THE REALLY SHORT VERSION: Some years ago, David Ley and study spokesperson Nicole Prause teamed up to write a Psychology Today blog post about Steele et al., 2013 called “Your Brain on Porn – It’s NOT Addictive“. The blog post appeared 5 months before Prause’s EEG study was formally published. Its oh-so-catchy title is misleading as it has nothing to do with Your Brain on Porn or the neuroscience presented there. Instead, David Ley’s March, 2013 blog post limits itself to a single flawed EEG study – Steele et al., 2013.

Update: In this 2018 presentation Gary Wilson exposes the truth behind 5 questionable and misleading studies, including this study (Steele et al., 2013): Porn Research: Fact or Fiction?

David Ley is the author of The Myth of Sex Addiction, and he religiously denies both sex and porn addiction. Ley has written 30 or so blog posts attacking porn-recovery forums, and dismissing porn addiction and porn-induced ED. Ley & Prause not only teamed up to write Ley’s Psychology Today blog post about Steele et al., 2013, they later joined forces to publish a 2014 paper dismissing porn addiction.

We often see Ley’s Psychology Today blog post referenced in debates about porn addiction. While many cite it as their primary evidence debunking the existence of porn addiction, few have any idea what Steele et al., 2013 actually reported. If indiscriminate Google searches is all you have, this is what you post. In reality, Prause’s 2013 EEG study actually supports the porn addiction model and did not find what the Ley or Prause claims that it did. Seven peer-reviewed analyses of Steele et al. 2013 describe how the Steele et al. findings lend support to the porn addiction model. The papers are in accord with the YBOP critique in that we all agree that Steele et al. actually found the following:

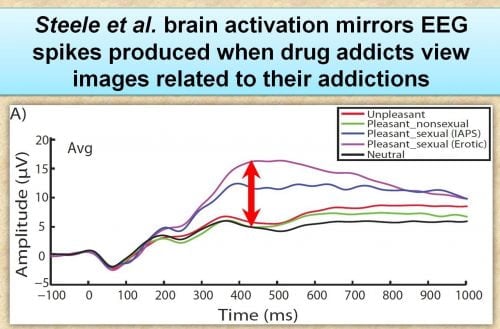

- Frequent porn users had greater cue-reactivity (higher EEG readings) to sexual images relative to neutral pictures (same as drug addicts do when exposed to cues related their addiction).

- Individuals with greater cue-reactivity to porn had less desire for sex with a partner (but not lower desire to masturbate to porn). This is a sign of both sensitization and desensitization.

Three of the papers also describe the study’s flawed methodology and unsubstantiated conclusions. Paper #1 is solely devoted to Steele et al., 2013. Papers 2-8 contain sections analyzing Steele et  al., 2013:

al., 2013:

- ‘High Desire’, or ‘Merely’ An Addiction? A Response to Steele et al. (2013), by Donald L. Hilton, Jr., MD

- Neural Correlates of Sexual Cue Reactivity in Individuals with and without Compulsive Sexual Behaviours (2014), by Valerie Voon, Thomas B. Mole, Paula Banca, Laura Porter, Laurel Morris, Simon Mitchell, Tatyana R. Lapa, Judy Karr, Neil A. Harrison, Marc N. Potenza, and Michael Irvine

- Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update (2015), by Todd Love, Christian Laier, Matthias Brand, Linda Hatch & Raju Hajela

- Is Internet Pornography Causing Sexual Dysfunctions? A Review with Clinical Reports (2016), by Brian Y. Park, Gary Wilson , Jonathan Berger, Matthew Christman, Bryn Reina, Frank Bishop, Warren P. Klam and Andrew P. Doan

- Conscious and Non-Conscious Measures of Emotion: Do They Vary with Frequency of Pornography Use? (2017) by Sajeev Kunaharan, Sean Halpin, Thiagarajan Sitharthan, Shannon Bosshard, and Peter Walla

- Neurocognitive mechanisms in compulsive sexual behavior disorder (2018), Ewelina Kowalewska, Joshua B. Grubbs, Marc N. Potenza, Mateusz Gola, Małgorzata Draps, and Shane W.Kraus.

- Online Porn Addiction: What We Know and What We Don’t—A Systematic Review (2019), Rubén de Alarcón, Javier I. de la Iglesia, Nerea M. Casado and Angel L. Montejo.

- The Initiation and Development of Cybersex Addiction: Individual Vulnerability, Reinforcement Mechanism and Neural Mechanism” (2019) by He Wei, Shi Yahuan, Zhang wei, Luo Wenbo, He Wiezhan

Note: Over 25 studies falsify the claim that sex & porn addicts “just have high sexual desire”. This is important as Prause claimed that her subjects simply had higher libidos (but they didn’t, as you will see below).

Introduction

The SPAN Lab study: “Sexual Desire, not Hypersexuality, is Related to Neurophysiological Responses Elicited by Sexual Images” (known as Steele et al., 2013).

This 2013 EEG study was touted in the media as evidence against the existence of porn addiction (or alternately, sex addiction). In reality, YBOP lists this study as supporting the existence of porn addiction. Why? The study reported higher EEG readings (P300) when subjects were exposed to porn photos. A higher P300 occurs when addicts are exposed to cues (such as images) related to their addiction.

In addition, the study reported that individuals with greater cue-reactivity to porn had less desire for sex with a partner (but not lower desire to masturbate to porn). To put another way – individuals with more brain activation and cravings for porn would rather masturbate to porn than have sex with a real person.

In the press, study spokesman Nicole Prause claimed that porn users merely had high libido, yet the results of the study say something quite different. In fact, greater cue-reactivity to porn, coupled with lower desire for sex with real partners, aligns the 2014 Cambridge University brain scan study on porn addicts. As you will see below, the actual findings of this EEG study in no way match the concocted headlines or the author’s claims.

In the following critique we dismantle the unfounded claims and reveal what the study actually found, and why it should never have been published. I suggest the short version, which addresses the three main claims promulgated in the media.

Update: Much has transpired since July, 2013. UCLA did not renew Nicole Prause’s contract (early 2015). No longer an academic Prause has engaged in multiple documented incidents harassment and defamation as part of an ongoing “astroturf” campaign to persuade people that anyone who disagrees with her conclusions deserves to be reviled. Prause has accumulated a long history of harassing authors, researchers, therapists, reporters and others who dare to report evidence of harms from internet porn use. She appears to be quite cozy with the pornography industry, as can be seen from this image of her (far right) on the red carpet of the X-Rated Critics Organization (XRCO) awards ceremony. (According to Wikipedia the XRCO Awards are given by the American X-Rated Critics Organization annually to people working in adult entertainment and it is the only adult industry awards show reserved exclusively for industry members.[1]). It also appears that Prause may have obtained porn performers as subjects through another porn industry interest group, the Free Speech Coalition. The FSC-obtained subjects were allegedly used in her hired-gun study on the heavily tainted and very commercial “Orgasmic Meditation” scheme (now being investigated by the FBI). Prause has also made unsupported claims about the results of her studies and her study’s methodologies. For much more documentation, see: Is Nicole Prause Influenced by the Porn Industry?

Update (Summer, 2019): On May 8, 2019 Donald Hilton, MD filed a defamation per se lawsuit against Nicole Prause & Liberos LLC (Dr. Hilton critiqued Steele et al. in 2014). On July 24, 2019 Donald Hilton amended his defamation complaint to highlight (1) a malicious Texas Board of Medical Examiners complaint, (2) false accusations that Dr. Hilton had falsified his credentials, and (3) affidavits from 9 other Prause victims of similar harassment (John Adler, MD, Gary Wilson, Alexander Rhodes, Staci Sprout, LICSW, Linda Hatch, PhD, Bradley Green, PhD, Stefanie Carnes, PhD, Geoff Goodman, PhD, Laila Haddad.)

THE SHORT VERSION

Participants: 52 test subjects were recruited through ads “requesting people who were experiencing problems regulating their viewing of sexual images.” The participants (average age 24) were a mix of males (39) and females (13). 7 participants were non-heterosexual. A major flaw in the Prause Studies (Steele et al., 2013, Prause et al., 2013, Prause et al., 2015) is that no one knows which, if any, of Prause’s subjects were actually porn addicts. In a 2013 interview Nicole Prause admits that a number of her subjects experienced only minor problems (which means they were not porn addicts):

“This study only included people who reported problems, ranging from relatively minor to overwhelming problems, controlling their viewing of visual sexual stimuli.”

Besides not establishing which of the subjects were porn addicted, all the Prause studies, including this one, did not screen subjects for mental disorders, compulsive behaviors, or other addictions. This is critically important for any “brain study” on addiction, lest confounds render results meaningless

Another fatal flaw is that Steele et al. subjects were not heterogeneous (same goes for other Prause studies). They were men and women, including 7 non-heterosexuals, but were all shown standard, possibly uninteresting, male+female porn. This alone discounts any findings. Why? Study after study confirms that men and women have significantly different brain responses to sexual images or films. This is why serious addiction researchers match subjects carefully. Since the Prause Studies did not, the results are unreliable, and cannot be used to falsify anything.

What They Did: EEG readings (electrical activity on the scalp) were taken as participants viewed 225 pictures. 38 of the pictures were sexual, and all involved one woman and one man. This particular EEG reading (P300) measures attentiveness to stimuli. Participants also completed 4 questionnaires: Sexual Desire Inventory (SDI), Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS), Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Questionnaire (SBOSBQ), and the Pornography ConsumptionEffect Scale (PCES).

The questionnaire employed to assess “porn addiction” (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) was not validated as a screening instrument for porn addiction. It was created in 1995 and designed with uncontrolled sexual relations (with partners) in mind, in connection with investigating the AIDS epidemic. The SCS says:

“The scale has been should [shown?] to predict rates of sexual behaviors, numbers of sexual partners, practice of a variety of sexual behaviors, and histories of sexually transmitted diseases.”

Moreover, they administered the questionnaire to the female subjects. Yet the SCS’s developer warns that this tool won’t show psychopathology in women,

“Associations between sexual compulsivity scores and other markers of psychopathology showed different patterns for men and women; sexual compulsivity was associated with indexes of psychopathology in men but not in women.”

Put simply, the 3 Prause Studies (Steele et al., 2013, Prause et al., 2013, Prause et al., 2015) all involved the same subjects – and all failed to assess whether the subjects were porn addicts or not. Prause admitted that many of the subjects had little difficulty controlling use. All of the subjects would have to have been confirmed porn addicts to permit a legitimate comparison with a group of non-porn addicts.

Purpose: To seek a correlation between EEG reading averages and participants’ scores on the various questionnaires—on the theory that any correlation would shed light on whether problematic porn use is a function of addiction or mere high libido.

Outcome: The authors of the study claim to have found a single statistically significant correlation among all the data gathered:

“Larger P300 amplitude differences to pleasant sexual stimuli, relative to neutral stimuli, was negatively related to measures of sexual desire, but not related to measures of hypersexuality.”

Translation: Negatively means lower desire. Individuals with greater cue-reactivity to porn had lower desire to have sex with a partner (but not lower desire to masturbate). To put another way – individuals with more brain activation and cravings for porn would rather masturbate to porn than have sex with a real person. This finding is followed by this conclusion:

Conclusion: Implications for understanding hypersexuality as high desire, rather than disordered, are discussed.

Huh? How did negatively (lower) get turned into positively (higher)? Why did greater cue-reactivity to porn correlating with lower desire to have sex with a partner lead to a conclusion saying hypersexuality is to be understood as high desire? No one knows, but this bizarre turnaround was the basis for many of the headlines. Nicole Prause functioned as the spokesman for Steele et al., 2013 In the media Prause presents the following arguments to support her claim that “porn addiction does not exist”:

- In TV interviews and in the UCLA press release researcher Nicole Prause claims that subjects’ brains did not respond like other addicts.

- The headlines and the study’s conclusion suggest that “hypersexuality” is understood as “high desire“, yet the study reports that subjects with greater brain activation to porn have less desire for sex.

- Steele et al. argues that the lack of correlations between EEG readings and certain questionnaires means porn addiction doesn’t exist.

You can read the whole analysis, but here’s the scoop on 1, 2 and 3 above.

CLAIM NUMBER 1: Subjects’ brain response differs from other types of addicts (cocaine was the example).

Much of the hype and headlines surrounding this study rest upon this unsupported claim. Here’s the hype:

“If they indeed suffer from hypersexuality, or sexual addiction, their brain response to visual sexual stimuli could be expected be higher, in much the same way that the brains of cocaine addicts have been shown to react to images of the drug in other studies.”

Reporter: “They were shown various erotic images, and their brain activity monitored.”Prause: “If you think sexual problems are an addiction, we would have expected to see an enhanced response, maybe, to those sexual images. If you think it’s a problem of impulsivity, we would have expected to see decreased responses to those sexual images. And the fact that we didn’t see any of those relationships suggests that there’s not great support for looking at these problem sexual behaviors as an addiction.”

What was the purpose of the study?

Prause: Our study tested whether people who report such problems look like other addicts from their brain responses to sexual images. Studies of drug addictions, such as cocaine, have shown a consistent pattern of brain response to images of the drug of abuse, so we predicted that we should see the same pattern in people who report problems with sex if it was, in fact, an addiction.

Does this prove sex addiction is a myth?

Prause: If our study is replicated, these findings would represent a major challenge to existing theories of sex “addiction”. The reason these findings present a challenge is that it shows their brains did not respond to the images like other addicts to their drug of addiction.

The above claims that subjects “brains did not respond like other addicts” is without support. This assertion is nowhere to be found in the actual study. It’s only found in Prause’s interviews. In this study subjects had higher EEG (P300) readings when viewing sexual images – which is exactly what occurs when addicts view images related to their addiction (as in this study on cocaine addicts). Commenting under the Psychology Today interview of Prause, senior psychology professor emeritus John A. Johnson said:

“My mind still boggles at the Prause claim that her subjects’ brains did not respond to sexual images like drug addicts’ brains respond to their drug, given that she reports higher P300 readings for the sexual images. Just like addicts who show P300 spikes when presented with their drug of choice. How could she draw a conclusion that is the opposite of the actual results? I think it could be due to her preconceptions–what she expected to find.”

Mustanski asks, “What was the purpose of the study?” And Prause replies, “Our study tested whether people who report such problems [problems with regulating their viewing of online erotica] look like other addicts from their brain responses to sexual images.”

But the study did not compare brain recordings from persons having problems regulating their viewing of online erotica to brain recordings from drug addicts and brain recordings from a non-addict control group, which would have been the obvious way to see if brain responses from the troubled group look more like the brain responses of addicts or non-addicts.

Instead, Prause claims that their within-subject design was a better method, where research subjects serve as their own control group. With this design, they found that the EEG response of their subjects (as a group) to erotic pictures was stronger than their EEG responses to other kinds of pictures. This is shown in the inline waveform graph (although for some reason the graph differs considerably from the actual graph in the published article).

So this group who reports having trouble regulating their viewing of online erotica has a stronger EEG response to erotic pictures than other kinds of pictures. Do addicts show a similarly strong EEG response when presented with their drug of choice? We don’t know. Do normal, non-addicts show a response as strong as the troubled group to erotica? Again, we do not know. We don’t know whether this EEG pattern is more similar to the brain patterns of addicts or non-addicts.

The Prause research team claims to be able to demonstrate whether the elevated EEG response of their subjects to erotica is an addictive brain response or just a high-libido brain response by correlating a set of questionnaire scores with individual differences in EEG response. But explaining differences in EEG response is a different question from exploring whether the overall group’s response looks addictive or not.

A page with a debate between Nicole Prause (as anonymous) and John A. Johnson: John A. Johnson on Steele et al., 2013 (and Johnson debating Nicole Prause in comments section under his article about Steele et al.).

Simple: The claims that the subjects’ brains differed from other types of addicts is without support. In fact, the 2014 Cambridge University study (Voon et al., 2014) analyzed Steele et al. and agreed with Johnson: Steele et al. reported higher P300 in response to sexual images relative to neutral pictures (citation 25). From the Cambridge study:

“Our findings suggest dACC activity reflects the role of sexual desire, which may have similarities to a study on the P300 in CSB subjects correlating with desire [25] ……Studies of the P300, an event related potential used to study attentional bias in substance use disorders, show elevated measures with respect to use of nicotine [54], alcohol [55], and opiates [56], with measures often correlating with craving indices.”…..Thus, both dACC activity in the present CSB study and P300 activity reported in a previous CSB study may reflect similar underlying processes.”

This 2015 review the neuroscience literature summarized Steele et al.:

“So while these authors [303] claimed that their study refuted the application of the addiction model to CSB, Voon et al. posited that these authors actually provided evidence supporting said model.”

CLAIM NUMBER 2: The headlines & study’s conclusion suggest that “hypersexuality” is understood as “high desire“, yet the study reports that subjects with greater brain activation to porn have less desire for sex.

What you didn’t read in interviews and articles is that the study reported a negative correlation between “partnered sexual desire questions” and P300 readings. In other words, greater brain activation correlated with less desire for sex (but not less desire to masturbate to porn). Note Prause’s wording in this interview:

What is the main finding in your study?

“We found that the brain’s response to sexual pictures was not predicted by any of three different questionnaire measures of hypersexuality. Brain response was only predicted by a measure of sexual desire. In other words, hypersexuality does not appear to explain brain differences in sexual response any more than just having a high libido.”

Note that Prause said by “a measure” of sexual desire, not by “the enitre Sexual Desire Inventory”. When all 14 questions were calculated there was no correlation, and no headline. Even more confusing is the study title which used “sexual desire”, rather than what was actually found: “negative correlation with selected questions about partnered sex from the SDI“, but no correlation when all SDI questions were calculated“.

Here’s John A. Johnson PhD commenting under the Prause interview:

“The Prause group reported that the only statistically significant correlation with the EEG response was a negative correlation (r=-.33) with desire for sex with a partner. In other words, there was a slight tendency for subjects with strong EEG responses to erotica to have lower desire for sex with a partner. How does that say anything about whether the brain responses of people who have trouble regulating their viewing of erotica are similar to addicts or non-addicts with a high libido?”

A month later John A. Johnson PhD published a Psychology Today blog post about Prause’s EEG study and what he perceived as biases on both sides of the issue. Nicole Prause (as anonymous) commented underneath taking Johnson to task for linking to this YBOP critique. Johnson replied with the following comment for which Prause had no response:

If the point of the study was to show that “all people” (not just alleged sex addicts) show a spike in P300 amplitude when viewing sexual images, you are correct–I do not get the point, because the study employed only alleged sex addicts. If the study *had* employed a non-addict comparison group and found that they also showed the P300 spike, then the researchers would have had a case for their claim that the brains of so-called sex addicts react that same as non-addicts, so maybe there is no difference between alleged addicts and non-addicts. Instead, the study showed that the self-described addicts showed the P300 spike in response to their self-described addictive “substance” (sexual images), just like cocaine addicts show a P300 spike when presented with cocaine, alcoholics show a P300 spike when presented with alcohol, etc.

As for what the correlations between P300 amplitude and other scores show, the only significant correlation was a *negative* correlation with desire for sex with a partner. In other words, the stronger the brain response to the sexual image, the *less* desire the person had for sex with a real person. This sounds to me like the profile of someone who is so fixated on images that s/he has trouble connecting sexually with people in real life. I would say that this person has a problem. Whether we want to call this problem an “addiction” is still arguable. But I do not see how this finding demonstrates the *lack* of addiction in this sample.

Simple: No correlation existed between EEG readings and the 14-question sexual desire inventory. Goodbye study title and headlines. Even if a positive correlation existed, the claim that “high desire” is mutually exclusive from “addiction” is preposterous. More to the point, P300 readings were negatively correlated (r=-.33) with desire for sex with a partner. Put simply – subjects who had greater cue-reactivity to porn had less desire for sex with a real person.

CLAIM NUMBER 3: Porn addiction doesn’t exist because of a lack of correlation between subjects’ EEG readings and subjects’ scores on the Sexual Compulsivity Scale.

The lack of correlations between EEG and questionnaires is easily explained by many factors:

1) The subjects were men and women, including 7 non-heterosexuals, but were all shown standard, possibly uninteresting, male+female images. This alone discounts any findings. Why?

- Study after study confirm that men and women have significantly different brain responses to sexual images or films.

- Valid addiction brain studies involve homogenous subjects: same sex, same sexual orientation, along with similar ages and IQ’s.

- How can researchers justify non-heterosexuals in an experiment with only heterosexual porn – and then draw vast conclusions from a (predictable) lack of correlation?

2) The subjects were not pre-screened. Valid addiction brain studies screen individuals for pre-existing conditions (depression, OCD, other addictions, etc.). See the Cambridge study for an example of proper screening & methodology.

3) Subjects experienced varying degrees of compulsive porn use, from severe to relatively minor. A quote from Prause:

“This study only included people who reported problems, ranging from relatively minor to overwhelming problems, controlling their viewing of visual sexual stimuli.”

This alone could explain varying results that didn’t correlate in a predictable way. Valid addiction brain studies compare a group of addicts to non-addicts. This study had neither.

4) The SCS (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) isn’t a valid assessment test for Internet-porn addiction or for women. It was created in 1995 and designed with uncontrolled sexual relations in mind (in connection with investigating the AIDS epidemic). The SCS says:

“The scale has been should [shown?] to predict rates of sexual behaviors, numbers of sexual partners, practice of a variety of sexual behaviors, and histories of sexually transmitted diseases.”

Moreover, the SCS’s developer warns that this tool won’t show psychopathology in women,

“Associations between sexual compulsivity scores and other markers of psychopathology showed different patterns for men and women; sexual compulsivity was associated with indexes of psychopathology in men but not in women.”

Like the SCS, the second questionnaire (the CBSOB) has no questions about Internet porn use. It was designed to screen for “hypersexual” subjects, and out of control sexual behaviors.

Simple: A valid addiction “brain study” must: 1) have homogenous subjects and controls, 2) screen for other mental disorders and addictions, 3) use validated questionnaires and interviews to assure the subjects are actually addicts. This EEG study on porn users did none of these. This alone discounts the study’s results.

Analysis of Steele et al. from this peer-reviewed review of the literature – Neuroscience of Internet Pornography Addiction: A Review and Update (2015)

An EEG study on those complaining of problems regulating their viewing of internet pornography has reported the neural reactivity to sexual stimuli [303]. The study was designed to examine the relationship between ERP amplitudes when viewing emotional and sexual images and questionnaire measures of hypersexuality and sexual desire. The authors concluded that the absence of correlations between scores on hypersexuality questionnaires and mean P300 amplitudes when viewing sexual images “fail to provide support for models of pathological hypersexuality” [303] (p. 10). However, the lack of correlations may be better explained by arguable flaws in the methodology. For example, this study used a heterogeneous subject pool (males and females, including 7 non-heterosexuals). Cue-reactivity studies comparing the brain response of addicts to healthy controls require homogenous subjects (same sex, similar ages) to have valid results. Specific to porn addiction studies, it’s well established that males and females differ appreciably in brain and autonomic responses to the identical visual sexual stimuli [304,305,306]. Additionally, two of the screening questionnaires have not been validated for addicted IP users, and the subjects were not screened for other manifestations of addiction or mood disorders.

Moreover, the conclusion listed in the abstract, “Implications for understanding hypersexuality as high desire, rather than disordered, are discussed” [303] (p. 1) seems out of place considering the study’s finding that P300 amplitude was negatively correlated with desire for sex with a partner. As explained in Hilton (2014), this finding “directly contradicts the interpretation of P300 as high desire” [307]. The Hilton analysis further suggests that the absence of a control group and the inability of EEG technology to discriminate between “high sexual desire” and “sexual compulsion” render the Steele et al. findings uninterpretable [307].

Finally, a significant finding of the paper (higher P300 amplitude to sexual images, relative to neutral pictures) is given minimal attention in the discussion section. This is unexpected, as a common finding with substance and internet addicts is an increased P300 amplitude relative to neutral stimuli when exposed to visual cues associated with their addiction [308]. In fact, Voon, et al. [262] devoted a section of their discussion analyzing this prior study’s P300 findings. Voon et al. provided the explanation of importance of P300 not provided in the Steele paper, particularly in regards to established addiction models, concluding,

Thus, both dACC activity in the present CSB study and P300 activity reported in a previous CSB study[303] may reflect similar underlying processes of attentional capture. Similarly, both studies show a correlation between these measures with enhanced desire. Here we suggest that dACC activity correlates with desire, which may reflect an index of craving, but does not correlate with liking suggestive of on an incentive-salience model of addictions. [262] (p. 7)

So while these authors [303] claimed that their study refuted the application of the addiction model to CSB, Voon et al. posited that these authors actually provided evidence supporting said model.

THE LONG VERSION

The Results Say One thing, While the Study’s Conclusions and Authors Imply the Opposite

The study’s title, along with the many headlines, state that a correlation (relation) was found between “sexual desire” as measured by the Sexual Desire Inventory and EEG readings. According to everything we can find, the SDI is a 14-question test. Nine of its questions address partnered (“dyadic”) sexual desire and four address solo (“solitary”) sexual desire. Just for clarification, the study’s negative correlation was attained with only the partnered sex questions from the SDI. There was no significant correlation between P300 readings and all the questions on the SDI. The study’s results taken from the abstract:

RESULTS: “Larger P300 amplitude differences to pleasant sexual stimuli, relative to neutral stimuli, was negatively related to measures of sexual desire, but not related to measures of hypersexuality.”

Translation: Subjects with greater cue-reactivity to porn (higher EEG’s) scored lower in their desire for sex with a partner (but not their desire to masturbate). To put it another way, greater cue-reactivity correlated with less desire to have sex (yet still desiring to masturbate to porn). Yet the very next sentence turns lower desire for sex with a partner into high sexual desire:

CONCLUSION: Implications for understanding hypersexuality as high desire, rather than disordered, are discussed.

Is Steele et al now claiming that they really found high sexual desire correlating with higher P300 readings? Well, that didn’t happen, as John Johnson PhD explained in this peer-reviewed rebuttal:

‘The single statistically significant finding says nothing about addiction. Furthermore, this significant finding is a negative correlation between P300 and desire for sex with a partner (r=−0.33), indicating that P300 amplitude is related to lower sexual desire; this directly contradicts the interpretation of P300 as high desire. There are no comparisons to other addict groups. There are no comparisons to control groups. The conclusions drawn by the researchers are a quantum leap from the data, which say nothing about whether people who report trouble regulating their viewing of sexual images have or do not have brain responses similar to cocaine or any other kinds of addicts’

Why must John Johnson remind the authors and everyone else, that Steel et al. actually found “lower desire for sex with a partner”, rather than “high sexual desire”? Because most of Steele et al. and the media blitz imply that cue-reactivity to porn correlated with high sexual desire. The conclusion taken from the abstract:

Conclusion: Implications for understanding hypersexuality as high desire, rather than disordered, are discussed.

Say what? But study reported that subjects with greater cue-reactivity had lower desire for sex with a partner.

In addition, the phrase “sexual desire” is repeated 63 times in the study, and the study’s title (Sexual Desire, Not Hypersexuality….) implies that higher brain activation to cues was associated with higher sexual desire. Read the study’s full conclusion and you too might assume the authors found higher rather than lower sexual desire:

In conclusion, the first measures of neural reactivity to visual sexual and non-sexual stimuli in a sample reporting problems regulating their viewing of similar stimuli fail to provide support for models of pathological hypersexuality, as measured by questionnaires. Specifically, differences in the P300 window between sexual and neutral stimuli were predicted by sexual desire, but not by any (of three) measures of hypersexuality. If sexual desire most strongly predicts neural responses to sexual stimuli, management of sexual desire, without necessarily addressing some of the proposed concomitants of hypersexuality, might be an effective method for reducing distressing sexual feelings or behaviors.

Nowhere do we see lower sexual desire. Instead we are given – “predicted by sexual desire” and “management of sexual desire” and “reducing distressing sexual feelings or behaviors.” Not only did the study hypnotize readers into believing porn addiction was really just high libido, Prause reinforced this meme in in her interviews: (note the wording)

What is the main finding in your study?

“We found that the brain’s response to sexual pictures was not predicted by any of three different questionnaire measures of hypersexuality. Brain response was only predicted by a measure of sexual desire. In other words, hypersexuality does not appear to explain brain differences in sexual response any more than just having a high libido.“

Prause said by “a measure” of sexual desire, not by “the entire Sexual Desire Inventory”. When all 14 questions were calculated there was no correlation, and no headline to turn upside down. Prause makes the same claim in her UCLA press release:

“The brain’s response to sexual pictures was not predicted by any of the three questionnaire measures of hypersexuality,” she said. “Brain response was only related to the measure of sexual desire. In other words, hypersexuality does not appear to explain brain responses to sexual images any more than just having a high libido.“

In both interviews it is suggested that higher P300 readings were related to “higher libido”. Everyone in the media bought it. Considering the findings, Steele et al. should have been called – “negative correlation with questions about partnered sex, but no correlation when all SDI questions were calculated“.

Simple: Cue-reactivity (P300 readings) were negatively correlated (r=-.33) with desire for sex with a partner. Put simply: less desire for sex correlated greater cue-reactivity for porn. Overall, no correlation existed between EEG readings and the entire 14-question sexual desire inventory. Even if a positive correlation existed, the claim that “high desire” is mutually exclusive from “addiction” is preposterous.

Finally, it’s important to note that the study contains two errors in regard to the SDI. Quoting the study:

“The SDI measures levels of sexual desire using two scales composed of seven items each.“

In fact, the Sexual Desire Inventory contains nine partnered questions, four solitary questions, and one question that cannot be categorized (#14).

Second mistake: Table 2 says the Solitary test score range is “3-26,” and yet the female mean exceeds it. It’s 26.46–literally off the charts. What happened? The four solitary sex questions (10-13) add up to a possible score of “31”.

The lively media blitz, which accompanied publication of this study, bases its attention-grabbing headlines on partial SDI results. Yet the study write-up contains glaring errors about the SDI itself, which do not engender confidence in the researchers.

High Desire is Mutually Exclusive with Addiction?

Although Steele et al. actually reported less desire for partnered sex correlating to cue-reactivity, it’s important to address the unbelievable claim that “high sexual desire” is mutually exclusive to porn addiction. Its irrationality becomes clear if one considers hypotheticals based on other addictions. (For more see this critique of Steele et al. – High desire’, or ‘merely’ an addiction? A response to Steele et al., by Donald L. Hilton, Jr., MD*.)

For example, does such logic mean that being morbidly obese, unable to control eating, and being extremely unhappy about it, is simply a “high desire for food?” Extrapolating further, one must conclude that alcoholics simply have a high desire for alcohol, right? In short, all addicts have “high desire” for their addictive substances and activities (called “sensitization”), even when their enjoyment of such activities declines due to other addiction-related brain changes (desensitization).

Most addiction experts consider “continued use despite negative consequences” to be the prime marker of addiction. After all, someone could have porn-induced erectile dysfunction and be unable to venture beyond his computer in his mother’s basement. Yet, according to these researchers, as long as he indicates “high sexual desire,” he has no addiction. This paradigm ignores everything known about addiction, including symptoms and behaviors shared by all addicts, such as severe negative repercussions, inability to control use, cravings, etc.

Is this study part of a rash of studies based on the peculiar logic that any measure of “high desire,” however questionable, grants immunity from addiction? A Canadian sexologist endeavored to paint this same picture in a 2010 paper entitled, Dysregulated sexuality and high sexual desire: distinct constructs? Noting that people who seek treatment for sexual behavior addictions report both dysregulated sexuality and high desire, he boldly concluded:

“The results of this study suggest that dysregulated sexuality, as currently conceptualized, labeled, and measured, may simply be a marker of high sexual desire and the distress associated with managing a high degree of sexual thoughts, feelings, and needs.”

Again, sexual behavior addiction itself produces cravings that often show up as “a high degree of sexual thoughts, feelings, and needs.” It’s simply wishful thinking to suggest “high sexual desire” eliminates the existence of addiction. Below are studies that directly refute “porn addiction is really high desre” model:

Quote: “Moreover, it was shown that problematic cybersex users report greater sexual arousal and craving reactions resulting from pornographic cue presentation. In both studies, the number and the quality with real-life sexual contacts were not associated to cybersex addiction.”

This fMRI study found that higher hours per week/more years of porn viewing correlated with less brain activation when exposed to photos of vanilla porn. Said the researchers:

“This is in line with the hypothesis that intense exposure to pornographic stimuli results in a downregulation of the natural neural response to sexual stimuli.”

Kühn & Gallinat also reported more porn use correlating with less reward circuit grey matter and disruption of the circuits involved with impulse control. In this article researcher Simone Kühn, said:

“That could mean that regular consumption of pornography more or less wears out your reward system.”

Kühn says existing psychological, scientific literature suggests consumers of porn will seek material with novel and more extreme sex games.

“That would fit perfectly the hypothesis that their reward systems need growing stimulation.”

Put simply, men who use more porn may need greater stimulation for the response level seen in lighter consumers, and photos of vanilla porn are unlikely to register as all that interesting. Less interest, equates to less attention, and lower EEG readings. End of story.

This study found that porn addicts had same brain activity as seen in drug addicts and alcoholics. The researchers also reported that 60% of subjects (average age: 25) had difficulty achieving erections/arousal with real partners, yet could achieve erections with porn. This finding completely dismantles the claim that compulsive porn users simply have higher sexual desire than those who aren’t compulsive porn users.

Why No Correlations Between Questionnaires And EEG Readings?

A major claim by Steele et al., 2013 is that the lack of correlations between subjects EEG readings (P300) and certain questionnaires means porn addiction doesn’t exist. Two major reasons account for the lack of correlation:

- The researchers chose vastly different subjects (women, men, heterosexuals, non-heterosexuals), but showed them all standard, possibly uninteresting, male+female sexual images. Put simply, the results of this study were dependent on the premise that males, females, and non-heterosexuals are no different in their response to sexual images. This is clearly not the case (below).

- The two questionaires Steele et al. relied upon in both EEG studies to assess “porn addiction” are not validated to screen for internet porn use/addiction. In the press, Prause repeatedly pointed to the lack of correlation between EEG scores and “hypersexuality” scales, but there is no reason to expect a correlation in porn addicts.

Unacceptable Diversity Of Test Subjects: The researchers chose vastly different subjects (women, men, heterosexuals, non-heterosexuals), but showed them all standard, possibly uninteresting, male+female porn. This matters, because it violates standard procedure for addiction studies, in which researchers select homogeneous subjects in terms of age, gender, orientation, even similar IQ’s (plus a homogeneous control group) in order to avoid distortions caused by such differences.

This is especially critical for studies like this one, which measured arousal to sexual images, as research confirms that men and women have significantly different brain responses to sexual images or films. This flaw alone explains the lack of correlations between EEG readings and questionnaires. Previous studies confirm significant differences between males and females in response to sexual images. See, for example:

- Sex differences in concordance rates between auditory event-related potentials and subjective sexual arousal.

- Gender Differences in Sexual Arousal and Affective Responses to Erotica.

- Sex in the Brain: The Relationship between Event Related Potentials and Subjective Sexual Arousal

- Sex differences in brain activation to emotional stimuli: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies

- Habituation of female sexual arousal to slides and film.

- Skin sympathetic nerve activity in humans during exposure to emotionally-charged images: sex differences

- The late positive potential (LPP) in response to varying types of emotional and cigarette stimuli in smokers: a content comparison

- Sex differences in interactions between nucleus accumbens and visual cortex by explicit visual erotic stimuli: an fMRI study.

- Affective picture perception: gender differences in visual cortex?

- Sex-specific content preferences for visual sexual stimuli.

- Sex differences in patterns of genital sexual arousal: measurement artifacts or true phenomena?

- Sex differences in viewing sexual stimuli: an eye-tracking study in men and women

- Men and women differ in amygdala response to visual sexual stimuli

- Effects of gender and relationship context in audio narratives on genital and subjective sexual response in heterosexual women and men.

- Sex differences in visual attention to erotic and non-erotic stimuli

- Sex Differences in Response to Visual Sexual Stimuli: A Review

- Skin conductance responses to visual sexual stimuli.

- Does subliminal exposure to sexual stimuli have the same effects on men and women? (2007)

- An fMRI Study of Responses to Sexual Stimuli as a Function of Gender and Sensation Seeking: A Preliminary Analysis (2016)

- The Late Positive Potential (LPP) in Response to Varying Types of Emotional and Cigarette Stimuli in Smokers: A Content Comparison (2016)

- The Effects of Positive Versus Negative Mood States on Attentional Processes During Exposure to Erotica (2016)

- The neural basis of sex differences in sexual behavior: A quantitative meta-analysis (2016)

- Neural correlates of gender differences in distractibility by sexual stimuli (2018)

- Fluctuations of estradiol during women’s menstrual cycle: Influences on reactivity towards erotic stimuli in the late positive potential (2018)

- Gender Differences in the Automatic Attention to Romantic Vs Sexually Explicit Stimuli (2018)

- Does dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) activation return to baseline when sexual stimuli cease? The role of DLPFC in visual sexual stimulation (2007)

- Connection between subjective sexual arousal and genital response: differences between men and women (2019)

- The Connection Between the Physiological and Psychological Reactions to Sexually Explicit Materials: A Literature Summary Using Meta-Analysis

Can we be confident that a non-heterosexual has the same enthusiasm for male-female porn as a heterosexual male? No, and his/her inclusion could distort EEG averages rendering meaningful correlations unlikely. See, for example, Neural circuits of disgust induced by sexual stimuli in homosexual and heterosexual men: an fMRI study.

Surprisingly, Prause herself stated in an earlier study (2012) that individuals vary tremendously in their response to sexual images:

“Film stimuli are vulnerable to individual differences in attention to different components of the stimuli (Rupp & Wallen, 2007), preference for specific content (Janssen, Goodrich, Petrocelli, & Bancroft, 2009) or clinical histories making portions of the stimuli aversive (Wouda et al.,1998).”

“Still, individuals will vary tremendously in the visual cues that signal sexual arousal to them (Graham, Sanders, Milhausen, & McBride, 2004).”

In a Prause study published a few weeks before this one she said:

“Many studies using the popular International Affective Picture System (Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1999) use different stimuli for the men and women in their sample.”

Maybe Prause should read her own statements to discover the reason why her current EEG readings varied so much. Individual differences are normal, and large variations are to be expected with a sexually diverse group of subjects.

Irrelevant Questionnaires: The SCS (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) cannot assess Internet-porn addiction. It was created in 1995 and designed with uncontrolled sexual relations in mind (in connection with investigating the AIDS epidemic). The SCS says:

“The scale has been should [shown?] to predict rates of sexual behaviors, numbers of sexual partners, practice of a variety of sexual behaviors, and histories of sexually transmitted diseases.”

Moreover, the SCS’s developer warns that this tool won’t show psychopathology in women:

“Associations between sexual compulsivity scores and other markers of psychopathology showed different patterns for men and women; sexual compulsivity was associated with indexes of psychopathology in men but not in women.“

Furthermore, the SCS includes partner-related questions that Internet-porn addicts might score quite differently compared with sex addicts, given that compulsive porn users often have a far greater appetite for cyber erotica than actual sex.

Like the SCS, the second hypersexuality questionnaire (the CBSOB) has no questions about Internet porn use. It was designed to screen for “hypersexual” subjects, and out-of-control sexual behaviors – not strictly the overuse of sexually explicit materials on the internet.

Another questionnaire the researchers administered is the PCES (Pornography Consumption Effect Scale), which has been called a “psychometric nightmare,” and there’s no reason to believe it can indicate anything about Internet porn addiction or sex addiction.

Thus, the lack of correlation between EEG readings and these questionnaires contributes no support to the study’s conclusions or the author’s claims.

No Pre-Screening: Prause’s subjects were not pre-screened. Valid addiction brain studies screen out individuals with pre-existing conditions (depression, OCD, other addictions, etc.). This is the only way responsible researchers can draw conclusions about addiction. See the Cambridge study for an example of proper screening & methodology.

Prause’s subjects were also not pre-screened for porn addiction. Standard procedure for addiction studies is to screen subjects with an addiction test in order to compare those who test positive for an addiction with those who do not. These researchers did not do this, even though an Internet porn-addiction test exists. Instead, researchers administered the Sexual Compulsivity Scale after participants were already chosen. As explained, the SCS is not valid for porn addiction or for women.

Use of Generic Porn For Diverse Subjects: Steele et al. admits that its choice of “inadequate” porn may have altered results. Even under ideal conditions, choice of test porn is tricky, as porn users (especially addicts) often escalate through a series of tastes. Many report having little sexual response to porn genres that do not match their porn-du-jour—including genres that they found quite arousing earlier in their porn-watching careers. For example, much of today’s porn is consumed via high-definition videos, and the stills used here may not elicit the same response.

Thus, the use of generic porn can affect results. If a porn enthusiast is anticipating viewing porn, reward circuit activity presumably increases. Yet if the porn turns out to be some boring heterosexual pictures that don’t match his/her current genre or stills instead of high-definition fetish videos, the user may have little or no response, or even aversion. “What was that?”

This is the equivalent of testing the cue reactivity of bunch of food addicts by serving everyone a single food: baked potatoes. If a participant doesn’t happen to like baked potatoes, she must not have a problem with eating too much, right?

A valid addiction “brain study” must: 1) have homogenous subjects and controls, 2) screen out other mental disorders and other addictions, and 3) use validated questionnaires and interviews to assure the subjects are actually porn addicts. Steele et al. did none of these, yet drew vast conclusions and published them widely.

No Control Group, Yet Claims Required One

The researchers did not investigate a control group of non-problem porn users. That didn’t stop the authors from making claims in the media which required a control group comparison. For example:

“If they indeed suffer from hypersexuality, or sexual addiction, their brain response to visual sexual stimuli could be expected be higher, in much the same way that the brains of cocaine addicts have been shown to react to images of the drug in other studies.”

Reporter: “They were shown various erotic images, and their brain activity monitored.”

Prause: “If you think sexual problems are an addiction, we would have expected to see an enhanced response, maybe, to those sexual images. If you think it’s a problem of impulsivity, we would have expected to see decreased responses to those sexual images. And the fact that we didn’t see any of those relationships suggests that there’s not great support for looking at these problem sexual behaviors as an addiction.”

In reality, Steele et al. reported higher P300 readings for porn images than for neutral images. That is claerly an “enhanced response“. Commenting under the Psychology Today interview of Prause, psychology professor John A. Johnson said:

“My mind still boggles at the Prause claim that her subjects’ brains did not respond to sexual images like drug addicts’ brains respond to their drug, given that she reports higher P300 readings for the sexual images. Just like addicts who show P300 spikes when presented with their drug of choice. How could she draw a conclusion that is the opposite of the actual results? I think it could be do to her preconceptions–what she expected to find.”

In short, what Prause boldly proclaimed in her many media interviews is not backed up by the results. Another claim from the interview that required a control group:

Mustanski: What was the purpose of the study?

Prause: Our study tested whether people who report such problems look like other addicts from their brain responses to sexual images. Studies of drug addictions, such as cocaine, have shown a consistent pattern of brain response to images of the drug of abuse, so we predicted that we should see the same pattern in people who report problems with sex if it was, in fact, an addiction.

Prause’s reply to Mustanski indicates that her study was designed to see if the brain response to sexual images for people reporting problems with sex was similar to the brain response of drug users when they encounter images of the drug to which they are addicted.

A reading of the cocaine study she cites (Dunning, et al., 2011), however, indicates that the design of Steele et al. was quite different from the Dunning study, and that Steele et al. did not even look for the kind of brain responses recorded in the Dunning study.

The Dunning study used three groups: 27 abstinent cocaine users, 28 current cocaine users, and 29 non-using control subjects. Steele et al. used only one sample of persons: those who reported problems regulating their viewing of sexual images. Whereas the Dunning study was able to compare the responses of cocaine addicts to healthy

controls, the Prause study did not compare the responses of the troubled sample with a control group.

There are more differences. The Dunning study measured several different event-related potentials (ERPs) in the brain, because previous research had indicated important differences in the psychological processes reflected in the ERPs. The Dunning study separately measured early posterior negativity (EPN), thought to reflect early selective attention, and late positive potential (LPP), thought to reflect further processing of motivationally significant material. The Dunning study further distinguished the early

component of LPP, thought to represent initial attention capture, from the later component of LPP, thought to reflect sustained processing. Distinguishing these different ERPs is important because differences among the abstinent addicts, current users, and non-using controls depended on which ERP was being assessed.

In contrast, Steele et al. looked only at the ERP called P300, which Dunning compares to the early window of LPP. By their own admission, Prause and her colleagues report that this might not have been the best strategy:

“Another possibility is that the P300 is not the best place to identify relationships with sexually motivating stimuli. The slightly later LPP appears more strongly linked to motivation.“

The upshot is that Steele et al. did not in fact examine whether the brain responses of sexually troubled individuals “showed the same pattern” as the responses of addicts. They did not use the same ERP variables used in the cocaine study and they did not use an abstinent group and a control group, so they should not have compared their results to the Dunning study claiming the comparison was “apples to apples.”

EEG Technology Limitations

Finally, EEG technology cannot measure the results the researchers claim it can. Although the researchers insist that, “Neural responsivity to sexual stimuli in a sample of hypersexuals could differentiate these two competing explanations of symptoms [evidence of addiction versus high sexual desire],” in fact it’s unlikely that EEGs can do this at all. Although EEG technology has been around for 100 years, debate continues as to what actually causes brain waves, or what specific EEG readings really signify. As a consequence, experimental results may be interpreted in a variety of ways. See Brainwashed: The Seductive Appeal of Mindless Neuroscience for a discussion of how EEGs can be misused to draw unfounded conclusions.

EEGs measure electrical activity on the outside of the skull, and addiction researchers who use EEGs look for very narrow signals of specific aspects of addiction. For example, this recent EEG study on Internet addicts shows how accomplished Internet-addiction neuroscientists conduct such experiments. Note that researchers isolate narrow aspects of the brain’s activity, such as impulsivity, and avoid overly broad claims of the type made here by SPAN Lab. Also note the control group and pre-screening for addiction, both of which are absent in this SPAN Lab effort.

Perhaps the authors are unaware of the technology’s inability to distinguish among overlapping cognitive processes:

“The P300 [EEG measurement] is well known and often used to measure neural reactivity to emotional, sometimes sexual, visual stimuli. A drawback to indexing a large, slow ERP component is the inherent nature of overlapping cognitive processes that underlie such a component. In the current report, the P300 could be, and most-likely is, indexing multiple ongoing cognitive processes.”

Never mind that, by their own admission, P300 might not be the best choice for an ERP study of this type. Never mind that conducting statistical analyses with difference scores has been recognized as problematic for over 50 years, such that now alternatives to difference scores are usually used (see http://public.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/faculty/edwardsj/Edwards2001b.pdf). Never mind that we do not really know what the amplitude of P300 to particular images relative to neutral images really signifies. P300 involves attention to emotionally significant information, but as Prause and her colleagues admit, they couldn’t predict whether P300 in response to sexual images would be especially elevated for people with high sexual desire (because they experience strong emotions to sexual situations) or whether the P300 would be especially flat (because they were habituated to sexual imagery).

Nor could they delineate between greater attention (higher P300) caused by sexual arousal, or greater attention caused by strong negative emotions, such as disgust. Nor can EEG technology delineate between a higher P300 reading arising from sexual arousal versus shock/surprise. Nor can EEG technology tell us if the brain’s reward circuitry was activated or not.

There is a more fundamental problem here: Steele et al. seems to want to take an either/or approach the viewing of sexual images—that EEG responses are either due to sexual desire or to an addictive problem – as if desire can be separated completely from addictive problems. Would anyone suggest that EEG responses in alcoholics or cocaine addicts might be due either entirely to their desire for the addictive substance or to their addictive problem?

Other factors can influence EEG readings. What if an image is related to a genre you like, but the pornstar reminds you of a person you dislike/fear/don’t care to see naked. Your brain will have conflicting associations for such erotica. These conflicts may well be more likely in the case of porn images than in the case of, say, cocaine visuals of powder and noses (used when testing cocaine addicts).

The point is that multiple associations with a stimulus as complex as sexuality could easily skew EEG readings.

Also, Steele et al. assumed higher EEG averages indicate higher sexual arousal, but subjects’ EEG averages were in fact all over the map. Is this because some of them were addicts and others not? Or watching porn that turned them off. Many factors can affect P300 readings. Consider the following, from another P300 study:

Although the functional significance of P300 is still debated1, 2, its amplitude indexes the allocation of resources for the evaluation of stimuli….Reduced P300 amplitude has been reported in many psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia4, depression5, and alcoholism6.

In short, the author’s hypothesis that brains of addicts will show either evidence of addiction or evidence of “high sexual desire” is uninformed. Yet the abstract creates in the reader the impression that the study’s results will show us that these hypersexuals either exhibited (1) evidence of addiction or (2) a positive correlation with “high sexual desire.” And the study’s title then misleadingly proclaims “sexual desire” the winner.

Cues confounded with addictive behavior

Another problem with the study’s design is that SPAN Lab confuses addiction-related cues with addiction itself (behavior). In this study, the researchers claim that watching porn is a cue, not unlike an alcoholic viewing a picture of a vodka bottle, and that masturbation is the addictive activity. This is incorrect.

Watching porn, which is what researchers asked these subjects to do, is the addictive activity for an Internet porn addict. Many users watch even when masturbation isn’t an option (e.g., while riding the bus, on library computers, at work, in waiting rooms, etc.). Viewing porn for stimulation is their uncontrolled behavior.

In contrast, true cues for porn addicts would be such things as seeing bookmarks of their favorite porn sites, hearing a word or seeing an image that reminds them of their favorite porn fetish or porn star, private access to highspeed Internet, and so forth. To be sure, seeing a visual that signals a fetish might serve as a cue for someone with an addiction to that genre of fetish porn, but here researchers used generic porn, not porn tailored to subjects’ individual tastes.

The assumption that this study is “just like” drug studies, is one of the many shaky assumptions Steele et al. makes Keep in mind that a picture of a blackjack table is not gambling; a picture of a bowl of ice cream is not eating. Viewing porn, in contrast, is the addictive activity. No one has any idea what EEG readings should be for porn addicts engaging in their addictive activity.

By discussing their results in light of genuine cue research relating to other addictions, the researchers imply that they are comparing “apples to apples.” They are not. First, the other addiction studies Steele et al. cites involve chemical addictions. Porn addiction is not as easy to test in the lab for reasons already explained. Second, the design of Steele et al. is entirely different from those studies it cites (no control groups, etc.).

Future studies on cue-reactivity to sexual images or explicit films must be very cautious in their interpretation of the results. For example a diminished brain response could indicate desensitization or habituation, rather than “not being addicted”.

Conclusion

First, one can make a strong argument that this study should have never been published. Its diversity of subjects, questionnaires incapable of assessing internet porn addiction, lack of screening for co-morbidities, and absence of control group resulted in unreliable results.

Second, the solitary correlation – less desire for partnered sex correlating with higher P300 – indicates that more porn use leads to greater cue-reactivity (cravings for porn), yet less desire to have sex with a real person. Put simply: Subjects using more porn craved porn, but their desire for real sex was lower than in those who viewed less. Not exactly what the headlines stated or the authors claimed in the media (that more porn use was correlated with higher desire “sexual desire”).

Third, the “physiological” finding of higher P300 when exposed to porn indicates sensitization (hyper-reactivity to porn), which is an addiction process.

Finally, we have the authors making claims to the media that are light years away from the data. From the headlines, it’s clearly journalists bought the spin. This points to the bleak state of science journalism. Science bloggers and news outlets simply repeated what they were fed. No one in the media read the study, checked the facts, or asked for an educated second opinion from actual addiction neuroscientists. If you want to promote a certain agenda, all you need to do is concoct a clever press release. It matters not what your study actually found, or that your flawed methodology may only produce a jumbled data salad.

Also see these critiques of the same study:

- Misinformed Media Touts Bogus Sex Addiction Study, by Robert Weiss, LCSW & Stefanie Carnes PhD

- “Don’t Call it Hypersexuality: Why we Need the Term Sex Addiction,” By Linda Hatch, PhD

Similar to Steele et al, a second SPAN Lab study from 2013 found significant differences between controls and “porn addicts” – “No Evidence of Emotion Dysregulation in “Hypersexuals” Reporting Their Emotions to a Sexual Film (2013).” As explained in this critique, the title hides the actual findings. In fact, “porn addicts” had less emotional response when compared to controls. This is not surprising as many porn addicts report numbed feelings and emotions. The authors justified the title by saying they expected “greater emotional response”, yet provided no citation for this dubious “expectation.” A more accurate title would have been: “Subjects who have difficulty controlling their porn use show less emotional response to sexual films“. They were desensitized

See Questionable & Misleading Studies for highly publicized papers that are not what they claim to be.