to non-mainstream sexually explicit media group using the NPAS | ||||

Heterosexual men (n = 586) | Non-heterosexual men (n = 264) | Heterosexual women (n = 722) | Non-heterosexual women (n = 256) | |

| NPAS score, AOR∗ (95% CI) | 2.21 (1.91–2.56)‡‡ | 2.39 (1.68–3.42)‡‡ | 1.66 (1.53–1.79)‡‡ | 3.22 (2.09–4.96)‡‡ |

| Total predicted membership, % | 93.7 | 95.1 | 78.5 | 96.1 |

| Target group†† predicted membership, % | 78.7 | 68.0 | 71.1 | 96.1 |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; NPAS = Non-Mainstream Pornography Arousal Scale.

∗Adjusted for age and frequency of sexually explicit media use in the past 12 months.

†Sexually aroused to non-mainstream sexually explicit media group.

‡P < .001.

Discussion

This study found that SEM user groups characterized by patterns of sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM could be identified across gender and sexual orientation based on their self-reported sexual arousal to 27 different SEM contents using latent class analyses. Further, the study found very few differences between these groups and mainstream SEM groups in sexual satisfaction and self-evaluation of sexual interests and fantasies. The study also found that non-mainstream SEM group participants generally reported higher average levels of sexual arousal across the 27 SEM themes investigated compared with mainstream SEM group participants. This pattern of response was especially pronounced for men and non-heterosexual women. In addition, the study found that the internal validity and predictive accuracy of the NPAS were good to excellent for all groups, except heterosexual women, for whom it was mediocre.

Particularly for heterosexual men and non-heterosexual women, who were characterized by substantial levels of sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM themes, the findings suggest that patterns of sexual arousal induced by SEM in non-laboratory settings might be more versatile, less fixed, and less category specific than previously assumed.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 This supports a more generalized SEM arousability and indicates that non-mainstream SEM group participants also are aroused by more mainstream (“vanilla”) themes. These findings differ somewhat from clinical practice involving patients presenting with non-mainstream sexual arousal problems (eg, paraphilias), in whom patterns of sexual arousal often are reported to be more fixed and narrowly defined.29, 30, 31 We speculate that the main reason for this discrepancy is that in clinical settings individuals presenting with a non-mainstream sexual arousal problem are likely to constitute a subgroup of individuals for whom these sexual arousal patterns are more exclusively, strongly, and narrowly related to their non-mainstream sexual preferences than the groups described in the present study.31 Another explanation could be related to the way our survey was advertised. If we recruited individuals who were, on average, more experienced in SEM use than their peers, then the less fixed pattern of arousal to SEM might be the consequence of this more extensive SEM use, which also could include more mainstream SEM usage.

In the context of SEM research, the findings of more generalized patterns of sexual arousal among non-mainstream SEM user groups can be interpreted as diverging from the progressive satiation hypothesis, which assumes that progressively more “extreme” (non-mainstream) SEM contents are needed to elicit sexual arousal.32 At least at a group level, our results do not seem to corroborate this hypothesis, because sexual arousal to non-mainstream SEM content did not exclude arousal to less “extreme” (mainstream) SEM content in classified non-mainstream SEM groups.

The study did not find differences between non-mainstream and mainstream SEM groups with regard to their sexual satisfaction and judgements of their sexual interests and fantasies with the exception of exclusively heterosexual men. Across gender and sexual orientation, participants generally judged their sexual interests as “healthy” and that their sexual fantasies did not make them a “bad” person. These findings indicate that individuals sexually aroused by non-mainstream SEM contents do not self-stigmatize in a way that adversely affects their sexual satisfaction or judgements about their sexual interests and fantasies.

Among heterosexual men, mainstream SEM groups evaluated their sexual interests as significantly more healthy and their sexual fantasies as less “bad” than their non-mainstream peers. However, because the magnitude of these differences was modest, the constructs were assessed using single-item indicators, and because we lack a body of research with which to adequately contextualize these findings, we refrain from elaborating further on this particular finding. Instead, we call for future research to more thoroughly explore these preliminary findings in a way that increases their reliability and validity.

In the investigation of the predictive accuracy of Hald and Štulhofer’s NPAS,6 controlling for age and frequency of SEM consumption, the findings showed good internal validity and the scale consistently predicted target group membership across gender and sexual orientation significantly better than what would be expected by chance. The predictive efficacy of the scale was lowest for non-heterosexual men and heterosexual women. However, the application of receiver-operating characteristics curves suggested that the precision of the scale was good to excellent28 for all groups except heterosexual women.

A reason for a relative lower predictive efficacy of the NPAS in the case of non-heterosexual men could be the fact that the initial classification of non-mainstream sexual arousal included gay sex-related themes, which non-heterosexual men would likely find more arousing than (exclusively) heterosexual men.33 This would weaken the discriminative ability of the NPAS in this group. For heterosexual women, in whom the NPAS systematically underperformed, there could different reasons for this. (i) There seems to be a tendency in the contemporary popular culture to mainstream 2 of the themes that featured prominently in the classification of the non-mainstream SEM groups, namely (i) sadomasochism and (ii) bondage, dominance, and discipline. The popularization of these categories by books and movies such as Fifty Shades of Grey seems to primarily affect heterosexual women.19, 20, 34 (ii) Our sample contained a larger proportion of well-educated women. Because education has been closely linked with interest in sexual variation, this (also) could affect the discriminative ability of the NPAS among heterosexual women in our dataset especially. (iii) Research into sexual fantasies show that women compared with men more often have fantasies about being dominated.35, 36 Accordingly, the discriminatory ability of items focusing on domination could be weakened among women because of the relative commonplace occurrence of such themes in their sexual fantasies. As a potential remedy, we suggest that future cross-cultural explorations of the NPAS include the testing of additional non-mainstream items and/or different wording of these problematic themes among non-exclusively heterosexual men and heterosexual women.

When considering the reported results, several study limitations need to be taken into account. The study used a non-probability sampling strategy, which could limit the generalization of the study findings, because our sample was biased toward more educated and affluent participants. Furthermore, only self-report–based measures and evaluations were used in the study. Although such reports are standard in sex research, they might not always be accurate, because they introduce the possibility of systematic biases.37 In addition, self-evaluations of sexual interests and sexual fantasies associated with SEM-related experiences were assessed using 1-item indicators, which might not adequately capture the complexity of these concepts (see also 38). In this light, the associated findings should be considered preliminary.

Setting these limitations aside, the study offers 1st insights into patterns of average levels of sexual arousal to various types of SEM across SEM users characterized by self-reported patterns of sexual arousal to non-mainstream vs mainstream SEM. In this study, non-mainstream SEM group participants generally used more SEM and self-reported significantly higher levels of sexual arousal to SEM compared with mainstream SEM group participants. Further, non-mainstream group participants showed non-fixated SEM arousability and produced non-negative judgments about their sexual interests and fantasies. Moreover, the study shows that the recently developed NPAS6, 7 generally showed good validity and predictive utility for men and non-exclusively heterosexual women, making it a reliable tool for researchers and clinicians working with SEM and/or sexual arousal in these user groups.

Statement of authorship

Category 1

- (a)

Conception and Design

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

- (b)

Acquisition of Data

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

- (c)

Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

Category 2

- (a)

Drafting the Article

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

- (b)

Revising It for Intellectual Content

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

Category 3

- (a)

Final Approval of the Completed Article

- Gert Martin Hald; Aleksandar Stulhofer; Theis Lange

References

- Chivers, M.L., Rieger, G., Latty, E. et al. A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychol Sci. 2004; 15: 736–744

- Sarlo, M. and Buodo, G. To each its own? Gender differences in affective, autonomic, and behavioral responses to same-sex and opposite-sex visual sexual stimuli. Physiol Behav. 2017; 171: 249–255

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (1)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (89)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (22)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (3)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (229)

- Rupp, H.A. and Wallen, K. Sex differences in response to visual sexual stimuli: a review. Arch Sex Behav. 2008; 37: 206–218

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- View in Article

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | Scopus (29)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (19)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (11)

- View in Article

- | Abstract

- | Full Text

- | Full Text PDF

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (6)

- View in Article

- | Abstract

- | Full Text

- | Full Text PDF

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (22)

- View in Article

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- View in Article

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | Scopus (1672)

- View in Article

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (236)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- View in Article

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (7)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (3)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (7)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- | Scopus (0)

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | PubMed

- View in Article

- | Crossref

- | Scopus (40)

- Huberman, J.S. and Chivers, M.L. Examining gender specificity of sexual response with concurrent thermography and plethysmography. Psychophysiology. 2015; 52: 1382–1395

- Rupp, H.A. and Wallen, K. Sex-specific content preferences for visual sexual stimuli. Arch Sex Behav. 2009; 38: 417–426

- Hald, G.M. and Štulhofer, A. What types of pornography do people use and do they cluster? Assessing types and categories of pornography consumption in a large-scale online sample. J Sex Res. 2016; 53: 849–859

- Hald, G.M. and Štulhofer, A. Authors correction letter. J Sex Res. 2016; 53: 894

- Knack, N.M., Murphy, L., Ranger, R. et al. Assessment of female sexual arousal in forensic populations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015; 17: 1–8

- Seto, M.C. and Lalumiere, M.L. What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010; 136: 526–575

- Malamuth NM, Hald GM. The confluence model of sexual aggression. In Boer DP. (Ed.) The Wiley Handbook on the Theories, Assessment and Treatment of Sexual Offending: Vol I. Theories pp. 53-71. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Lalumiere, M.L., Quinsey, V.L., Harris, G.T. et al. Are rapists differentially aroused by coercive sex in phallometric assessments?. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003; 989: 211–224

- Quinsey, V.L. and Lalumiere, M.L. Assessment of sexual offenders against children. 1 ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA; 2001

- Hald, G.M., Seaman, C., and Linz, D. Sexuality and pornography. in: APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, volume 2 2. Contextual approaches. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC; 2014: 3–35

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009; 135: 707–730

- Herek, G.M. Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: a conceptual framework. in: D.A. Hope (Ed.) Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities. Springer, New York; 2009: 65–111

- Jahnke, S., Imhoff, R., and Hoyer, J. Stigmatization of people with pedophilia: two comparative surveys. Arch Sex Behav. 2014; 44: 21–34

- Jahnke, S., Schmidt, A.F., Geradt, M. et al. Stigma-related stress and its correlates among men with pedophilic sexual interests. Arch Sex Behav. 2015; 44: 2173–2187

- Ahlers, C.J., Schaefer, G.A., Mundt, I.A. et al. How unusual are the contents of paraphilias? Paraphilia-associated sexual arousal patterns in a community-based sample of men. J Sex Med. 2011; 8: 1362–1370

- Joyal, C.C. and Carpentier, J. The prevalence of paraphilic interests and behaviors in the general population: a provincial survey. J Sex Res. 2017; 54: 161–171

- Joyal, C.C., Cossette, A., and Lapierre, V. What exactly is an unusual sexual fantasy?. J Sex Med. 2015; 12: 328–340

- Štulhofer, A., Buško, V., and Brouillard, P. The new sexual satisfaction scale and its short form. in: T.D. Fisher, C.M. Davis, W.L. Yarber, (Eds.) Handbook of sexuality-related measures. 3rd ed. Routledge, New York; 2011: 530–532

- Hald, G.M. Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2006; 35: 577–585

- Ogas, O. and Gaddam, S. A billion wicked thoughts: what the Internet tells us about sexual relationships. Penguin Publishing Group, New York; 2011

- Ogas, O. and Gaddam, S. A billion wicked thoughts: what the world’s largest experiment reveals about human desire. Penguin, New York; 2011

- Fraley, C. and Raftery, A.E. Model-based clustering, discriminant analysis, and density estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 2002; 97: 611–631

- Fraley, C., Raftery, A.E., and Murphy, T.B. Mclust version 4 for R: normal mixture modeling for model-based clustering, classification, and density estimation. Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle; 2012

- Chivers, M.L., Seto, M.C., Lalumiere, M.L. et al. Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: a meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2010; 39: 5–56

- Streiner, D.L. and Caimey, J. What’s under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Can J Psychiatry. 2007; 52: 121–128

- Laws, D.R. and Marshall, W.L. Masturbatory reconditioning with sexual deviates: an evaluative review. Adv Behav Res Ther. 1991; 13: 13–25

- Marshall, W.L., Marshall, L.E., and Serran, G.A. Strategies in the treatment of paraphilias: a critical review. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2006; 17: 162–182

- McManus, M.A., Hargreaves, P., Rainbow, L. et al. Paraphilias: definition, diagnosis and treatment. F1000Prime Rep. 2013; 5: 36

- Seigfried-Spellar, K.C. and Rogers, M.K. Does deviant pornography use follow a Guttman-like progression?. Comput Hum Behav. 2013; 29: 1997–2003

- Rullo, J.E., Strassberg, D.S., and Miner, M.H. Gender-specificity in sexual interest in bisexual men and women. Arch Sex Behav. 2014; 44: 1449–1457

- Dawson, S.J., Bannerman, B.A., and Lalumiere, M.L. Paraphilic interests an examination of sex differences in a nonclinical sample. Sex Abuse. 2016; 28: 20–45

- Hawley, P.H. and Hensley, W.A. Social dominance and forceful submission fantasies: feminine pathology or power?. J Sex Res. 2009; 46: 568–585

- Leitenberg, H. and Henning, K. Sexual fantasy. Psychological bulletin. 1995; 117: 469–496

- Graham, C.A., Catania, J.A., Brand, R. et al. Recalling sexual behavior: a methodological analysis of memory recall bias via interview using the diary as the gold standard. J Sex Res. 2003; 40: 325–332

- Wilson, G.D. Measurement of sex fantasy. Sex Marital Ther. 1988; 3: 45–55