Syst Rev. 2020 Dec 6;9(1):283.

doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01541-0.

- PMID: 33280603

- DOI: 10.1186/s13643-020-01541-0

Ayẹwo Imọlẹroye iwọn didun 9, Nkan nọmba: 283 (2020).

áljẹbrà

Background

Young people’s use of pornography and participation in sexting are commonly viewed as harmful behaviours. This paper reports findings from a ‘review of reviews’, which aimed to systematically identify and synthesise the evidence on pornography and sexting amongst young people. Here, we focus specifically on the evidence relating to young people’s use of pornography; involvement in sexting; and their beliefs, attitudes, behaviours and wellbeing to better understand potential harms and benefits, and identify where future research is required.

awọn ọna

We searched five health and social science databases; searches for grey literature were also performed. Review quality was assessed and findings synthesised narratively.

awọn esi

Awọn atunwo mọkanla ti pipo ati/tabi awọn ijinlẹ agbara ni o wa pẹlu. Ibasepo kan jẹ idanimọ laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati awọn iwa ibalopọ iyọọda diẹ sii. Ẹgbẹ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati awọn igbagbọ ibalopo ti o ni okun sii ni a tun royin, ṣugbọn kii ṣe deede. Bakanna, ẹri aisedede ti ajọṣepọ kan laarin lilo aworan iwokuwo ati sexting ati ihuwasi ibalopọ jẹ idanimọ. Lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ti ni nkan ṣe pẹlu ọpọlọpọ awọn iwa-ipa ibalopo, ifinran ati ikọlu, ṣugbọn ibatan naa han eka. Awọn ọmọbirin, ni pataki, le ni iriri ipaniyan ati titẹ lati ṣe alabapin ninu sexting ati jiya awọn abajade odi diẹ sii ju awọn ọmọkunrin ti sexts ba di gbangba. Awọn aaye to dara si sexting ni a royin, ni pataki ni ibatan si awọn ibatan ti ara ẹni ti awọn ọdọ.

ipinnu

A ṣe idanimọ ẹri lati awọn atunwo ti o yatọ didara ti o so lilo aworan iwokuwo ati sexting laarin awọn ọdọ si awọn igbagbọ, awọn ihuwasi ati awọn ihuwasi kan pato. Bibẹẹkọ, ẹri nigbagbogbo jẹ aisedede ati pupọ julọ ti o wa lati awọn iwadii akiyesi nipa lilo apẹrẹ apakan-agbelebu, eyiti o yago fun idasile ibatan idi eyikeyi. Awọn idiwọn ilana miiran ati awọn ela ẹri ni a mọ. Awọn ijinlẹ pipo lile diẹ sii ati lilo nla ti awọn ọna agbara ni a nilo.

Background

Ni ọdun mẹwa to kọja, ọpọlọpọ awọn atunyẹwo ominira ti wa ni ipo ijọba UK sinu ibalopọ ti igba ewe ati aabo awọn ọdọ lori ayelujara ati lori awọn media oni-nọmba miiran (fun apẹẹrẹ, Byron [1]; Papadopoulos [2]; Bailey [3]). Awọn ijabọ irufẹ tun ti ṣe atẹjade ni awọn orilẹ-ede miiran pẹlu Australia [4,5,6]; France [7]; and the USA [8]. Lori ipilẹ iwulo ti a ro pe lati daabobo awọn ọmọde lati awọn ohun elo ibalopọ lori ayelujara, ijọba UK wa ninu Ofin Aje Digital [9], a requirement for pornographic websites to implement age verification checks. However, following several delays in implementation, it was announced in autumn 2019 that checks would not be introduced [10]. Instead, the objectives of the Digital Economy Act in relation to preventing children’s exposure to online pornography are to be met through a new regulatory framework set out in the Online Harms White paper [11]. This White paper proposes establishing a statutory duty of care on relevant companies to improve online safety and tackle harmful activity, which will be enforced by an independent regulator [11].

Nigbagbogbo a ti daba pe wiwo awọn ọmọde ati awọn ọdọ ti awọn aworan iwokuwo yori si ipalara (fun apẹẹrẹ, Ikun-omi [12]; Ounjẹ ounjẹ [13]). In addition, sexting (a portmanteau of ‘sex’ and ‘texting’) is often framed within a discourse of deviance and the activity viewed as a high-risk behaviour for young people [14]. Diẹ ninu awọn ipalara ti a daba pẹlu iwa-ipa ibalopo ati ifipabanilopo lati ṣe awọn iṣe ti o ni ibatan ibalopọ, botilẹjẹpe ohun ti o tumọ si nipa ipalara ko ti sọ nigbagbogbo ni kedere.

This paper reports findings from a ‘review of reviews’ commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in England, which aimed to systematically identify and synthesise the evidence on pornography and sexting amongst children and young people. Given the wide scope, a ‘review of reviews’ (RoR) was considered the most appropriate method. RoRs identify, appraise and synthesise findings from existing reviews in a transparent way and can also highlight the absence of evidence [15,16,17,18,19]. Here, we focus specifically on the evidence relating to young people’s use of pornography; involvement in sexting; and their beliefs, attitudes, behaviours and wellbeing, to better understand potential harms and benefits, and to identify where future research is required.

ọna

A ṣawari awọn apoti isura infomesonu itanna marun ni lilo ọpọlọpọ awọn ọrọ koko-ọrọ ati awọn itumọ-ọrọ, pẹlu “awọn aworan iwokuwo”, “akoonu ti ibalopọ ibalopo” ati “sexting”, ni idapo pẹlu àlẹmọ wiwa fun awọn atunwo eto.Akọsilẹ ọrọ 1. Ilana wiwa ni kikun wa bi faili afikun (Faili afikun 1). Awọn apoti isura infomesonu wọnyi ti wa titi di Oṣu Kẹjọ / Oṣu Kẹsan 2018: Atọka Imọ-jinlẹ Awujọ ti a lo & Awọn Abstracts (ASSIA), MEDLINE ati MEDLINE ni Ilana, PsycINFO, Scopus ati Atọka Imọ-jinlẹ Awujọ. Ko si awọn ihamọ ti a gbe sori ọjọ ti atẹjade tabi ipo agbegbe. Ni afikun, awọn iwadii afikun ni a ṣe ti awọn oju opo wẹẹbu ti awọn ajo pataki, pẹlu Komisona Awọn ọmọde fun England; National Society for the Care and Protection of Children (NSPCC) ati aaye ayelujara ti ijọba UK. A wa awọn iwe grẹy miiran nipa lilo iṣẹ wiwa ilọsiwaju ti Google.

Akọle ati áljẹbrà ti awọn igbasilẹ, ati awọn iwe-kikun ni a ṣe ayẹwo nipasẹ awọn oluyẹwo meji ni ominira. Awọn awari ti a royin ninu iwe lọwọlọwọ da lori awọn atunwo ti o pade awọn ibeere wọnyi:

- Fojusi lori lilo awọn ọmọde ati awọn ọdọ (sibẹsibẹ asọye) lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo, sexting tabi awọn mejeeji. Eyikeyi iru aworan iwokuwo (titẹ tabi wiwo) ni a ka pe o yẹ.

- Reported findings related to pornography and sexting and their relationship to young people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviours or wellbeing.

- Awọn ọna atunyẹwo eto ti a lo, eyiti o nilo awọn onkọwe lati ni, bi o kere ju: wa o kere ju awọn orisun meji, ọkan ninu eyiti o gbọdọ jẹ data ti a npè ni; ifisi ifisi / iyasoto iyasọtọ ti o bo awọn paati atunyẹwo bọtini; o si pese akojọpọ awọn awari. Eyi le jẹ iṣelọpọ eekadẹri ni irisi oniwadi-meta tabi akopọ itan ti awọn awari lati awọn iwadii ti o wa. Awọn atunwo ko yẹ fun ifisi ti awọn onkọwe ba ṣapejuwe nirọrun kọọkan kọọkan pẹlu iwadi pẹlu ko si igbiyanju ti a ṣe lati mu awọn awari papọ lori abajade kanna lati awọn iwadii pupọ.

Awọn atunyẹwo nilo lati ni idojukọ akọkọ lori aworan iwokuwo tabi sexting ati awọn ọdọ ati pe o le pẹlu awọn iwadii akọkọ ti eyikeyi apẹrẹ (ipo ati / tabi agbara). Awọn atunwo ni a yọkuro ti wọn ba dojukọ nipataki lori akoonu ibalopọ ninu awọn media olokiki ti kii ṣe onihoho gẹgẹbi awọn eto tẹlifisiọnu, awọn ere fidio tabi awọn fidio orin. Sexting ti ni imọran ni fifẹ bi fifiranṣẹ tabi gbigba awọn fọto ti o fojuhan ibalopọ tabi awọn ifiranṣẹ nipasẹ foonu alagbeka tabi awọn ẹrọ media miiran.

Data were extracted from each review on key characteristics including review methods, population(s) and outcomes. Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer.

Each review was critically appraised according to modified Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) criteria [20]. Review quality was assessed by one reviewer and checked by another. The critical appraisal process was used to inform judgements about potential sources of bias and threats to the validity and reliability of findings reported across reviews.

Awọn awari ni a ṣepọ ni itan-akọọlẹ kọja awọn atunwo ati ṣe afiwe ati iyatọ, nibiti o yẹ. Lakoko ilana iṣelọpọ, gbogbo data ti a fa jade lati awọn atunwo ti o jọmọ ẹka gbooro kanna tabi akori (fun apẹẹrẹ ihuwasi ibalopọ, awọn ihuwasi ibalopọ) ni a mu papọ ati awọn ibajọra ati awọn iyatọ ninu awọn awari ti a damọ mejeeji kọja awọn atunwo ati kọja awọn iwadii laarin awọn atunwo. Akopọ ijuwe ti awọn awari akọkọ ti a royin ninu awọn atunwo lẹhinna ṣejade. Awọn awari lati awọn ẹkọ pipo ati ti agbara ni a ṣe akojọpọ lọtọ labẹ akọle koko ti o yẹ. A ko ṣe awọn arosinu lakoko ilana iṣelọpọ nipa boya awọn abajade kan pato jẹ ipalara tabi rara. Ọrọ awọn ọdọ ni a lo ni apakan atẹle lati bo mejeeji awọn ọdọ ati awọn ọmọde. A ko forukọsilẹ ilana kan fun atunyẹwo yii lori PROSPERO nitori awọn idiwọ akoko, ṣugbọn a ṣe agbejade kukuru kan ti iṣẹ akanṣe eyiti DHSC fọwọsi. Eyi ṣeto idojukọ fun atunyẹwo, awọn ọna lati lo ati iṣeto akoko fun iṣẹ naa.

awọn esi

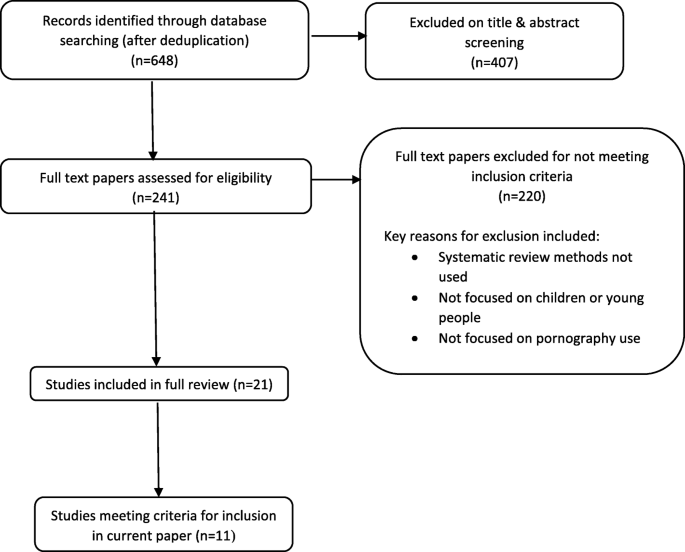

After deduplication, 648 titles and abstracts and 241 full-text papers were screened. Eleven reviews met the inclusion criteria stated above. The flow of the literature through the review is shown in Fig. 1.

Description of reviews

Of the 11 reviews, three focused on pornography [21,22,23]; seven focused on sextingAkọsilẹ ọrọ 2 [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]; ati atunyẹwo kan ti koju mejeeji aworan iwokuwo ati sexting [31]. Key characteristics of the 11 reviews are provided in Table 1.

Awọn atunwo meji royin awọn awari didara nikan [26, 27]. Five reviews reported quantitative findings only [23, 24, 29,30,31], and four reported findings from both types of primary study [21, 22, 25, 28]. One review reported solely on findings from longitudinal studies [23]. Awọn atunwo mẹjọ pẹlu boya awọn iwadi-apakan-agbelebu nikan tabi mejeeji apakan-agbelebu ati iwadii gigun [21, 22, 24, 25, 28,29,30,31]. Kọja awọn atunwo, ọpọlọpọ awọn ijinlẹ jẹ apakan-agbelebu ati data ti a gba ni lilo awọn ọna bii awọn iwadii ti o da lori ibeere, awọn ifọrọwanilẹnuwo ọkan-si-ọkan ati awọn ẹgbẹ idojukọ.

Data in three reviews were synthesised statistically using meta-analysis [29,30,31] ati atunyẹwo kan ti o ṣe ilana iṣelọpọ agbara-meta-ethnographic [26]. Other reviews reported a narrative synthesis of findings. Across the reviews, most included studies appeared to originate from the USA and Europe (mainly the Netherlands, Sweden and Belgium), but information about country of origin was not reported systematically.

Lapapọ, awọn atunwo to wa pẹlu idojukọ koko-ọrọ kanna jẹ iru ni awọn ofin ti iwọn ati awọn ibeere ifisi. Awọn ọjọ atẹjade ti awọn iwadi ti o wa ninu mẹjọ ti awọn atunyẹwo 11 wa laarin 2008 ati 2016 [23, 24, 26,27,28,29,30,31]. The population of interest for every review included children ranging in age from pre-teens to 18 years, but there was variation between reviews in terms of the upper age limit, which is discussed further in the limitations section. Other differences between reviews were noted: In terms of pornography, Watchirs Smith et al. [31] lojutu lori ifihan si akoonu lori awọn oju opo wẹẹbu ibalopọ / awọn aworan iwokuwo ti o da lori intanẹẹti. Ni afikun, mejeeji Handschuh et al. [30] and Cooper et al. [25] lojutu lori fifiranṣẹ awọn sexts ni idakeji si gbigba wọn.

Horvath et al. [21] described their review as a ‘rapid evidence assessment’ and included not only academic and non-academic primary research but also ‘reviews’ and meta-analyses, policy documents and other ‘reports’. Similarly, the eligibility criteria used by Cooper et al. [25] allowed for the inclusion of ‘non-empirical research discussions’ (p.707) as well as primary studies. Across reviews, several publications were linked to the same research study. For example, Koletić [23] included 20 papers that were linked to nine different research studies. In addition, Peter and Valkenburg [22] royin pe ọpọlọpọ awọn iwadi / awọn iwe ti lo apẹẹrẹ data kanna.

Ikọja pupọ wa ninu awọn ijinlẹ akọkọ ti o wa pẹlu awọn atunwo, eyiti kii ṣe airotẹlẹ fun ibajọra ni iwọn laarin awọn atunwo. Fún àpẹrẹ, àwọn àyẹ̀wò mẹ́ta ṣàkópọ̀ dátà ìpilẹ̀ ìtàn nípa ìbáṣepọ̀ láàrin sexting àti ìṣesí ìbálòpọ̀, àti láàrín sexting àti ìhùwàsí ewu ìlera ìbálòpọ̀ gẹ́gẹ́ bí lílo nǹkan. Barrense-Dias et al. [28] tọka si awọn iwe oriṣiriṣi meje ti o koju awọn ibatan wọnyi, Van Ouytsel et al. [24] cited five, and three papers were common to both reviews. All five of the papers cited by Van Ouytsel et al. and four by Barrense-Dias et al. were also included by Cooper et al. [25]. Reviews by Horvath et al. [21, Peter ati Valkenburg [22] and Koletić [23] had four studies in common that addressed pornography use and permissive attitudes and gender-stereotypical sexual beliefs.

Review quality

Awọn igbelewọn ti awọn atunwo lodi si awọn ibeere DARE ti a yipada ni a fihan ni Tabili 2. All reviews were rated as being adequate for scope of literature searching and reporting of inclusion/exclusion criteria. In nine reviews, searches were conducted of at least three databases [21, 23,24,25,26, 28,29,30,31]. Ni awọn atunwo meji, awọn iwadii ni a ṣe ni lilo nọmba data data ti o kere ju, ṣugbọn a ṣe afikun nipasẹ lilo awọn orisun miiran gẹgẹbi iṣayẹwo atokọ itọkasi tabi wiwa intanẹẹti [22, 27]. In two reviews, only the single word, ‘sexting’ was used as a search term [24, 29]. All reviews reported eligibility criteria covering all or most of the following key review components: population; behaviour (i.e. pornography, sexting or both); issue or outcomes of interest; and publication/study type.

The extent to which authors synthesised findings was variable but adequate in all reviews. Three of the reviews that synthesised results narratively were rated higher on this criterion as they provided a synthesis that was more detailed and comprehensive in drawing together and reporting findings from multiple studies [22, 24, 28].

Reviews were also assessed according to two additional criteria: the reporting of study details, and whether an evaluation of the methodological quality of included studies was reported. Eight reviews provided details of included studies in the form of a table of characteristics that reported a range of relevant information about the population sample, study design, variables and/or outcomes of interest/key findings [22,23,24, 26, 28,29,30,31]. Awọn atunyẹwo mẹta miiran pese awọn alaye diẹ nipa awọn ẹkọ ti o wa pẹlu [21, 25, 27].

Ninu awọn atunwo mẹrin, diẹ ninu iru igbelewọn didara ni a royin [21, 27, 30, 31]. Ni afikun, Peter ati Valkenburg [22] ko ṣe iṣiro didara ti awọn ẹkọ-ẹkọ kọọkan, ṣugbọn wọn ṣe ijabọ imọran pataki ti awọn awari lati inu atunyẹwo wọn, eyiti o wa pẹlu idamu aiṣedeede lati awọn apẹrẹ iwadi ati awọn ọna ayẹwo. Wilkinson et al. [26] royin laisi awọn iwe lori ipilẹ didara ilana kekere ṣugbọn ko sọ ni gbangba pe a ti ṣe igbelewọn didara kan. Horvath et al. [21] reported placing less emphasis in the synthesis on studies rated as ‘lower quality’ based on a modified ‘Weight of Evidence’ assessment [32].

It can be seen from Table 2 that two reviews (Handschuh et al. [30] ati Watchirs Smith et al. [31]) were assessed as meeting all five criteria. Five reviews (Van Ouytsel et al. [24]; Peter ati Valkenburg22]; Barrense-Dias et al. [28]; Kosenko et al. [29] and Wilkinson [26]) met four criteria, including reporting a higher quality narrative synthesis of findings or a meta-analysis.

Ijabọ ti awọn ọna atunyẹwo ko pe ni gbogbo awọn atunwo, eyiti o ṣe idiwọ igbelewọn ti igbẹkẹle gbogbogbo tabi agbara fun ojuṣaaju. Fun apẹẹrẹ, pupọ julọ awọn atunyẹwo ko pese alaye nipa nọmba awọn oluyẹwo ti o ni ipa ninu awọn ipinnu iboju tabi isediwon data.

Sexual attitudes and beliefs

Evidence was consistent across four reviews for a relationship between young people’s viewing of sexually explicit material, and stronger permissive sexual attitudes [21,22,23, 31]. ‘Permissive sexual attitudes’ is a term used across reviews, but not always defined. Peter and Valkenburg [22] lo o lati se apejuwe rere iwa si àjọsọpọ ibalopo , ojo melo ita ti a romantic ibasepo.

Awọn atunyẹwo mẹrin ṣe ijabọ ẹri ti ajọṣepọ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati awọn igbagbọ ibalopo ti o ni okun sii-stereotypical, pẹlu wiwo awọn obinrin bi awọn nkan ibalopọ, ati awọn ihuwasi ilọsiwaju ti o dinku si awọn ipa abo.21,22,23, 31]. However, evidence for a relationship between pornography and gender-stereotypical sexual beliefs was not consistently identified. One longitudinal study included in three reviews found no association between frequency of viewing internet pornography and gender-stereotypical sexual beliefs [21,22,23].

Evidence was reported across three reviews suggesting a relationship between pornography use and a range of other sexual attitudes and beliefs, including sexual uncertainty; sexual preoccupancy; sexual satisfaction/dissatisfaction; unrealistic beliefs/attitudes about sex and ‘maladaptive’ attitudes towards relationships [21,22,23]. Awọn awari wọnyi nigbagbogbo da lori awọn iwadii kan tabi meji nikan, pẹlu agbekọja kọja awọn atunwo.

Sexual activity and sexual practices

Ẹri lati awọn iwadii gigun ati awọn abala-agbelebu ti a royin ninu awọn atunyẹwo mẹrin daba ajọṣepọ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati iṣeeṣe ti o pọ si ti ikopa ninu ibalopọ ati awọn iṣe ibalopọ miiran gẹgẹbi ẹnu tabi ibalopọ.21,22,23, 31]. Gender and pubertal status were identified as moderators of the association between pornography use and initiating sexual intercourse in one review [22]. Awọn iwadi tun ṣe ijabọ kọja awọn atunwo ti ko rii ibatan laarin lilo aworan iwokuwo ati awọn oriṣi awọn iṣe ibalopọ ati ihuwasi, pẹlu ajọṣepọ ṣaaju ọjọ-ori 15, tabi awọn iwadii ti rii awọn ẹgbẹ ti ko ni ibamu [21,22,23, 31].

An association between pornography use and engaging in casual sex or sex with multiple partners was reported in three reviews [21, 22, 31]. Bibẹẹkọ, ajọṣepọ kan laarin ibalopọ lasan ati lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo nikan ni a rii fun awọn ọdọ obinrin ni ọkan ninu awọn ẹkọ ti o wa pẹlu Peter ati Valkenburg.22]. Ni afikun, iwadi kan ti o royin kọja awọn atunyẹwo mẹta ko rii ajọṣepọ pataki laarin lilo aworan iwokuwo ati nini nọmba ti o ga julọ ti awọn alabaṣepọ ibalopo [21, 22, 31].

Ẹri ti o so awọn aworan iwokuwo pọ mọ eewu ibalopọ ninu awọn ọdọ ko ni ibamu. Awọn atunyẹwo mẹta ṣe ijabọ ajọṣepọ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati ihuwasi ibalopo 'eewu', pẹlu nini ibalopọ ti ko ni aabo ati lilo oogun / oti lakoko ibalopọ [21, 22, 31]. However, another study included in two reviews failed to identify an association between pornography use and engaging in unprotected casual sex [22, 23].

Mejeeji Horvath et al. [21] and Peter and Valkenburg [22] included qualitative studies that suggested young people may learn sexual practices and scripts for sexual performance from pornography, which can influence their expectations and behaviour. Pornography was also seen as a standard by which to judge sexual performance and body ideals in some qualitative studies. Evidence reported by Horvath et al. [21] fihan pe diẹ ninu awọn ọdọ wo awọn aworan iwokuwo bi orisun rere ti imọ-ibalopo, awọn imọran, awọn ọgbọn ati igbẹkẹle.

An association between sexting and engaging in various types of sexual activity was identified in six reviews [24, 25, 28,29,30,31]. A recent meta-analysis of six studies [30] ri pe awọn aidọgba ti iroyin boya ti o ti kọja tabi lọwọlọwọ ibalopo aṣayan iṣẹ-ṣiṣe wà to mefa ni igba ti o ga fun awọn ọdọ ti o rán sexts, akawe pẹlu awon ti ko (OR 6.3, 95% CI: 4.9 to 8.1). Onínọmbà meta iṣaaju [31] ri pe sexting ni nkan ṣe pẹlu o ṣeeṣe ti o pọ si ti nini ibalopo nigbagbogbo (obo nikan tabi abẹ, furo tabi ẹnu) (OR 5.58, 95% CI: 4.46 si 6.71, awọn iwadii marun) ati pẹlu iṣẹ ṣiṣe ibalopọ laipẹ (OR 4.79). , 95% CI: 3.55 si 6.04, awọn ẹkọ meji). Onínọmbà meta miiran ti awọn iwadii 10 [29], royin ajọṣepọ kan laarin sexting ati ikopa ninu 'iṣe ibalopọ gbogbogbo' (r = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.23 to 0.46). There was notable overlap in the primary studies across the meta-analyses by Watchirs Smith et al. [31], Kosenko et al. [29] ati Handschuh et al. [30]. Five out of the 10 studies included in the meta-analysis by Kosenko et al. had been included in the earlier meta-analysis by Watchirs Smith et al. that was focused on having ‘ever’ engaged in intercourse. The most recent meta-analysis by Handschuh et al. included only one study that was not in the meta-analysis by Kosenko et al. In addition, the same three studies were included in all three meta-analyses.

Awọn atunyẹwo mẹrin ṣe idanimọ ajọṣepọ kan laarin sexting ati nini nọmba ti o ga julọ ti awọn alabaṣiṣẹpọ ibalopo [29] tabi ọpọ awọn alabaṣepọ, lori orisirisi awọn akoko akoko [24, 25, 31]. However, in one of the studies reported by Van Ouytsel et al. [24] ẹgbẹ kan wa laarin awọn ọmọbirin nikan. Kosenko et al. [29] royin pe ajọṣepọ laarin sexting ati nọmba awọn alabaṣepọ jẹ kekere (r = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.16 si 0.23, awọn ẹkọ meje). Watchirs Smith et al. [31] found that the likelihood of having multiple sexual partners in the past 3 to 12 months was approximately three times higher amongst young people who sexted compared with those who did not (OR 2.79, 95% CI: 1.95 to 3.63; two studies).

Ẹri aisedede fun ajọṣepọ kan laarin sexting ati awọn ihuwasi ibalopo 'eewu' ni a royin kọja awọn atunwo marun.24, 25, 28, 29, 31]. Kosenko et al. [29] ri ajọṣepọ kan laarin sexting ati ikopa ninu iṣẹ-ibalopo ti ko ni aabo lati inu itupalẹ akojọpọ ti awọn iwadii mẹsan, ṣugbọn iwọn ibatan jẹ kekere (r = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.23). In contrast, another meta-analysis of two studies [31] found no association between sexting and engaging in condomless anal intercourse in the past one or two months (OR 1.53, 95% CI: 0.81 to 2.25). Three reviews [24, 25, 31] royin pe sexting ni nkan ṣe pẹlu lilo oti tabi awọn oogun miiran ṣaaju / lakoko ibalopọ (Watchirs Smith, OR 2.65, 95% CI: 1.99 si 3.32; awọn ẹkọ meji) [31].

Awọn ihuwasi eewu miiran

An association between sexting and substance use (alcohol, tobacco, marijuana and other illicit drugs) was reported in three reviews [24, 25, 28]. Ni afikun, iwadi kan ti a royin nipasẹ Barrense-Dias et al. [28] ri ohun sepo laarin sexting ati ti ara ija laarin omokunrin. Awọn onkọwe kanna tun ṣe idanimọ ẹri lati inu iwadi miiran ti ibatan laarin sexting ati awọn ihuwasi “eewu” miiran gẹgẹbi gbigbe ati gbigba sinu wahala pẹlu awọn olukọ tabi ọlọpa. Bakanna, iwadi kan ti o wa nipasẹ Van Ouytsel et al. [24] royin wipe ile-iwe omo ile ti o sexted wà diẹ seese lati ti npe ni 'delinquency'. ‘Aiṣedeede’ oniyipada jẹ asọye nipasẹ awọn oludahun’ ifarapa tẹlẹ ninu awọn ihuwasi mẹsan ti awọn onkọwe iwadi wo bi awọn iṣe aitọ, gẹgẹbi jija, gbigbe, mimu mimu ati mimu. Ẹri ti ọna asopọ laarin awọn aworan iwokuwo ati fifọ ofin tabi ihuwasi aitọ ni a royin ni awọn atunwo meji [21, 22]. Furthermore, both Horvath et al. [21] and Peter and Valkenburg [22] wa pẹlu iwadii ẹyọkan kanna ti o ṣe idanimọ ajọṣepọ laarin awọn aworan iwokuwo ati lilo nkan.

Ibalopo iwa-ipa ati ifinran

An association between exposure to sexually explicit media and various forms of sexual violence and aggression has been found in both longitudinal and cross-sectional research. Three reviews identified an association between pornography use and the perpetration of sexual harassment or sexually aggressive behaviour, including forced sexual activity [21,22,23]. Ninu iwadi kan ti o royin kọja awọn atunyẹwo mẹta, ọna asopọ laarin iwa-ipa ibalokanjẹ ati wiwo awọn media ti o fojuhan ni a rii fun awọn ọmọkunrin nikan. Iwadi miiran ti o wa nipasẹ Horvath et al. [21] royin awọn awari ti o ni iyanju pe awọn aworan iwokuwo nikan ni nkan ṣe pẹlu iwa-ipa ibalopo ni awọn ọdọ ti o ni asọtẹlẹ fun ihuwasi ibalopọ ibinu. Pẹlupẹlu, iwadi gigun kan ti o wa ninu gbogbo awọn atunyẹwo mẹta ti ri ajọṣepọ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati iwa-ipa ibalopo tabi ikọlu, ṣugbọn nikan nigbati a ba wo awọn ohun elo iwa-ipa. Peter ati Valkenburg22] also reported evidence from one study that found an association between sexual violence or harassment and the use of pornographic magazines and comics, but identified no association with the use of pornographic films and videos. In two studies reviewed by Horvath et al. [21], lilo igbagbogbo ti awọn aworan iwokuwo ati / tabi wiwo awọn aworan iwokuwo iwa-ipa ni o wọpọ julọ laarin awọn ọmọ ile-iwe giga akọ ati abo ti o ti ni ipa ni ihuwasi ifipabanilopo ni akawe pẹlu awọn ẹlẹgbẹ ti ko ni.

Awọn atunwo meji royin ajọṣepọ kan laarin wiwo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati jijẹ olufaragba iwa-ipa ibalopo tabi tipatipa ibalopọ, paapaa laarin awọn ọdọbinrin [21, 22]. Three reviews reported findings from one study that found sexting adolescents were more likely to ever have been forced to have sex, and to have been subjected to physical violence by their partner in the previous year, than adolescents who had not engaged in sexting [24, 25, 31]. Cooper et al. [25] siwaju royin ajọṣepọ kan laarin gbigba sext ati iriri iwa-ipa interpersonal lati inu iwadi kan ti awọn ọmọ ile-iwe giga.

Coercion, bullying and harassment

Three reviews reported that girls, in particular, may experience coercion and pressure to engage in sexting [25, 26, 28]. An association was also identified between bullying, cyberbullying or harassment and sexting [24, 25, 28]. For example, one cross-sectional study included by Barrense-Dias et al. [28] found that adolescent girls who had been a victim of cyberbullying were more likely to sext. Furthermore, Cooper et al. [25] ṣe idanimọ eewu ti o tobi julọ ti awọn oriṣiriṣi oriṣi ti ijiya cyber fun awọn obinrin ti o ṣiṣẹ ni sexting ti o da lori ikẹkọ apakan-agbelebu kan ti awọn ọmọ ile-iwe kọlẹji. Wọn tun royin awọn awari lati inu iwadi miiran ti o daba pe awọn ọdọ ti o ṣe atinuwa ni 'ifihan ibalopọ' lori intanẹẹti ni o ṣeeṣe ki mejeeji gba ati ṣe ifipabanilopo lori ayelujara.

Qualitative findings reported in four reviews suggested that girls who engaged in sexting may receive more negative treatment than boys, and also potentially experience greater judgement and reputational consequences, if images become public as a result of non-consensual sharing [25,26,27,28]. Iwadi pipo kan ti a ṣe atunyẹwo nipasẹ Cooper et al. [25] ri wipe omokunrin, ni pato, wà seese lati ni iriri ipanilaya tabi jẹ awọn olufaragba ti kii-consensual pinpin ti awọn aworan. Mejeeji Cooper et al. [25] ati Handschuh et al. [30] tun royin pe awọn obirin ni idaamu diẹ sii nipasẹ awọn ibeere si sext ju awọn ọkunrin lọ.

Opolo ilera ati alafia

Awọn ẹkọ ẹyọkan ti o royin nipasẹ Koletić [23] and Peter and Valkenburg [22] linked the use of pornography to increased body surveillance in boys. In addition, Horvath et al. [21] and Peter and Valkenburg [22] wa ninu awọn ẹkọ ti o ni agbara eyiti o rii pe awọn ọdọbirin, ni pataki, gbagbọ pe awọn aworan iwokuwo ṣe afihan apẹrẹ ara obinrin ti a ko le de, ati pe wọn ko ni ifamọra ni afiwe. Wọn tun royin rilara titẹ nipasẹ awọn ifiranṣẹ ti o jọmọ aworan ara ti a gbejade nipasẹ awọn aworan iwokuwo. Horvath et al. [21] royin ẹri aiṣedeede ti ajọṣepọ kan laarin awọn aworan iwokuwo ati ibanujẹ: ifihan si aworan iwokuwo ni ibatan si ibanujẹ ni awọn iwadii meji, ṣugbọn ẹkẹta ko rii ajọṣepọ laarin wiwa awọn ohun elo onihoho ati ibanujẹ tabi aibalẹ. Koletić [23] reported findings from a longitudinal study that found depression at baseline was associated with the compulsive use of pornography by adolescents 6 months later.

Awọn atunyẹwo mẹta royin ẹri aisedede lori ibatan laarin sexting ati ilera ọpọlọ [24, 25, 28]. Iwadi kan ti o wa nipasẹ Barrense-Dias et al. [28] identified an association between ‘psychological difficulties’ and an increased likelihood of receiving sexts and being ‘harmed’ by them. All three reviews reported evidence of a relationship between depression, or depressive symptoms and sexting. In a single study included by both Van Ouytsel et al. [24] and Cooper et al. [25], ohun sepo ti a royin laarin olukoni ni sexting ati rilara ìbànújẹ tabi ainireti fun diẹ ẹ sii ju ọsẹ meji ninu awọn ti tẹlẹ odun. A tun ṣe idanimọ ẹgbẹ kan laarin sexting ati ti ronu tabi gbiyanju igbẹmi ara ẹni ni ọdun ti tẹlẹ. Ninu iwadi kan ti a ṣe ayẹwo nipasẹ Barrense-Dias et al. [28], an association with depression was only identified for younger females. Other studies reported across the three reviews found no relationship between sexting and depression, or sexting and anxiety [24, 25, 28].

Ninu iwadi kan ti awọn olumulo intanẹẹti ọdọ 1,560 ti o wa ninu awọn atunyẹwo mẹta, idamarun ti awọn idahun ti o firanṣẹ sext kan royin ipa ẹdun ti ko dara (rilara pupọ tabi pupọju, itiju tabi bẹru) [24, 25, 28]. Also based on the findings from a single study, Barrense-Dias et al. [28] daba pe awọn ọmọbirin ati awọn ọdọ ni o ṣee ṣe diẹ sii lati jabo ibinu tabi ipalara lati sexting.

ibasepo

Awọn atunyẹwo mẹta ṣe idanimọ awọn aaye rere si sexting ni ibatan si awọn ibatan ti ara ẹni ti awọn ọdọ [25,26,27]. For example, sexting has been described by some young people as a safe medium for flirting and experimentation, as well as a safer alternative to having sex in real life. Sexting was also reported to help maintain long-distance relationships.

fanfa

Awọn awari lati awọn atunwo 11 ni a ṣajọpọ lati pese akopọ ati iṣiro ti ẹri lọwọlọwọ ni ibatan si lilo awọn ọdọ ti awọn aworan iwokuwo ati ilowosi ninu sexting, ati awọn igbagbọ, awọn ihuwasi, ihuwasi ati alafia wọn. Awọn ẹkọ lori awọn aworan iwokuwo mejeeji ati sexting nigbagbogbo ni a ti ṣe agbekalẹ laarin apẹrẹ “awọn ipa odi”, eyiti o dawọle awọn ihuwasi ibalopọ kan pato jẹ aṣoju awọn eewu tabi awọn ipalara [33]. Ninu apẹrẹ yii, ifihan si media ti ko boju mu ibalopọ ni a ka si iyanju ti o pọju si ilowosi ninu awọn ihuwasi 'ipalara' [33, 34].

RoR yii ṣe idanimọ ẹgbẹ kan laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo mejeeji ati sexting ati awọn ihuwasi ibalopọ kan. Diẹ ninu awọn ihuwasi wọnyi, gẹgẹbi ikopa ninu ibalopo lasan, ibalopo furo tabi nini nọmba ti o ga julọ ti awọn alabaṣepọ, le ni awọn ipo kan ti o gbe awọn eewu diẹ, ṣugbọn ko si ọkan ninu wọn, tabi didimu awọn ihuwasi ibalopọ iyọọda, jẹ ipalara ti ara wọn.33, 35].

Ẹri ti ajọṣepọ kan laarin awọn ihuwasi ibalopọ ati lilo aworan iwokuwo, ni pataki, nigbagbogbo jẹ aisedede laarin awọn atunwo ati kọja awọn iwadii laarin awọn atunwo. Awọn awari aisedede ni a tun royin lori ibatan laarin awọn aworan iwokuwo mejeeji ati sexting ati ilera ọpọlọ, bakanna laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati awọn igbagbọ ibalopo-stereotypical. Ibasepo laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati iwa-ipa ibalopo ati ibinu han idiju pẹlu diẹ ninu awọn iwadii ti n daba ajọṣepọ kan nikan pẹlu awọn orisun aworan iwokuwo kan, akoonu iwokuwo kan pato tabi fun awọn ọdọ ti o ni itara si ihuwasi ibinu.

Awọn ọran ti ọgbọn

Didara atunyẹwo yatọ ati pupọ julọ ni diẹ ninu awọn idiwọn bọtini, ṣugbọn gbogbo awọn mọkanla ni a gba pe o jẹ ti idiwọn pipe. Ni pataki, awọn atunyẹwo nipasẹ Horvath et al. [21] and Cooper et al. [25] ti o ni agbara pẹlu ẹri lati nọmba aimọ ti awọn atẹjade ti ko ni agbara. Fun aidaniloju nipa awọn orisun ti ẹri ti a gbekalẹ ninu awọn atunyẹwo meji wọnyi, awọn awari wọn yẹ ki o ṣe itọju pẹlu iṣọra.

Other key methodological issues were identified with reviews and the primary studies included in them. Importantly, most of the evidence on pornography and sexting is derived from observational studies using a cross-sectional design. This means it is not possible to draw conclusions about whether reported associations are a consequence or a cause of viewing pornography or engaging in sexting. For example, it could be the case that sexting encourages young people to engage in sexual activity. However, as Kosenko et al. [29] pointed out, it is equally likely that sexting is simply an activity performed by individuals who are already sexually active, and the same also holds true with regard to the viewing of pornography. Similarly, individuals who already have stronger permissive attitudes and gender-stereotypical beliefs may be more drawn to pornography.

Review authors cited the cross-sectional nature of the evidence as a significant limitation, and more prospective longitudinal research was suggested to improve understanding of the temporal relationship between pornography or sexting and a range of outcomes. Peter and Valkenburg [22] emphasised the need to include a range of potentially significant control variables in statistical analyses of longitudinal data to reduce the likelihood of confounding and obtaining spurious associations. Importantly, these authors also highlighted the fact that whilst longitudinal studies generally have greater methodological rigour than cross-sectional designs, they are still correlational in nature and do not demonstrate causality.

Fi fun agbara fun awọn ẹgbẹ apanirun nitori idamu, awọn awari lati awọn ẹkọ ti o wa tẹlẹ yẹ ki o ṣe itọju pẹlu iṣọra. Peter ati Valkenburg22] ṣe afihan iyatọ ti o pọju ni iwọn ti awọn oluwadi ti gbiyanju lati ṣatunṣe fun idamu ninu awọn ẹkọ ti o wa tẹlẹ, pẹlu diẹ ninu awọn iṣakoso nikan fun nọmba to lopin ti awọn oniyipada gẹgẹbi awọn ẹda eniyan kọọkan. O ṣeese pe awọn asọtẹlẹ ihuwasi ti a mọye ati awọn oniyipada idarudapọ pataki miiran le ma ti ni iṣakoso fun lakoko awọn itupalẹ, eyiti o ṣe opin iwọn igbẹkẹle ti o le gbe sinu awọn awari.

Ẹri daba pe akiyesi aipe ni a ti fun si awọn ifosiwewe ọrọ-ọrọ ni awọn iwadii pipo lori sexting ati awọn ọdọ. Fun apẹẹrẹ, ko si ọkan ninu awọn iwadi ti a ṣe ayẹwo nipasẹ Van Ouytsel et al. [24] ti ṣe iyatọ laarin awọn oriṣiriṣi awọn ipo ninu eyiti sexting le waye, ati pe eyi ni a mọ pe o jẹ aropin ti o pọju. Awọn abajade ti o jọmọ ibalopọ le ni ipa nipasẹ awọn nọmba oriṣiriṣi oriṣiriṣi awọn ifosiwewe pẹlu ipo ibatan ti awọn ẹni-kọọkan ti o kan ati awọn idi wọn fun sexting. Van Ouytsel et al. daba pe diẹ ninu awọn ẹgbẹ ti o royin laarin sexting ati ihuwasi le ma di otitọ lẹhin iṣakoso fun agbegbe ti sexting ti waye.

Similar studies reported inconsistent findings on the relationship between pornography and sexting and multiple outcomes of interest. Inconsistency is likely to be related, at least in part, to heterogeneity in how previous research has been operationalised. In particular, there was marked variation in the conceptualisation and definition of both sexting and pornography. For example, multiple sexting reviews [28,29,30,31] royin pe awọn iwadi yatọ ni boya idojukọ wa lori awọn ifiranṣẹ ti a firanṣẹ, gba tabi awọn mejeeji. Awọn iyatọ tun ṣe akiyesi ni awọn iru awọn ifiranṣẹ ti a ṣe iwadi, (gẹgẹbi aworan nikan, ọrọ ati awọn aworan tabi fidio), ati ninu awọn ọrọ-ọrọ ti a lo lati ṣe apejuwe akoonu ifiranṣẹ, pẹlu awọn ọrọ ti o ṣii si itumọ olukuluku. Fún àpẹrẹ, àwọn ọ̀rọ̀ pẹ̀lú 'ìbálòpọ̀', 'ìbálòpọ̀'' 'ìbálòpọ̀', 'ìbánisọ̀rọ̀', 'àkóbá', 'ìbálòpọ̀' 'fẹ́rẹ́ ìhòòhò' tàbí 'ìhòòhò ologbele'. Bakanna, awọn itumọ ti o yatọ ati awọn ọrọ-ọrọ ni a ti lo ninu awọn iwadii iwokuwo, fun apẹẹrẹ 'ohun elo ti o ni iwọn X'; 'media ti ko boju mu ibalopo'; ati 'mediased media' [23]. Such differences were seen to reflect variation between studies in the conceptualisation of pornography and specific content of interest. Review authors highlighted a failure in some studies to provide a definition or explanation of key terms. Variability was also found in other important factors such as age range, specific outcomes studied, outcome measurement and recall periods for behaviour (e.g. ever, within the last year or last 30 days). Together, these factors make comparisons between study findings, and assessing the overall evidence base, extremely difficult.

The problem of heterogeneity was highlighted in the three reviews using meta-analysis. Watchirs Smith et al. [31] stated that a pooled estimate was not calculated for the association between pornography use and sexting and several forms of sexual activity due to high statistical heterogeneity. In addition, both Kosenko et al. [29] ati Handschuh et al. [30] royin awọn ipele idaran ti ilopọ ninu awọn itupalẹ akojọpọ wọn. Handschuh et al. [30] royin ọpọlọpọ awọn itupalẹ-meta ti o ni ibatan si sexting ati iṣẹ-ibalopo: awọn awari ni a royin fun gbogbo awọn ọdọ ni idapo, ati lẹhinna fun awọn ọkunrin ati obinrin lọtọ. Awọn itupalẹ ṣe afihan orisirisi-ara lati tobi ju ti a reti lọ nipasẹ aye nikan, pẹlu I2 ifoju ni 65% fun gbogbo awọn ọdọ. Awọn iye fun I2 of 50% and 75% are considered to represent moderate and high heterogeneity respectively [36]. Nigbati a ba ṣe atupale nipasẹ ibalopọ, awọn ipele pupọ ti ilopọ ni a rii: I2 = 86.4% for males and I2 = 95.8% for females. Subgroup analyses were conducted, but could not explain the heterogeneity. Kosenko et al. [29] tun royin itupale fun orisirisi orisi ti ibalopo aṣayan iṣẹ-ṣiṣe ati sexting ninu eyi ti heterogeneity ti a iṣiro lati wa ni I2 = 98.5% (gbogbo iṣẹ-ṣiṣe ibalopo); I2 = 87.5% (unprotected sex) and I2 = 42.7% (number of sex partners). Given the high levels of heterogeneity found, findings should be treated with caution.

Ko ṣee ṣe lati ṣe ayẹwo iwọn ti agbekọja iwadi ni awọn atunyẹwo fun gbogbo awọn abajade ti o royin. Sibẹsibẹ, gẹgẹbi a ti ṣe yẹ, a rii pe fun diẹ ninu awọn abajade ifapọ pupọ wa ninu awọn ẹkọ ti o wa pẹlu awọn atunwo ati ni awọn itupalẹ-meta. Eyi pẹlu iṣipopada ninu awọn ijabọ awọn iwadii lori ajọṣepọ laarin lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati awọn igbagbọ ibalopọ, awọn ihuwasi ati iṣẹ ṣiṣe ati laarin iṣẹ ṣiṣe ibalopọ ati ikopa ninu sexting. Ifisi ti iwadii kanna tabi awọn iwadii ni awọn atunwo pupọ le funni ni idaniloju pe awọn atunwo kọọkan ti ṣe ni deede ati awọn abajade wọn ṣe afihan awọn iwe ti o wa. Bibẹẹkọ, wiwa awọn ijinlẹ akọkọ agbekọja ni awọn atunwo jẹ idanimọ lati jẹ ọran ti o pọju fun awọn RoRs [16, 18]. For example, study overlap can be a potential source of bias, when specific studies, particularly those that are small or of poorer quality, become over-represented through their inclusion in multiple reviews [16]. O tun le ja si apọju iwọn ati agbara ti ipilẹ ẹri.

Key eri ela ati ojo iwaju iwadi

Oro ti aworan iwokuwo ni wiwa ọpọlọpọ awọn ohun elo ti o yatọ ati iru akoonu ti a wo le jẹ pataki ni awọn ofin ti awọn ipalara ti o pọju, bi a ti ṣe afihan nipasẹ awọn awari lori ibatan laarin iwa-ipa ati aworan iwokuwo (ie ọna asopọ pẹlu ifinran ni a mọ nikan nigbati a wo aworan iwokuwo iwa-ipa. ). Lakoko ti diẹ ninu awọn iwadii ti dojukọ awọn orisun kan pato ti ohun elo, gẹgẹbi awọn aworan iwokuwo ori ayelujara, awọn iwadii pẹlu awọn ọdọ dabi ẹni pe wọn ti tọju aworan iwokuwo pupọ bi nkan isokan ni awọn ofin ti akoonu. Gẹgẹbi diẹ ninu awọn onkọwe ti ṣe idanimọ, iwulo wa fun iwadii diẹ sii ti o ṣe iwadii lọtọ, tabi ṣe iyatọ awọn ipa ti, awọn oriṣi akoonu onihoho.23].

Lakoko ti o wa ni ibakcdun pe ọpọlọpọ awọn ọdọ n wọle si aṣa aṣa ga, abuku tabi awọn aworan iwokuwo iwa-ipa, aini gbogbogbo tun wa ti imọ ati oye nipa kini ohun elo onihoho ti awọn ọdọ n wo nitootọ [21, 22]. Current discourse is based largely on opinion or speculation about what young people are accessing [21]. Iwadi diẹ sii ni a nilo lati ṣe iwadii iru akoonu onihoho ti awọn ọdọ n wo kuku ju gbigbekele arosọ.

Evidence was identified to suggest that young people are not uncritically accepting of what they see in pornographic material. For example, Peter and Valkenburg [22] fihan pe ni apapọ awọn ọdọ ko wo aworan iwokuwo bi orisun gidi ti alaye ibalopo. Bakanna, Horvath et al. [21] fihan ẹri pe ọpọlọpọ awọn ọdọ mọ pe awọn aworan iwokuwo le ṣe afihan awọn ifiranṣẹ ti o daru nipa iṣẹ-ibalopo, awọn ibatan, agbara ati awọn apẹrẹ ti ara. Iru awari wa ni ibamu pẹlu awọn iwadii media miiran, eyiti o tọka si pe awọn ọdọ kii ṣe awọn 'dupes' palolo lasan tabi 'olufaragba' ti awọn ifiranṣẹ media. Dipo, awọn ọdọ ni a rii lati gba ipa pataki ati ipa ni itumọ awọn oriṣiriṣi awọn media [37,38,39,40].

Various authors including Attwood [34] ati Horvath et al. [21] ti ṣe afihan iye ti ṣiṣe iwadi diẹ sii ti o ni idojukọ lori awọn ọna ti awọn ọdọ ti n wo gangan, loye ati ṣe alabapin pẹlu awọn ọna oriṣiriṣi ti awọn media ti o han gbangba. Iwadi ti o ni agbara siwaju sii ti o ṣawari awọn nkan ti o ni ipa lori awọn iwoye awọn ọdọ ti awọn aworan iwokuwo, ati awọn aati wọn si rẹ, le jẹ alaye ni pataki.

Ifiranṣẹ ti kii ṣe ifọkanbalẹ ti sexts ni a damọ bi ibakcdun pataki kan. Awọn abajade odi ti o pọju fun olufiranṣẹ ni a royin ti o ba jẹ pe awọn sexts jẹ gbangba, eyiti o pẹlu ibajẹ olokiki, ikọlu ati ipanilaya ayelujara. Sibẹsibẹ, o ṣe pataki lati mọ pe iru awọn abajade bẹẹ kii ṣe abajade taara tabi eyiti ko ṣee ṣe ti fifiranṣẹ sext kan. Dipo wọn jẹ abajade lati jijẹ igbẹkẹle ati lati ibawi olufaragba ati awọn aṣa aṣa akọ tabi abo ti o ni ibatan si kini ihuwasi ibalopọ itẹwọgba ati aṣoju ara ẹni, ni pataki fun awọn ọmọbirin.14, 41]. Awọn ijinlẹ ti o ni imọran daba pe pinpin aisi-igbagbọ ti sexts nigbagbogbo kan awọn ọmọbirin, ṣugbọn eyi ko ṣe atilẹyin nipasẹ data pipo ti o wa tẹlẹ. Ayẹwo-meta ti o ṣe nipasẹ Madigan et al. [42] ko ri ajọṣepọ laarin ibalopo / abo ati itankalẹ ti boya nini sext siwaju laisi aṣẹ tabi ṣiṣe sexting ti kii ṣe itẹwọgba. Awọn onkọwe ṣe ikilọ pe awọn itupalẹ-meta lori pinpin ti kii ṣe ifọkanbalẹ ti sexts da lori awọn iwọn ayẹwo kekere ati ṣeduro iwadii afikun lati ṣe ayẹwo itankalẹ. Ni afikun si awọn ijinlẹ pipo siwaju, ifiranšẹ aiṣe-afẹfẹ ti sexts nipasẹ awọn ọdọ ṣe atilẹyin fun idanwo kan pato ati diẹ sii ni ijinle nipa lilo awọn ọna didara. Iwadi ti a pinnu lati sọfun awọn ọgbọn lati ṣe idiwọ pinpin aiṣedeede ti sexts le ṣe pataki ni pataki.

Multiple review authors identified a lack of research on the influence of social identities such as ethnicity, sexual orientation or disability on outcomes. This is a potentially important gap in knowledge, especially as the reported prevalence data suggest that involvement with sexting and/or pornography may be higher in LGBT individuals and those from ethnic minority groups [22, 25, 28, 43]. Notably, some studies have indicated that LBGT young people use pornography as a key source of information about sex, as well as to explore their sexual identity and to determine their readiness to engage in sexual activity [21, 22, 33, 44]. Research that adopts an intersectionality perspective would be beneficial for understanding the combined influence of social identities on outcomes of interest.

Ipilẹ ẹri lọwọlọwọ ko ni iyatọ agbegbe, pẹlu pupọ julọ awọn awari ti o wa lati awọn iwadii ti a ṣe ni nọmba kekere ti awọn orilẹ-ede nikan. Iwọn ti eyiti awọn awari jẹ gbogbogbo jakejado awọn orilẹ-ede ko ṣe akiyesi. Atunyẹwo kan ṣe idanimọ iwọn si eyiti orilẹ-ede kan ni aṣa ominira bi ipin kan ti npinnu aye, tabi iwọn, ti awọn iyatọ abo ni lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo [22]. Asa ati awọn ifosiwewe pato ti orilẹ-ede miiran tun ṣee ṣe lati ni agba ibatan laarin lilo aworan iwokuwo ati sexting ati awọn igbagbọ ẹni kọọkan, awọn ihuwasi, ihuwasi ati alafia. Fun apẹẹrẹ, iraye si okeerẹ, ibaramu ati ibalopọ didara ati ẹkọ ibatan.

Whilst some positive aspects to pornography and engaging in sexting were identified, the predominant focus of the studies reported across reviews, was on potential negative outcomes, or outcomes that were framed by review authors as negative. The need for more quantitative studies to adopt a wider perspective and examine the potential positives associated with pornography use for young people was highlighted in reviews by Peter and Valkenburg [22] and Koletić [23].

idiwọn

We conducted this RoR using methods that were consistent with the key principles outlined in published guidance, for example Pollock et al. 2016 [45] and 2020 [46]. RoR yii ni opin nipasẹ idojukọ pato ti a gba ni awọn atunyẹwo kọọkan, ati didara ijabọ lori awọn ẹkọ akọkọ ati awọn awari wọn nipasẹ awọn onkọwe atunyẹwo. Diẹ ninu awọn awari le jẹ ti yọkuro, ti a yan ni ijabọ tabi royin ni aipe. Mejeeji lilo awọn aworan iwokuwo ati sexting jẹ awọn ọran ti o ni itara ati nitoribẹẹ ijabọ awọn ihuwasi le ti ni ipa nipasẹ aiṣedeede ifẹ awujọ. Fere gbogbo awọn atunwo nikan ni awọn iwadi ti a gbejade ni awọn iwe iroyin atunyẹwo ẹlẹgbẹ ati ti a kọ ni Gẹẹsi, eyiti o tun le jẹ orisun ojuṣaaju.

The age group of interest for this RoR was children and young people up to early adulthood, but multiple reviews included studies that had an upper age limit over nineteen years old. In addition, the reviews by both Kosenko et al. [29] ati Watchirs Smith et al. [31] included at least three studies with individuals aged 18 years and older only. The wide age range of the included studies in some reviews, and the fact that data in a number of studies were derived from individuals aged 18 years and over only, are therefore potential limitations in the context of examining the experiences of children and younger adults.

A ṣe idanimọ awọn atunwo ti a tẹjade titi di kutukutu Igba Irẹdanu Ewe 2018, ṣugbọn awọn abajade ti ko ṣee ṣe da lori data ti a gba lati awọn ikẹkọ akọkọ iṣaaju. Awọn onkọwe atunyẹwo ko wa kọja 2017 fun awọn ẹkọ akọkọ lori sexting ati 2015 fun awọn ti o wa lori aworan iwokuwo. Nitorinaa, data ti a tẹjade ni ọdun mẹta si marun sẹhin ko ni aṣoju ninu RoR yii. Awọn atunyẹwo tun le ti wa ni atẹjade lati ọdun 2018 lori lilo iwokuwo ati ibalopọ laarin awọn ọdọ. Sibẹsibẹ, ko ṣeeṣe pupọ pe eyikeyi awọn atunwo ti o yẹ ti a tẹjade ni akoko kukuru yẹn yoo ti yipada ni pataki awọn awari wa ati igbelewọn ti ipilẹ ẹri.

We used modified DARE criteria to critically appraise included reviews and this is acknowledged as a potential limitation. The DARE criteria were not originally designed as a tool for quality assessment and have not been validated for the task. Whilst the criteria focus on a relatively small number of characteristics, reviewers were able to supplement the criteria when conducting the appraisal by recording any key observations regarding potential methodological issues or sources of bias. We incorporated these observations into the findings of the appraisal process.

ipinnu

Ẹri jẹ idanimọ ti o so pọ lilo aworan iwokuwo mejeeji ati ibalopọ laarin awọn ọdọ si awọn igbagbọ kan pato, awọn ihuwasi ati awọn ihuwasi. Sibẹsibẹ, ẹri naa nigbagbogbo jẹ aisedede ati pupọ ninu rẹ ti o wa lati awọn iwadi-apakan, eyiti o ṣe idiwọ idasile ibatan idi kan. Ipilẹ ẹri ti o wa lọwọlọwọ tun ni opin nipasẹ awọn ọran ilana ilana miiran ti o wa ninu awọn ẹkọ akọkọ ati si awọn atunyẹwo ti awọn ẹkọ wọnyi, ati nipasẹ awọn ela bọtini ninu awọn iwe-iwe, eyiti o jẹ ki awọn ipinnu iyaworan nira.

Ni ojo iwaju, lilo awọn imọ-ẹrọ ti o ni imọra diẹ sii ati lile le ṣe iranlọwọ lati ṣe alaye awọn ibatan ti iwulo. Bí ó ti wù kí ó rí, ó ṣe pàtàkì láti mọ̀ pé irú ìwádìí bẹ́ẹ̀ kò ṣeé ṣe kí ó lè pinnu tàbí ya ara rẹ̀ sọ́tọ̀ pẹ̀lú ìdánilójú nípa ipa’ àwọn àwòrán oníhòòhò àti ìṣekúṣe lórí àwọn ọ̀dọ́. Awọn ijinlẹ didara ti o funni ni iwuwo si awọn ohun ti awọn ọdọ funrara wọn ni ipa pataki lati ṣe ni nini oye ti o ni kikun ati oye ti ibatan wọn pẹlu awọn aworan iwokuwo ati sexting.

Wiwa ti data ati awọn ohun elo

Ko ṣiṣẹ fun.

awọn akọsilẹ

- 1.

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/searchstrategies.asp A slightly amended version of the search filter was used for this RoR.

- 2.

Awọn awari lati inu atunyẹwo nipasẹ Handschuh et al. ti o wa ninu ijabọ si DHSC da lori alapejọ alapejọ ti a tẹjade ni ọdun 2018. Awọn abajade ti a royin ninu iwe lọwọlọwọ da lori nkan akọọlẹ kikun ti awọn onkọwe ṣe atẹjade lori atunyẹwo wọn ni ọdun 2019.

kuru

- IC:

- Aago igbagbọ

- DHSC:

- Sakaani ti Ilera ati Itọju Awujọ

- LGBT:

- Ọkọnrin, onibaje, Ălàgbedemeji, transgender

- TABI:

- Iwọn idiwọn

- RoR:

- Atunwo ti agbeyewo